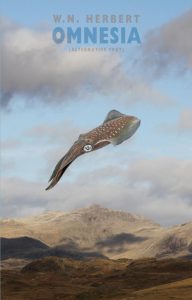

Omnesia (Remix) and Omnesia (Alternative Text)

The spirit of Edwin Morgan is at large in Bill Herbert. But Herbert’s new double collection also belongs in the tradition initiated by Wordsworth’s Prelude, in that it exhibits the poetic mind contemplating itself. As in the great Romantic poem, which remained unfinished, there is a sense in which Herbert’s two books of specular poetry, despite the ways in which they loop in on themselves, likewise represent an open-endedness. This seems appropriate, given the (probably definitive) questing nature of poetic sensibility, which is forever seeking the right form for its subject. Herbert has previously described himself as a polystylist; and he has that chameleon habit of vanishing into his many forms, which is also a Shakespearean trait (“many-minded”, as Coleridge had it). He seems reminiscent of Auden, who never tired of experiment with received and not-so-received forms. But whereas Auden once said he had to know a great deal before he could feel anything (in effect, an aspiration to a kind of customised omniscience), Herbert wishes to empty himself of, and to ironise, this impulse to knowledge, stylistic or otherwise, by hybridising it with a needful forgetfulness. He makes poems, here, which forget (or half-recall) where they’ve been, what they knew, how they behaved, where they arrived. The overall effect is ludic, enriching and celebratory. A playful, and itself fertile, dalliance with poetic fertility results.

The spirit of Edwin Morgan is at large in Bill Herbert. But Herbert’s new double collection also belongs in the tradition initiated by Wordsworth’s Prelude, in that it exhibits the poetic mind contemplating itself. As in the great Romantic poem, which remained unfinished, there is a sense in which Herbert’s two books of specular poetry, despite the ways in which they loop in on themselves, likewise represent an open-endedness. This seems appropriate, given the (probably definitive) questing nature of poetic sensibility, which is forever seeking the right form for its subject. Herbert has previously described himself as a polystylist; and he has that chameleon habit of vanishing into his many forms, which is also a Shakespearean trait (“many-minded”, as Coleridge had it). He seems reminiscent of Auden, who never tired of experiment with received and not-so-received forms. But whereas Auden once said he had to know a great deal before he could feel anything (in effect, an aspiration to a kind of customised omniscience), Herbert wishes to empty himself of, and to ironise, this impulse to knowledge, stylistic or otherwise, by hybridising it with a needful forgetfulness. He makes poems, here, which forget (or half-recall) where they’ve been, what they knew, how they behaved, where they arrived. The overall effect is ludic, enriching and celebratory. A playful, and itself fertile, dalliance with poetic fertility results.

That poetic procedures like Herbert’s have a notional grounding in the way things are – that is to say, in the nature of physical reality – is brought to mind when reading a recent New Scientist’s cover story. It reminds us that a half-silvered mirror will allow a single photon both to pass through and, simultaneously, to be reflected back to an onlooker. What’s more, quantum entanglement means that even widely separated particles, with no apparent means of communication, mirror each other’s energy and spin. There seems to be, in other words, some physical apparatus deeper and more influential than even matter’s most fundamental energetic states – more basic still than the (now under exploration) internal structuring of quarks and electrons, previously assumed to be structureless. By happy accident, or, if free will is a casualty of our physical theories, by fate, Herbert’s mirrorbooks mimic and reproduce the symptomatic ground behaviour of matter and energy.

Yet for all the carnivalesque, freewheeling exuberance of this celebration of the spirit of poetry; for all its formal rejoicing in disorientation, its endless pilgrimage of invention, its restless pursuit of comprehension, structural experiment is not necessarily much more than an epiphenomenon which just happens to be very much in your face. The poetic pleasures as such (they’re considerable) turn out to be reassuringly traditional. “Sometimes you’re slid beneath the lid / of sleep as though below the ice / that locks the river and you see / it’s like a thousand layers of / old paper: wrapping paper like / a mulch of stars, old newsprint in / too many scripts, and letters / in half-recognised, half-strangers’ hands / like decades of wallpaper / but without the wall –” (“Hotel Bessonitsa”). Handling of thought, feeling, rhythm and image here are, to coin a phrase, expectedly unexpected: this is what poetry “should” achieve. Similarly in ‘Hotel Vojvodina’, the procedures are received and familiar from long use: “I watched myself attempt to sleep, / head and body in one sheet; / night filled a pit with shutting bars / where still, till two, they played guitars.” Indeed, throughout these twinned volumes, examples abound of popular wit, established modes, forms, and rhyming patterns, so that there is much to enjoy even for any reader not particularly drawn to avant-garde writing. Herbert, in all his wanderlust, never touches down anywhere for very long. The mayfly sensibility lives and dies, takes off and visits; but it doesn’t live anywhere, though it breeds.

Jim Stewart

Leave a Reply