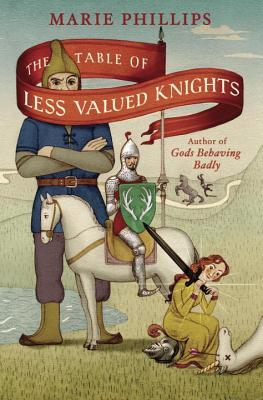

The Table of Less Valued Knights

“On second thought, let’s not go to Camelot. It is a silly place anyway.”

“On second thought, let’s not go to Camelot. It is a silly place anyway.”

Despite having fallen in and out of favour with its audience several times over, Arthurian myth is a cornerstone of the British literary canon; it’s been the subject matter for poems, plays, novels, paintings, operas, and films, and is thoroughly embedded in popular culture. However, as with any long established iconography, this leaves Arthuriana open to pastiche and, in the vein of Monty Python and the late, great Terry Pratchett, Marie Phillips turns her satirical wit from the Greek myth of Gods Behaving Badly to the quest riddled Britain of King Arthur’s court.

Drawing her cast of characters from a selection of familiar archetypes, Phillips weaves a ridiculous romp from the best known strands of the knightly quest narrative. Featuring a disgraced knight, a runaway queen, a damsel in distress, and a villainous prince, Less Valued Knights sets out on a quest to debunk the preconceptions of its subject matter through a combination of subversion and incongruity; King Arthur is a bore, the knights are pompous, the damsels are base, and sorcery is not so much mystical as it is bureaucratic. Like Pratchett, the Pythons, and indeed Mark Twain before her, Phillips presents us with a humorous take on “history” as viewed through a contemporary lens.

Though Phillips’ writing style may strike readers as rather simplistic, her prose reads with fluid brevity, doing away with knightly rhetoric and instead presenting its Camelot with a great deal of frankness, upon which the author relies for comedic effect. Her characters converse in a contemporary British vernacular, the laughs springing from the collision of contemporary pragmatism and logic with the stock elements of the quest narrative. Dwarfish customs officials quibble with questing knights over the protocol of allowing an elephant (“deformed horse”) over the border between kingdoms, the “Locum of the Lake” is a stand in for Nimue, who “ran off with Merlin”, and was promoted to the position after taking “a module in Divination”, and the villainous would-be-king is a misogynistic “lad”, repeatedly disappointed with the reception of his “what king? Fuc-king” gag.

Phillips’ approach to her material is nothing new, but her execution exhibits a knowledge and appreciation of Arthuriana that buoys up the narrative even when some of the jokes fall a little flat. Indeed, though The Telegraph writes that the author “achieves a banality of her own with her often pedestrian prose” and decries that “the male characters tend towards the oafish […] the female ones towards the pathetically supine”, it is worth remembering that the author’s aim is to lampoon, and so such exaggeration of the male and female qualities of her characters befits their purpose. So, while the style of Less Valued Knights might seem brash and, at times, bawdy, it is a fitting manner in which to undermine the chivalry and romance of the Arthurian quest. However, though mockery is the aim of the game, Phillips’ treatment of the gender fluidity and sexuality of certain of her characters gives not only a liberal championing of contemporary issues, but an incorporation of the mediaeval motif of the cross-dressing saint, blending the past with the present for comedic effect.

This is not to say that the novel is without its flaws; though the ending conveniently resolves both quests, crossing every “t” and dotting every “i”, it does so in the matter of a few pages and borders on the twee. The humour, too, occasionally feels a little overstretched, though these instances are rare enough to avoid becoming a real problem. Indeed, these complaints are relatively minor, and The Table of Less Valued Knights remains an easy, pleasurable, and amusing mockery of and tribute to the knights of Camelot.

Ewan Wilson

Leave a Reply