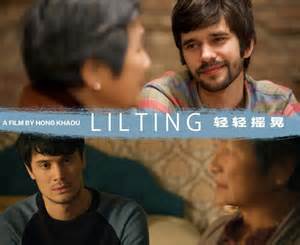

Lilting

Harold Pinter once remarked that silences were revelatory spaces “below the word spoken”. The last essay in Kei Miller’s Writing Down the Vision, “A space between the poems” turns on the word “space”; Miller’s incantatory repetition of the word, turning it around this way and that to pick up nuances of meaning, crafts a perfect hollow of “spaces that exist outside words”. Hong Khaou’s small, sensitive and unassuming gem of a film, Lilting, is likewise preoccupied with silences as the space between (or below) words spoken, and the untranslated spaces between languages. Lilting is about the truths we hide from each other, the lies that we tell one another, about translations and mis-translations, and above all how we can’t – or daren’t – make what’s inside outside as we speak with others.

Harold Pinter once remarked that silences were revelatory spaces “below the word spoken”. The last essay in Kei Miller’s Writing Down the Vision, “A space between the poems” turns on the word “space”; Miller’s incantatory repetition of the word, turning it around this way and that to pick up nuances of meaning, crafts a perfect hollow of “spaces that exist outside words”. Hong Khaou’s small, sensitive and unassuming gem of a film, Lilting, is likewise preoccupied with silences as the space between (or below) words spoken, and the untranslated spaces between languages. Lilting is about the truths we hide from each other, the lies that we tell one another, about translations and mis-translations, and above all how we can’t – or daren’t – make what’s inside outside as we speak with others.

Hong’s film is a story of twin bereavement; of Junn, an emigrant Cambodian (Cheng PeiPei) who speaks no English, living in a care home and grieving the recent accidental death of Kai, her only son (Andrew Leung); and of Richard, her son’s English lover (Ben Wishaw) who is still shell-shocked by his loss and who speaks no Chinese. Junn did not know that Kai was gay; Richard alternates between secrecy and revelation in his attempts to befriend Junn. Richard hires Vann (Naomi Christie) ostensibly to translate for Junn and Alan (Peter Bowles) who is courting Junn, but Vann also translates for Richard. The lean, wiry and bearded Wishaw brings a marvellous natural intensity to the part: flashbacks of conversations and tender caresses exchanged between the lovers in their bedroom (overexposed to create a luminous intimacy); nervous energy and exasperated shrugs in his desire to please both lover and mother; red-eyed outbursts of anger and frustration. Wishaw is a joy to watch and it’s obvious that the camera loves him. Cheng’s acting style is different; she alternates between a naturalistic facial passivity used to indicate a bewildered solipsism, accentuated all the more by the way the camera lingers over her close-ups, and the more traditional melodramatic Chinese acting delivery style, utilising heightened facial gestures and raised voice “harrumphs” to punctuate the more gentle comedy between Junn and Alan. Sections of Lilting feel as if they are shot as extended takes with a couple of cameras (or more) in a small enclosed space, but this accentuates the emotional resonances of the exchanges; viewers are encouraged to read between the words said or not said. In direct contrast to language, erected oftentimes as defensive, evasive barriers to who (or how) we are, bodily non-verbal signifiers of touch, facial tics, caresses, and shrugs in Lilting offer an expressive expansiveness that exceeds words.

The flashbacks in Lilting, some of which are repeated with only slight differences, indicate a trauma not easily resolved, a memory not easily let go of. These episodes function as traces and echoes of a presence that can’t, of course, now coalesce spatially: the whiff a body that once inhabited space, the dent in the bed that was once slept in, disembodied or soundless speech. Despite the dramatic potential of its plot line, Hung’s film is more of a mood piece. However, Lilting isn’t always so successful in exploring characters’ complex motivations. For example, Junn’s desire to be the most important figure in her son’s life is taken for granted rather than examined; defensive, hostile and vulnerable in equal measure, Kai remains an enigma; also, what exactly Richard wants from Junn is perhaps more complicated than meets the eye. That said, Junn’s lyrical epiphany about aging, memory and loss at the end of the film, diegetically motivated by Richard but actually addressed to no one and everyone, is perhaps the most moving sequence in the film.

Reservations aside, made under the Microwave funding and mentoring scheme from Film London, Lilting makes wonderful use of its shockingly small budget. It’s a shame that it was given only one public screening at the DCA.

Gail Low

Leave a Reply