Kei Miller in conversation with Susan Mains

This is an edited transcript; the video of the complete interview can be accessed by clicking the above image. A review of The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion is available HERE.

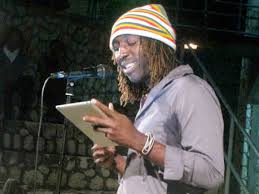

Susan Mains: Welcome to our conversation today with Kei Miller who is visiting us here at Dundee as part of the Dundee Literature Festival, and has been reading from his recent work, The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion. We thought we would just have a short conversation today to talk a bit more about the work and learn more about the process of putting the pieces together. I don’t know if you’d like to start with a particular poem from the collection?

Kei Miller: Yes, sure. Why don’t I just start with the very first poem because the concept of “heartbless” is important. “Groundation” is how Rastafarians in Jamaica celebrate Selassie’s first visit – “grounation” or “groundation” [Miller reads “Groundation”].

Kei Miller: Yes, sure. Why don’t I just start with the very first poem because the concept of “heartbless” is important. “Groundation” is how Rastafarians in Jamaica celebrate Selassie’s first visit – “grounation” or “groundation” [Miller reads “Groundation”].

SM: Thanks very much, Kei. I think the words were really evocative in many ways – a real connection to place. I wondered if you could talk about… communicating a particular sense of the local landscape with lots of emotive details, with obviously bigger themes around knowledge and mapping, and how do you bring those things together?

Kei Miller: I don’t know whether I am so conscious of those things. As a writer, there are things that you learn to do: in order to be universal, one ought to be specific, and in order to give a sense of something wider, one should look narrow. That’s just about the power of description; that’s just about relishing the complexity of the thing that you’re looking at. The politics of the local versus the global are very important to me but I don’t think in the process of writing it, I’m as conscious. I think in the process of writing, I’m looking for the most telling detail and that’s a writerly gravitation that comes over.

SM: So, for instance, particular words evoke a particular image or ideas?

Kei Miller: Sometimes a particular word, but sometimes it’s the image. I think a writer should always show people things that they’ve probably seen but they weren’t aware that they saw it before. You’re always looking for that image, or how to house a thing that always happens in new words… [for example,] it’s evening falling in Jamaica, which can be a very violent place and but… thinking about the birds that are always on the overhead wires … There is a line there [about]… how birds and bullets pack the purple band of evening and sing the sky to black, I think all Jamaicans, in a way, know that image. But I think I’m always feverishly trying to find those new ways to say what we know already.

SM: It’s interesting you say that because earlier you were talking about how you write collections. In this case, it’s a conversation that kind of runs throughout this collection. And I wondered if you could also talk a bit about that – about the role of the conversation in trying to tease out the problems of cartography and the way it’s been used.

Kei Miller: One of the things I was saying as well was… I thought of cartography as discursive…. I  didn’t think of cartography as always representing… different elements of dialogue and voice that you recognise. Cartography always has a viewpoint. It always has a bias. It always has limits. It always has an objective. All these things are what I associate with voice, with narrative. I realise that cartography always had those things. And so it seemed… [natural to]… suggest that it [cartography] was dialogic… I thought how places are named and renamed in Jamaica, and how that represents a different people participating in the cartography of the land and sometimes contesting an imposed history… [for example] the stately home Chateau Vert, which the people cannot hear, and which they rename as Shatover. And in renaming… they manage to re-insert an element of history that might have been forgotten. And the cartographer seems participative, dialogic, complex and that’s kind of what I wanted to bring out. Or one of the things I wanted to bring out in this collection….

didn’t think of cartography as always representing… different elements of dialogue and voice that you recognise. Cartography always has a viewpoint. It always has a bias. It always has limits. It always has an objective. All these things are what I associate with voice, with narrative. I realise that cartography always had those things. And so it seemed… [natural to]… suggest that it [cartography] was dialogic… I thought how places are named and renamed in Jamaica, and how that represents a different people participating in the cartography of the land and sometimes contesting an imposed history… [for example] the stately home Chateau Vert, which the people cannot hear, and which they rename as Shatover. And in renaming… they manage to re-insert an element of history that might have been forgotten. And the cartographer seems participative, dialogic, complex and that’s kind of what I wanted to bring out. Or one of the things I wanted to bring out in this collection….

