Division Street

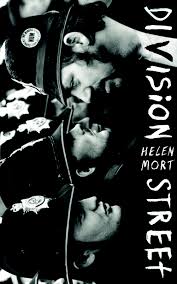

The cover of Helen Mort’s debut collection consists of a photograph of a miner confronting policemen during the 1984 Strike; Division Street promises a work “marked by distance and division”, “[f]rom the clash between striking miners and police to the delicate conflicts in personal relationships”. The title itself announces this. Outwardly then, the book indicates an enclosure of poetry concerned with social and political conflict; more specifically, that of the Miners’ Strike, referenced in the opening lines of “Scab”, printed on the cover:

The cover of Helen Mort’s debut collection consists of a photograph of a miner confronting policemen during the 1984 Strike; Division Street promises a work “marked by distance and division”, “[f]rom the clash between striking miners and police to the delicate conflicts in personal relationships”. The title itself announces this. Outwardly then, the book indicates an enclosure of poetry concerned with social and political conflict; more specifically, that of the Miners’ Strike, referenced in the opening lines of “Scab”, printed on the cover:

A stone is lobbed in ’84,

hangs like a star over Orgreave.

Welcome to Sheffield. Border-land,

our town of miracles – […]

Yet the cover of Mort’s collection misrepresents and completely underestimates her work.

Unquestionably, “Scab” addresses that 1984 industrial action. Yet, whilst other poems do offer subtle references – “[…] a man was felled by bricks / in the strike.” (“Twenty-Two Words for Snow”) – “Scab” is the only poem to address the strike openly. Interestingly, considering the status given to this poem, it is also the collection’s most criticised piece. The Observer’s Kate Kellaway deems it the most “[a]mbitious but least convincing”, arguing that “Scab” “feels willed and riskily inauthentic.” The authenticity of the poem may not be immediately convincing; in a recent interview, Mort expressed her own initial apprehension, rooted in her feeling that “as someone who was hardly born at the time of the strike, I felt in some ways I wasn’t qualified to say anything about it”.

However, Mort deserves to be credited for her honesty. Mort does not feign authenticity and the reader is well-advised to disregard Division Street’s flawed marketing. Mort’s primary concern is not the strike itself and Division Street is not simple political verse. Rather, as the poem asserts, “This is a re-enactment.” The value of “Scab” lies not in its account of the strike but in the poet’s connecting it to her own experiences at Cambridge University:

One day, it crashes through

your windowpane; the stone,

the word, the fallen star. You’re left

to guess which picket line

you crossed – a gilded College gate,

Division Street witnesses Mort’s guilt as she crosses the invisible picket line of the “gilded College gate”, betraying her Northern hometown, and it is in the poetic expression of pertinent, personal and profound emotion, that “Scab” really succeeds.

With “The Complete Works of Anonymous”, an overtly metapoetic piece, Mort composes a portrait of her ideal poet, one whose anonymity speaks to the power of the verse to stand alone:

I’ll raise a glass to dear Anonymous: the old

familiar anti-signature, the simple courage

of that mark. I wish that each of us

could put such trust in words we’d spend a lifetime

on the vessel of a single verse, proofing our lines,

only to unmoor them from our names.

Mort’s own poetry certainly qualifies for such accolades! She works mostly with traditional lyric poetry – her use of meter and rhyme impeccable, her rhythms beautifully executed. Notwithstanding such technical skills, her stylistically unconventional poems also encompass delicate yet commanding rhythms:

At night,

our shadows tanglein their fatal dance.

Death isthe shape

beneath romance

(“End”)

Mort’s poetry achieves a certain memorability, not only through rhythm, but also through her creation of timeless, universal images. “The Year of the Ostrich”, for example, argues for a sign of the Ostrich within the zodiacs:

for surely there must be a sign

for those of us with such unlikely grace,

who hide our heads, or bear the weight

of wings that will not lift us.

It is significant that this is the only debut collection in the Eliot shortlist. This new Derbyshire Laureate deserves to be there, for she writes poetry which will endure the test of time.

Chloe Charalambous

Leave a Reply