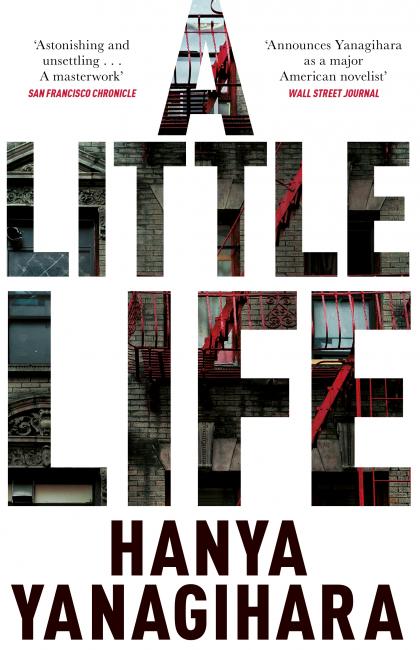

A Little Life (shortlisted for the 2016 Baileys Prize)

A Little Life seems to be the favourite to win the 2015 Booker Prize. But before allowing it to be celebrated as the great gay American novel everyone’s been waiting for (as some have), the following observations may be relevant..

A Little Life seems to be the favourite to win the 2015 Booker Prize. But before allowing it to be celebrated as the great gay American novel everyone’s been waiting for (as some have), the following observations may be relevant..

Jude, abandoned as a newborn, grows up in care and is serially sexually abused by scores of men from the monks who find him and pimp him out to others to the psychiatrist who keeps him as a dungeoned sex slave. He eventually becomes romantically attached to Willem his friend of many years but is unable, understandbly, to enjoy what might be considered a normal relationship. There have always been unfortunate people who have in real life suffered excessive mistreatment like this. But real world liabilities are not the same thing as the responsibilities of fiction, of which more in a moment.

It is never clear that Jude has the agency to express a truly personal sexuality. His sexual activity seems always to have been chosen for him, brutally at that. His more settled modus vivendi with Willem is by mutual consent asexual, with Willem seeking relief elsewhere. Any expression of sexual desire, on this conspectus, amounts to coercive social expectation, and is never genuinely voluntary, free of the tyranny of enforced behaviour. Love does grow between the two men; but insofar as sex matters in their relationship, it matters by its absence. Because Jude is so broken, so self-harming (he cuts himself with razors throughout), so unhealed and unhealable, he cannot embody the fullness of any kind of sexual identity or experience.

Some have suggested that this novel’s hyperbolic, melodramatic mode is a milestone in the representation of gay male sensibility, which is allegedly prone to grand guignol. But there is no unitary gay male sensibility; and supposing there was, camp is not necessarily its default position.

The novel’s title recalls lines from Pope’s Windsor-Forest, in which hunting beasts “learn of men each other to undo”; and where thanks to predatory shooters, “Oft, as the mounting larks their notes prepare, / They fall, and leave their little lives in air” (ll. 124, 133-34). A Little Life broods similarly on vulnerability. Everything it says about this seems well worth saying; and as a study of pathos and waste it would be hard to beat. The human vulnerability it explores is as terminal as for Pope’s slaughtered skylarks. Friendship, no matter how permanent, committed or self-giving, is simply powerless to offset what was done to Jude in his youth. Offered repeatedly, and confirmed again and again over many years in importantly different ways, human attachment cannot save Jude from the damage of unkindness, or from suicide, which it appears would’ve happened anyway. His author has done too thorough a job of blasting Jude out of the sky, for this to be any more than a fiction gesturing towards a notionally gay tragedy.

What then stands in the way of attributing major significance to this novel? There are two reasons it shouldn’t win the Booker. First, its “worthiness”. Worthiness may justify a novel’s addressing this or that hitherto overlooked theme, social problem or human type. But it does not necessitate the novel as literary form, whose primary duty (as Henry James insisted) is to itself. Worthiness is a kind of didacticism; and while novels may teach, incidental to their formal structuring, teaching feels like the main point of A Little Life. Journalism or memoir might have done that better.

Secondly, this novel is only the sum of its parts; and even then, it grows somewhat tired towards the end. Any work of art in any medium has to be a gestalt, energetically transforming its elements into more than themselves. That’s not happened here. One is pleased to see someone like Jude duly presented fictionally. But this is a novel of record. The pleasure is documentary. Like Jude himself, and Pope’s terminated larks, it doesn’t sing.

Jim Stewart

Jim I read A little Life over the festive season and I enjoyed it as a novel. I found the history of Jude’s life horrific, but extremely hyperbolic. How `unlucky` to find a main character entering into one abusive situation after another. That said I found myself becoming less and less sympathetic to Jude throughout the book. Not because of his dreadful history but because of the constant need of the author to remind us of his contemporary plight. The refusal to accept, at face value ,the love offered by his circle of friends, Harold, JB, Malcolm etc. is a conundrum on its own. Considering Jude’s past, I found his inability to forgive JB for his post crystal meth behaviour a little surprising. I cannot appreciate the great gay novel accolade, simply because I do not appreciate what that is. Perhaps the all male relationships, explicit in this case, implicit in say perhaps Wilde’s Picture of…is the key to explaining what a great gay novel actually is. A Little Life – A Series of Unfortunate Events for grown-ups, well for Jude anyway?