SM: … We view mapping in different ways, [ we challenge] … traditional views of what mapping is; it makes me think a wee bit of that Anansi figure that you allude to in some of your work… could the cartographer be seen as an Anansi figure? If we start to see cartography as being more inclusive… where it becomes part of these other stories that have been hidden in landscapes, do we have an Anansi cartography do you think?

Kei Miller: You know, I was actually thinking recently that I think my next poetry collection might be called Anansi but… in a way, yes, absolutely. In the way of cartography being a tricksy enterprise and so obviously the tricksy enterprise ought to be done by the Trickster…. One of Anansi’s most famous acts is when he tries to own all the stories, which is exactly what the cartographer tries to do. He tries to colonise all the stories of a landscape and he who holds the stories has the power. So, yes, in a way, I guess I could see the act of cartography as an act of Anansi-ism. That makes complete sense to me.

SM: I quite like that idea as well… the hidden story, you’re trying to lead people down another path. Earlier you were saying that thing of having two voices which seem in tension: whether it’s the Cartographer and the Rastaman, and… the Warner Woman and the narrator… people presume that you’re maybe one character when really you’re the other one, right?

SM: I quite like that idea as well… the hidden story, you’re trying to lead people down another path. Earlier you were saying that thing of having two voices which seem in tension: whether it’s the Cartographer and the Rastaman, and… the Warner Woman and the narrator… people presume that you’re maybe one character when really you’re the other one, right?

Kei Miller: Yes, it’s [about] constantly weaving webs – sometimes webs of deception. But I mean the other great thing about Anansi is that he’s such a… cross-dresser… wearing different faces and using different voices and, you know, continually masking and unmasking….

SM: We were also talking [earlier]… about how you find voices… working through different ideas. I was quite curious – you write across a lot of different genres: poetry, short stories, long fiction, non-fiction…. [Do the different formats] give you the opportunity to express particular ideas or different themes… of finding a different voice and different settings?

Kei Miller: Yes… not everything I want to write is suited or can be shaped into every genre [but]… I think it does offer me a kind of flexibility. There’s a part of blogging that is, to me, the most immediate connection I have with a book, sometimes with Jamaica in particular, with what’s happening; I don’t want to wait four years for a book to come out to say that what that MP said was stupid… and [that] it ought to be challenged now. Poetry gives you the possibility of language. The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion… could have been a series of essays but I think that’s been done and so I wanted to do something different. And at the end of the day I think that what poetry offers is that it re-makes language. At the end of the day, there are many ideas [in it]… Though it [also] seems to be competing to be a book of essays… what made me sure that it was a poetry collection is that weird dissonance that happens when the very spiritual language of Rastafaria encounters the very scientific language of cartography. How do they make a sound against each other which would, in my mind, clearly be a new sound? … Poetry offers that possibility, I think, in a way that other genres don’t offer that possibility. There’s something I could do with this as a poetry collection that I couldn’t do with it as an essay. So there are various impulses. The impulse to speak truth to power, the impulse to do something new with language… the impulse to tell a good story. If there was a story I wanted to tell, it wouldn’t even be a sequence of poems. This [The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion] pretends as well to be narrative but there’s no real plot. But there are stories I want to tell. Definitely; I mean, separately, those would never be essays or poems. So, yes, so working through different genres does give me the opportunity to do different things that I want to do.

SM: … What was it that acted as a catalyst for you in your early days of writing to get you into that  area?

area?

