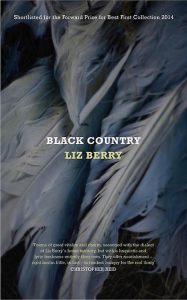

Black Country (Winner of the Forward Prize “Best Debut Collection 2014”)

Liz Berry opens her debut collection, Black Country, with the jubilant line, “When I became a bird, Lord, nothing could not stop me”, and, indeed, she never stops soaring. Themes range from summers of childhood innocence to sex and marriage, all set against Black Country landscapes, history and characters.

Liz Berry opens her debut collection, Black Country, with the jubilant line, “When I became a bird, Lord, nothing could not stop me”, and, indeed, she never stops soaring. Themes range from summers of childhood innocence to sex and marriage, all set against Black Country landscapes, history and characters.

In these dazzling, sensuous, and utterly beguiling poems, Berry reclaims the dialect of her native West Midlands with its bostin fittle (great food), tranklement (bits and bobs) and guttling (chewing). Her use of dialect often connects contemporary concerns with times past in ways subtler than standard English might manage. So, in “Tipton-On-Cut”:

..like Lady Godiva, we’ll trot in on an oss

who’s guttling clover at the edge of the bonk.

We’ll goo straight to the sweet cabbage heart of ‘local’:

shout ‘oiright’ to blokes lugging spuds in their allotments,

yawning in the dark to call centres and factories;

we’ll flirt wi’ Romeos, grooming at Tip’N’Cut,

sunning emselves to creosote fences down the tan shop.

In the dialect poems in particular, there’s an earthiness of language and sound which parallels the down-to-earth lives of previous generations. “Bostin Fittle” opens:

At Nanny’s I ate brains for tea,

mashed with hard-boiled egg,

or trotters, groaty pudding,

faggots minced with kidney and suet.

Dialect words bring an extra dimension, drawing on echoes from standard English. “Jack squalor”, for example, lends an uneasiness to the poem “Birds” which the English equivalent (“swallow”) lacks; “cut” repeatedly brings an extra edge of meaning and feeling which “canal” lacks.

Berry’s collection is a celebration of the Black Country – its language as well as the culture and communities that have forged it. “Homing”, a love poem to a girl’s Black Country dialect, makes this inter-connectedness of dialect and material culture explicit:

bibble, fettle, tay, wum,

vowels ferrous as nails, consonantsyou could lick the coal from.

I wanted to swallow them all: the pits,

railways, factories thunking and clanging

the night shift, the red brick

back-to-back you were born in.

Dialect also adds to the folkloric, timeless qualities of Berry’s poems, many of which are at once tender, charming and dark. In “The Sea of Talk”:

Bab, little wench, dow forget this place,

its babble never caught by ink or bookfer on land, school is singin’ its siren song

and oysters clem their lips upon pearls in the muck…

There’s a musicality to the poetry; her deft use of assonance and alliteration and her frequent inclusion of refrains and lists of wild flowers, names of canals, collieries and canal boats, not only add distinctive rhythms but also make connections with Anglo-Saxon antecedents and reveal a West Midlands specificity in her work. In “Sow”, the libidinous pig is deliciously personified in sound as much as image:

an’ when lads howd out opples on soft city palms

I guttle an’ spit, fer I need a mon

wi’ a body like a trough of tumbly slop

to bury me snout in.

Berry has a wild imagination which melds the everyday with the fantastic in a uniquely innocent yet knowingly unnerving manner. Startling themes and titles are a feature of her work -“The Year We Married Birds”, “The Last Lady Ratcatcher” and “Our Lady of the Hairdressers”, for example. And opening lines such as, “Let me tell you about the sex I knew/before sex” (“The Silver Birch”) and “I was a boy every weekday afternoon” (“When I Was a Boy”) are alluring.

This is that rare collection – one which has the capacity to widen the reach of poetry, appealing at once to dyed-in-the-wool poetry lovers as well as new audiences.

Lindsay Macgregor

Leave a Reply