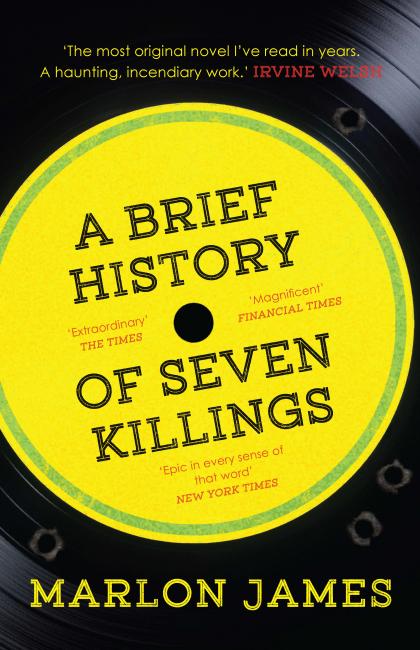

A Brief History of Seven Killings (Winner of the 2015 Man Booker Prize)

Last autumn, I asked Kei Miller for the names of contemporary Jamaican writers he thought I ought to read. The first name on his lips was Marlon James. I bought The Book of Night Women and A Brief History of Seven Killings, but as is the way of many good intentions, both titles overwintered unread on my crowded bookshelves. Now with the latter shortlisted for the Booker Prize, and tasked with the urgency of reviewing, time just had to be set aside.

Last autumn, I asked Kei Miller for the names of contemporary Jamaican writers he thought I ought to read. The first name on his lips was Marlon James. I bought The Book of Night Women and A Brief History of Seven Killings, but as is the way of many good intentions, both titles overwintered unread on my crowded bookshelves. Now with the latter shortlisted for the Booker Prize, and tasked with the urgency of reviewing, time just had to be set aside.

At 688 pages, A Brief History is anything but brief: an ambitious, sprawling and complex door-stopper of a novel that really needs to be read in one continuous sitting, or as near to it as possible. With a cast of over seventy characters in the timeline of the attempted assassination of Bob Marley in 1976 and its contexts — the gang violence, ghetto and political tribalism of seventies Jamaica, the realpolitik machinations of CIA agents to engineer Cold War advantage — this was always going to be a text that pushed the boundaries of the (historical) novel form as well-wrought urn. Influenced by the stream of consciousness and the multiple narrators of William Faulkner’s As I lay dying, and including more than a nod to William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch with its drug-fuelled cast, phantasmagoric hallucinations and tribal nomenclature, James’s novel requires you to hang onto its various threads and voices as the book moves inexorably towards the attempted killing, its symbolic portent and then beyond.

To stay the course is to be plunged into a swirling, bewildering cauldron of voices and experiences, all driven by elemental needs: hunger, love, power, survival. These competing, sometimes minimally punctuated monologues (both Jamaican and American), are cut and stitched together without an extra-diegetic narrator to build distance. Rare, occasional surface time comes in the form of wry and ironic commentaries by the duppy (ghost) of a murdered politician, Sir Arthur Jennings, but these accentuate pathos rather than offer relief. Some voices matter more (Nina Burgess — and her identity switches — Papa Lo, Josey Wales, Bam Bam); others may add historical and political ballast but you never really care for them in the same way. Many are given a depth of character that complicates your relationship with them, despite the crimes they routinely commit. But not all are equal nor handled with the same surety of touch; Sir Arthur notwithstanding, the Jamaican characters born on the wrong side of town are more finely wrought and handled much more fluently. These are the ones you care deeply for.

A Brief History’s mostly testosterone-fuelled primal urges bring to the fore humanity’s inhumanity to (wo)man: drug-fuelled gang violence, causal cruelty and calculated punishments, the exploitation by those who can of those who can’t. Yet James narrates with a wonderful vernacular lyricism, binding darkness with beauty. We follow Bam Bam initially as a young child who witnesses the shooting of his parents. The account captures the rape of his father; the shock of the killing; the urgency of fleeing; the pathos of the life that could have been:

As I wait my [dead] father on the floor by the door and he get up and come over to me and say English is the best subject in school because even if you get a job as a plumber nobody going to give you any work if you chat bad, and chatting good is everything even before learning a trade. And that a man must learn a trade.

The whole gamut of emotions is bound together through a kind of metonymic invocation: the Clarks shoes on his dead father’s feet. Later, Bam Bam learns to kill and we are not allowed to look away from the consequences of violence or to glamorise. “The piss and shit and blood”, as well as the emotional numbness, are all there. The living, messy, lyrical novel that is A Brief History of Seven Killings is demanding, but what an astonishing read it is.

Gail Low

Leave a Reply