Kei Miller: The fact that I was horrible at everything else. I really envy writers who are good at other things. Actually, I don’t think I’m a bad teacher now. I think writing has forced me to be a teacher. And I really like being in the academy. That’s something… it feeds me in profound ways…. there was a scary period where I thought, “Well, what am I going to do with my life?” … And for me, if I had a choice, I wouldn’t have focussed on writing. Someone said when I was at Uni a long time ago, I can’t remember his name. It’s a West Indian playwright who’s since died, but he said, he came to a session and he said, “Take this with all the insults you want, but a career in the Arts is something you should only do if you can’t do anything else.” And it was the most freeing thing I’d ever heard because I thought that’s why I’m going to be a writer. Not because I have a choice but because I can’t do anything else. And it’s very liberating….

SM: But then done so well at this. It’s great with the Forward Prize and everything. It’s brilliant!

Kei Miller: The most shocking year…

SM: Is there anything about being in Jamaica, when you were growing up in Jamaica, at all, that you think may have kind of spurred on some of these stories or kind of acted as a catalyst?

Kei Miller: Well, the connection between Jamaica isn’t ever so far… I go back probably three times a year and so, the connection doesn’t feel broken. It doesn’t feel interrupted… Jamaica is somewhere where I do a lot of thinking, I spend a lot of time with my friends there, where my godchildren are. I was in a conversation with some friends the other day in Jamaica. They said something about “your students in Glasgow” at the time and somebody at the table said, “What? You live in Glasgow?” And we’d hung out several times and it’s the first time she found out that I didn’t actually live [in Jamaica]… which is what I want. But the point is, does Jamaica feed my writing, my imagination, the impulse to write the kind of stories I write? Absolutely. But it’s not a Jamaica that belongs to my childhood. It’s a Jamaica that’s present and referring right now….I don’t believe in getting distance from a place in order to write it. The place has to be in your face…. For me, that’s a connection I need…. I used to be an academic at Glasgow Uni. And the conversations that you [might be]… [would be] slightly different [to]… the conversations you’re having at Uni in Jamaica… To be a part of interesting, new conversations that you were not a part of before and to get excited by these things, to have experts in different fields who get very fired up, so to live in that world, the world of the academy, the world of thought where people really are excited about the new ideas, the new theory… to be a part of a periphery and to have those kinds of conversations in earshot… So those are the two impulses. It’s the local of Jamaica, but [also] a kind of international space of thought that I’m trying to put together.

SM: With that on-going connection. What’s the response been there in terms of the work coming out and what’s it like doing the readings of your new work…

Kei Miller: in Jamaica.. I’m going back in December to launch the last two books. But the response in Jamaica has been incredible… Absolutely incredible. I’m writing at the same time as another Jamaican writer who is just obviously the most amazing novelist…. Marlon James. Marion was in London the other day and we were laughing about this because… I mean Marlon is a better novelist than I am and it’s not even close. But we were kind of laughing about [the feeling that] somehow Jamaica seems to have embraced me a little bit more. And Marlon said, “They clearly haven’t read your work carefully enough”. They think that Marion is levying a kind of harder critique than I am. We’re writing about very similar things, and I think in very similar ways; but Marion’s much more unflinching than I am. But it means there’s been a massive embracing of what I’ve been doing there.

SM: … Do you have a sense that there is sort of a camaraderie among Caribbean writers who are exploring similar themes perhaps in different ways?

Kei Miller: A lot of us. Yeah. Definitely. Those are friendships I value a lot because they are doing absolutely interesting things [and] in very interesting ways.

SM: It sounds great. I wondered if I could maybe ask you to read another piece from your collection?

Kei Miller: Yes. I’ll read something very dark. Again at the beginning. And it’s just that when Europe first came across the Caribbean, they tell this narrative that they must have come across Paradise, which is another kind of revisioning which isn’t very true. So I started to write this poem early on in the collection about the land before it’s mapped. It’s called: “Unsettled” [Miller reads “Unsettled”].

SM: Thanks very much. It seems like such a poignant moment, actually, to finish up, when there’s so many things that are unmapped actually. I think you point in the direction towards some really exciting future journeys in your work as well.

Kei Miller: Thank you, Susan….

[…] Mains, S. (s/f). https://dura-dundee.org.uk. Recuperado el 10 de 05 de 2019, de https://dura-dundee.org.uk/2014/11/09/kei-miller-in-conversation-with-susan-mains/ […]