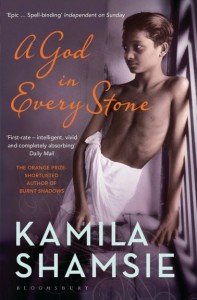

A God in Every Stone (Baileys Prize Shortlist)

Reading the runes of history as an intertext to the present, emphasising the circularity and tragedy of human lives or simply to give lie to the adage that the past is another country, has proved a rich novelistic seam. In the hands of a gifted writer such as Michael Ondaatje, archival texts, rendered with a luminous poetic sensibility translate different temporalities, imbuing the past with a contemporaneous urgency, but also delivering the present with the poignancy of a tale foretold. A God in Every Stone is reminiscent of The English Patient and Anil’s Ghost not only in its complex dance of betrayal, love, brutality and power fuelling Empire and its legacies, but also in Shamsie’s feeling for history and emotion realised in ancient stone, objets d’art and relics.

Reading the runes of history as an intertext to the present, emphasising the circularity and tragedy of human lives or simply to give lie to the adage that the past is another country, has proved a rich novelistic seam. In the hands of a gifted writer such as Michael Ondaatje, archival texts, rendered with a luminous poetic sensibility translate different temporalities, imbuing the past with a contemporaneous urgency, but also delivering the present with the poignancy of a tale foretold. A God in Every Stone is reminiscent of The English Patient and Anil’s Ghost not only in its complex dance of betrayal, love, brutality and power fuelling Empire and its legacies, but also in Shamsie’s feeling for history and emotion realised in ancient stone, objets d’art and relics.

A God in Every Stone begins with a romance between a young English woman, Vivian and her father’s friend before easing into the story of Qayyum Gul, a Pashtun who served with the British Indian Army at Ypres, and his young brother, Najeeb, who becomes Vivian’s student years later. Together with two women, Zarina and her sister-in-law, Diwa, the Gul brothers and Vivian are caught up in the massacre of Peshwar non-violent protestors in 1930 which forms the novel’s climax, an event hushed up by the then British colonial administration. These entangled lives and fates are book-ended by references to Scylax and King Darius, the former, a trusted Carian explorer who later sided with country’s rebellion against the latter, such layering also serving as a reminder of the geographical fluidity of the Ancient world. Love and betrayal, played out both in major and minor keys become recurring motifs: Vivian’s unwitting betrayal of her lover to gain attention; Qayyum’s love of the British and their betrayal of his trust; Qayyum’s love, and also disavowal, of Kalam who saved his life at Ypres; the knot of hurt, love and loss the brothers share; and more besides. In the run- up to that fateful day of the massacre, Zarina and Diwa’s stories are woven into the novel’s main threads. That these women take centre stage during the massacre’s rendition is strategic to the book’s sexual politics. In doing so Shamsie gives these women’s lives, consigned by history as all but invisible, pride of place.

Too many fault-lines between stories and themes make a seamless closure difficult; the romance plot which provides the text’s MacGuffin is also a little irritating. Yet, in her strategic navigation of shifting perspectives, we also come to understand the naivety – but also – the necessity of love, the poignancy of betrayal, the urgency of anger, heart-rending loss, and the power of art. Shamsie’s language is less poetic than Ondaatje’s but the censure implicit in such a judgement is also unfair. With more emphasis on story and character than its rendering, Shamsie’s writing is quieter and less showy, bending language to the fictional lives of her protagonists with metaphors that create mood, building emotional bridges between characters and readers. After Oayyaum’s return, we are told that Najeeb “sat at the very edge of the bed-frame, watching his brother eat… the only one in the family who met Qayyum’s silence with silence instead of an increasing pitch.” Given his troubled past, we feel the full emotional force of Qayyum’s wide-eyed surprise at the power of art:

The folds of the prophet’s skin suggested the former sleekness of the prince he had been; the sunken eyes bore knowledge of all the world’s sorrow…. Stone made flesh; no, stone made bone and skin. If a man rested his hand on that cage he might hear a heart beating within; but gently, gently… He shivered and stepped back; now he understood idolatry… and the Buddha continued to gaze beyond him, all of Vipers there in his eyes, every dead soldier, and Kalam Khan bleeding to death, cold and alone.

As an aesthetic endeavour, words becoming flesh, there is much to wonder at in A God in Every Stone and little to forgive.

Gail Low

Leave a Reply