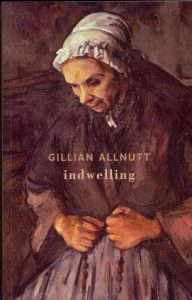

indwelling

indwelling is the sixth collection of poems Gillian Allnutt has produced for Bloodaxe. It is a collection of understated beauty: sparse, yet refined and eloquent, yielding the consistent impression of a quiet voice speaking steadfast words.

indwelling is the sixth collection of poems Gillian Allnutt has produced for Bloodaxe. It is a collection of understated beauty: sparse, yet refined and eloquent, yielding the consistent impression of a quiet voice speaking steadfast words.

The collection divides into three main parts: “Boxted”, “Stoup”, and “Steppe”. “Boxted” begins with a number of delicately descriptive pieces inspired by early twentieth century figurative paintings by artists including Paula Modersohn-Becker, Gwen John and Peter Ilsted. These are poised poems and constitute a striking opening. After this, we move through a series of pieces evoking Allnutt’s family history. Here, as throughout the collection, the gaps between the poems are orchestrated to build subtle dynamics – these are pieces meant to be read and re-read, and to alternate between revelation and concealment: reading “Her Stroke”, “my mother, her brother”, “Mother”, and “the child” as a tetralogy, for example, one feels gently pulled towards past and future, all the while aware that the full impetus behind Allnutt’s narrative thread, implacably there for her, will remain hidden for her reader, at her conscious discretion.

“Stoup” forms a more thematically diverse set, beginning with works focused on place (“Earth”, “Shore”, “her dwelling”, “Asylum”), moving through fleeting childhood memories (“Coronation” and “My Seventeenth-century Girlhood”), then resolving into what are some very sparse poems indeed (“now”, “duduk”). There is, however, a consistent impression of telescoping between times and places: “Earth”, for example , renders the claustrophobic sense of a world pressing in on the shaky sanity of old age, whereas its sister piece, “earth” , evokes youth and its possibilities; these are split moments of the same life, seeking verse to re-communicate across time:

Sanity, a helmet, stops you hearing things.

The lucid talk of stones.

The sea, aloud.

The whole word-

Hoard.

(“Earth”)

“Steppe” begins by situating us in Oxford Botanic Gardens, which it paints vividly, yet with great economy; it then moves to elaborate on classical music (“Shostakovich”, “Sibelius”, “his cello”), before developing a series of wounding reflections on Allnutt’s father, a figure glimpsed as if in silhouette (“To let my father go”, “infather”, “love to burn him down like belsen”). The final poems of this section play a wonderful trick of geographical dislocation, taking us to Armenia, then the Baikal reservoir in Siberia: the general impression rendered is of a scattering to the winds, as Allnutt picks us up and throws us into the open.

Allnutt has been described as a “reticent” poet, and indwelling partly confirms this. Registering at just 71 pages, the collection is intentionally short and imagistic: where it hits the mark (as with “Earth” and “to let my father go”) it is pithy burgeoning on lapidary; where it occasionally misses, it can seem terse or taciturn. On a cursory reading, one might therefore get the unfortunate impression of hermeticism: a sense of language curling in upon itself too tightly.

If indwelling tends in part towards silence, however, the remainder tends towards song. It does so in very particular ways, two of which deserve concluding comment. First, Allnutt develops an enduring sense of place: this reaches a crescendo as we are scattered to the winds of Russia in the final verses, but a bass note is sounded from the beginning, particularly in the acute sense of the east coast of England that Allnutt communicates, from Newcastle to Norfolk. Second, Allnutt makes superb use of other media (such as the paintings and works of composers referred to above); this is so well incorporated as to produce a kind of synaesthesic reverie, as the reader’s imagination works overtime to conjure absent works; it is too well-employed to be a studied trope, and causes the pages to sing too well to allow any suspicion of hermeticism to stand.

Dominic Smith

Leave a Reply