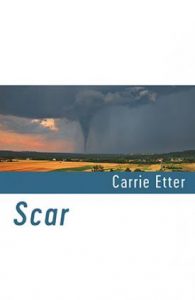

Scar

In a turbulent political world, where the current US administration’s denial of climate change is clear, UK-based Illinois poet Carrie Etter’s Scar seems profoundly relevant. Informed by former government climate change reports, conversations with the Met Office and interviews with her fellow Illinoisans, this single long poem explores the impact that global warming is wreaking on her home state.

In a turbulent political world, where the current US administration’s denial of climate change is clear, UK-based Illinois poet Carrie Etter’s Scar seems profoundly relevant. Informed by former government climate change reports, conversations with the Met Office and interviews with her fellow Illinoisans, this single long poem explores the impact that global warming is wreaking on her home state.

Etter pulls no punches from the opening lines on:

at my beginning: prairie at my beginning: a town called normal on the far horizon cornfield upon cornfield splayed flattened by tornado [.]

The poet also questions the likely fate of those affected based on class divides, hinting at the expendability of some but not others:

more tornadoes and if you haven’t a basement or cellar? who hasn’t a basement or cellar? apartment-, trailer-home dwellers yeah, you know [.]

The line breaks, the fragmented, panicked lineation and the punctuation in lines alluding to basement, cellars and trailer-home dwellers, show clear class distinctions. The strong horizontals in the layout and the use of whitespace are in themselves a salute to the state’s flat and fragile topography in the face of these storms. A few lines on, in a strongly urban setting, she develops her social commentary, reminding us of the contrasting tapestry of this landscape.

A number of technical references occur. For example…a “heat island” is an urban or metropolitan area which retains and emits more heat due to the modification of the land, population numbers and subsequent human activity. Her frequent use of the term forces her reader to really consider that phrase. Again, the writer questions herself and us: “

and who lives there?” Etter sweeps us easily between urban nightmares and her image-rich descriptions of rural life:

In Illinois, I am the cicada gnawing through summer nights [.]

The poet conjures visions of a colourful panorama, teeming with wildlife, just enough to allow us to fall a little in love with the land. The scene cuts sharply to blizzards and a snapshot of childhood memory, demonstrating how terrifyingly extreme the state’s weather can be. Her father is depicted desperately calling out over a CB radio to her mother, flicking between their usual and emergency channels, whilst she holds her breath, realising her mother may be lost in the blizzard.

Etter drags us from this memory and back to the wildlife of Illinois, the calm of the trees. We are permitted an aerial view here as we survey the immensity of the forests, sand prairies, rocky outcrops and wetlands with their abundance of indigenous animals. The statement on the page opposite these idyllic descriptions makes no bones about the writer’s view on the destruction of her land: “The apologies shine like coins in the bowels of a fountain – ”

In Scar, she paints natural scenes alongside stark images of school children practicing tornado drills, the scream of sirens piercing their childhood with monthly regularity. When the blizzards return, Etter slaps the reader in the face with grave consequences:

blizzards come again and a helicopter – with such snow, such winds – cannot deliver the heart in time[.]

Scar finishes as it began, packing a punch. The final stanza gives us plenty to consider on more than one level:

(it’s true: I bark and coo, swim and wriggle flutter and slide, snort and screech am animal amid animals – and I annihilate. I, the world’s curse.)

Etter suggests that despite officialdom’s way of making loud noises, climate change is still an issue that will not go away. Using ‘I’ suggests that the writer, a human with her own carbon footprint, also feels responsible.

There is a richness here, which is both political and deeply personal. The writer’s affection and concern for her homeland and its inhabitants is clear throughout. If Etter’s hope was to have her poem raise the profile of this cause, then we can declare Scar a mission accomplished.

Leave a Reply