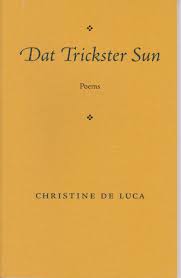

Dat Trickster Sun

Shetland native and Edinburgh Makar (appointed May 2014) Christine de Luca’s most recent collection poses, and obliquely answers, many questions so well. If a pamphlet might be termed a chapbook (originally cheapbook), then only in terms of the price, it might be that. However, from its elegant dull yellow jacket, its buff endpapers and Gerry Cambridge’ s restrained, beautiful typography in Jenson Pro and Carters Sans, Dat Trickster Sun makes a statement before a word is read. And that is entirely fitting.

Shetland native and Edinburgh Makar (appointed May 2014) Christine de Luca’s most recent collection poses, and obliquely answers, many questions so well. If a pamphlet might be termed a chapbook (originally cheapbook), then only in terms of the price, it might be that. However, from its elegant dull yellow jacket, its buff endpapers and Gerry Cambridge’ s restrained, beautiful typography in Jenson Pro and Carters Sans, Dat Trickster Sun makes a statement before a word is read. And that is entirely fitting.

Much is made of De Luca’s choice to write in English as well as in her own Shetlandic. There are those who prioritise the latter over the former in her work. Both tongues have been spliced through her considerable oeuvre for many years, and some of the themes here have long haunted her in previous collections (loss, landscapes, heritage across generations and continents). There is a real sense that the poems here push her Norse tongue further than was possible in, for example, the prose of And Then Forever (2011). In poetry she dares and trusts her reader more. And Then Forever ends with a very extensive glossary of Shetland words, which though helpful in places, seems somewhat patronising in others, particularly to the Scots reader. Yes, “Voar” required a translation, but did we really need bothy, burn, kirk and loch explained? In these poems, not only is De Luca’s Shetlandic far more sound dense, and joyous to read aloud, but her end-noted translations of the needful words in each of the non-English poems hit a better note. De Luca rides that MÓðir Dy (Mother Wave) bravely indeed.

In truth her English and Shetlandic sit well together in this master class in how to edit and sequence poems in a collection. There is even the occasional fun of false cognates – who does not enjoy an extra layer from “glanse” (“sparkle”)? Perhaps there is an argument to be made that the English poems have a different distance. I am unconvinced. De Luca has a right to write in both tongues – her years straddle Edinburgh as well as Waalls.

At da café, someen tried a puzzle med o wid,

a ticht knot. Takkin apairt was aesy; piece

bi piece, no bafft an brukkit tae a coose. Pittentagidder took mair is patience.

Why should she be pressed to choose? Burns didn’t. After all those years of Standard English tyranny suppressing languages from Shetlandic to Cornish, hidden in the present thrilling linguistic renaissance, is there now a slightly sinister backlash pressurising those who write in English and another tongue or dialect to use only the latter? If that pressure exists, De Luca is well-able and wise to resist.

More positively, it is indeed a time of great language renewal. In company with fellow Shetlander Robert Alan Jamieson, and more loosely with some of the finest contemporary poets working in both of their languages (Kathleen Jamie, Jim Carruth and more), there is no hint of the kailyard’s creeping nostalgia, although all write contemporary pastoral. The extreme topography and geology of Shetland sings throughout this collection, and de Luca is adept at considering family history and memoir equally (consider “Inteemation” and “The House Where I was Born”). With a historical and subject matter beyond Shetland’s and even Europe’s shores in both languages, she references Da Caald War, Costa Rica and DNA.

If we expect words for geological features, and for birds – tirricks (arctic terns) and laevriks ( larks), perhaps her poetry on cyberspace, and not in a simply jocular mood, comes as more of a surprise –

blogging, tweetin an aa

dis gödless, googlin, fae uncan waelin

trowe wir metadata, sturknin somewye.

Dat Trickster Sun moves subtly indeed through these pages, and its promise is fulfilled in the final, macaronic poem “Spelling it Out”, which both asks the questions about how we define language and dialect and gives the answers.

No, I won’t spell them out. You’d do much better to read Dat Trickster Sun.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply