Robert Mapplethorpe: Artists Rooms

Since Robert Mapplethorpe emerged in the 1970s his work has been regarded as synonymous with controversy. The artist’s explicit critique of societal norms and the unconventional beauty of some of his photographs have augmented this controversial reputation. Having been regarded as a pioneer of artistic explorations of sexuality and gender, we find Mapplethorpe continuously cited as an exemplar of a questionable aesthetic. I can thus be forgiven therefore for expecting an uncomfortable or somewhat voyeuristic experience. However this exhibition provided something else altogether.

Since Robert Mapplethorpe emerged in the 1970s his work has been regarded as synonymous with controversy. The artist’s explicit critique of societal norms and the unconventional beauty of some of his photographs have augmented this controversial reputation. Having been regarded as a pioneer of artistic explorations of sexuality and gender, we find Mapplethorpe continuously cited as an exemplar of a questionable aesthetic. I can thus be forgiven therefore for expecting an uncomfortable or somewhat voyeuristic experience. However this exhibition provided something else altogether.

After passing the “No Photography” sign on entry to the gallery, we are immediately confronted with the organ that determined Mapplethorpe’s career.  Self-portrait (1989) captures only his eyes, and is a very apt start to an exhibition that showcases his vision of the world. This “Artist Rooms” collection fills two galleries painted in Mapplethorpe’s favourite colour purple, with black and white photography depicting close friends, celebrities, children, flowers and – most poignantly -Mapplethorpe himself. It shows a wide range of works that highlight his astute understanding of formal light and meticulous approach to composition, in his iconic, intimate and revealing style.

Self-portrait (1989) captures only his eyes, and is a very apt start to an exhibition that showcases his vision of the world. This “Artist Rooms” collection fills two galleries painted in Mapplethorpe’s favourite colour purple, with black and white photography depicting close friends, celebrities, children, flowers and – most poignantly -Mapplethorpe himself. It shows a wide range of works that highlight his astute understanding of formal light and meticulous approach to composition, in his iconic, intimate and revealing style.

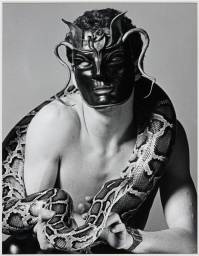

Mapplethorpe cultivated an intimate style in his portraiture that led to the more scandalous images he is best known for today—a realisation that this exhibition reverses. This show successfully places Mapplethorpe’s occasional, yet more familiar controversial works, within the broader context of his practice, allowing us to appreciate those images for their more traditional beauty—shockingly un-shocking. World Women’s Body Building Champion, Lisa Lyon (1982) —posed so as to echo the crucifixion and accentuate the androgyny of her body—is recontextualised by its juxtaposition beside a portrait of Arnold Schwarzenegger, cushioning the subject’s impact.

The exhibition also includes photographs of children Mapplethorpe’s used as symbols of hope and innocence, whilst at the same time counterpointing his imminent death. Never scared to confront the issue of mortality, his Self-portrait (1989) stares into the camera as if into the face of death itself. This work absorbs the spotlight with its dominant central position in the exhibition and the vast black background, contrasting with his virtually disembodied floating head, slightly out of focus in relation to the skull clenched in his hand. This was taken, portentously, just a few months before Mapplethorpe died of Aids in 1989. An earlier portrait of fellow photographer John McKendry is unusually cropped so as to allow the viewer to see only half of his face, focusing on what comes over as his discerning-looking eye adjacent to an ominous plug on the wall; Mapplethorpe was only too aware that McKendry was close to death (he passed away the next day).

Mapplethorpe’s documentation of friends and peers entices us towards less familiar faces, rather than celebrities. As a generation of “camera-phone-ers” and “face-bookers”, we are accustomed to seeing the world through the photograph as never before. Today, even the most personal encounter can be pre-empted through photography’s image-making. Like it or not, it is increasingly likely that we will be first introduced to new people, even friends’ children, through a camera rather than in person. Mapplethorpe’s photographs involving the New York S&M scene may have been voyeuristic in the past, but in our Internet age we are becoming inured to such exposure. Whilst Mapplethorpe consciously takes on roles in his self-portraiture to shape and preserve public perception, we subconsciously echo this trait ourselves in our own selection of images to share with others today, predominantly through social media.

This Artists Rooms exhibition offers a conscious and intimate documentation of image-making and reminds us how depersonalised the everyday documentationof our lives has become through our use of photography. These images – in stark contrast to those referred to by the “No-Photography” sign in the doorway – teach us about our own increasingly apathetic experience of photography in contemporary society today.

Daniel Shay

Leave a Reply