Before I knocked

“Before I Knocked” – the title is from a Dylan Thomas poem – focuses on three images from the past: a postcard sent from California to Belfast in 1931; a photograph of two British soldiers in Jerusalem during World War II; and a family snapshot taken on an Irish beach in 1954. The essay unravels/imagines the connections that link these images. What follows is the current draft of the opening section.

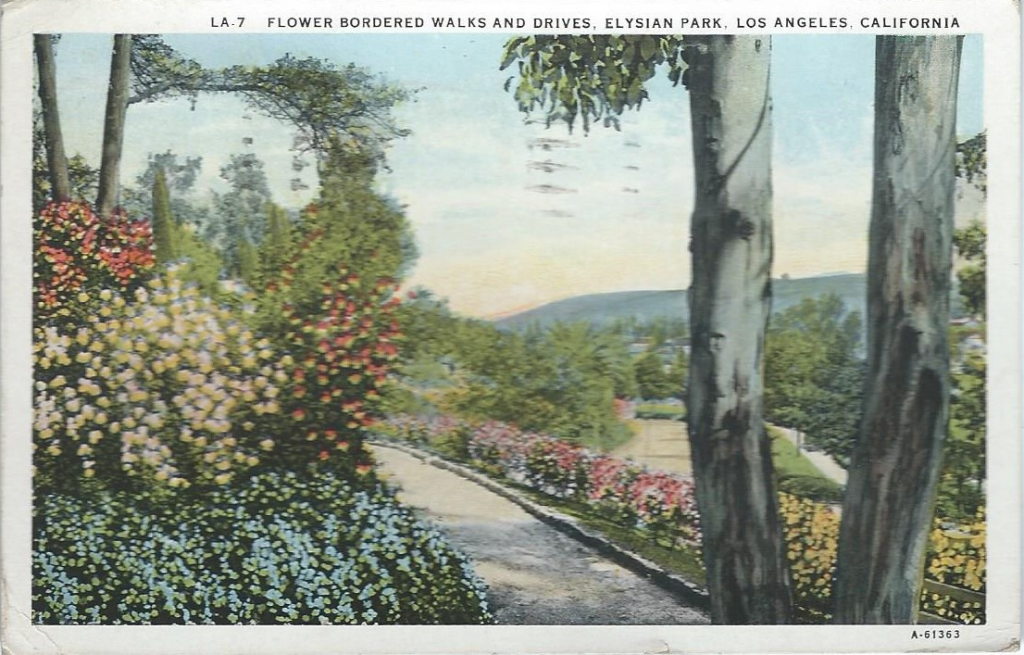

“Flower Bordered Walks And Drives, Elysian Park, Los Angeles, California” is the title that’s printed on the narrow white frame that borders this picture postcard. To a contemporary eye, what’s immediately apparent is a sense of datedness. The poor quality of colour and resolution acts like a fingerprint of out-of-date technology. Pictures like this haven’t been produced for years. This is an old postcard; it verges on the antique. I’m not sure when the photograph was taken. The card looks similar in style to one that’s marked “Mailed in 1910” in a selection of Elysian Park postcards displayed on www.image-archaeology.com, a website whose name alone points to a rich stratum of inquiry for anyone interested in recovering the fabric of the recent past.

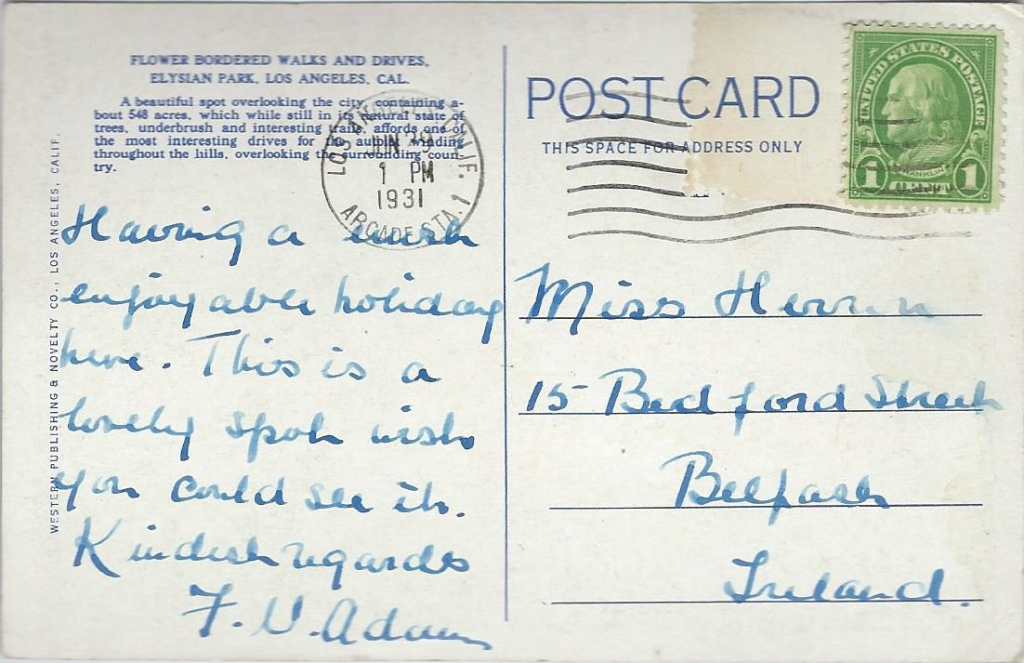

Whatever year the photograph was taken, I know this postcard was mailed in 1931. Inside the black circle of the postmark is printed: “Calif. Arcade Sta. 1 Jun 29 1PM 1931”. It’s addressed to “Miss Herron, 15 Bedford Street, Belfast, Ireland”. The message on the card, like the address, is written with a thick-nibbed fountain pen. The blue-black ink has begun to fade. It says: “Having a much enjoyable holiday here. This is a lovely spot wish you could see it. Kindest Regards, F.W. Adams.” This eighty-four-year-old message only carries a single one-cent stamp, but a yellowed space beside it suggests that, originally, a second stamp accompanied it.

The postcard was given to me by a friend in Ireland who knows my liking for such shards of history. She found it among papers she was going through after her father’s death. “Miss Herron” was a distant, only hazily remembered relative; who “F.W. Adams” was, nobody now remembers. I’m fascinated by this little piece of card sent across the Atlantic years before I was born. This isn’t because of what’s written on it. Its variation on the hackneyed theme of “Having a lovely time, wish you were here” isn’t interesting at all. The postcard appeals to me for reasons that have little to do with what it says.

Part of the appeal lies in the way it acts as a tiny uncurtained window giving a tantalizing glimpse of other lives. It’s like a spyhole that offers a peek into someone else’s room. Looking at it reminds me of nighttime train journeys when the carriage passes close by lighted houses and, for a moment, cameo scenes of their occupants are vividly displayed. Despite their ordinariness, these scenes are sometimes so striking in their brief moment of illumination that they can seem like icons depicting how other people live. Of course the postcard sparks a raft of questions. Who was F.W. Adams? What was the relationship between him, or her, and Miss Herron? What did Miss Herron think when the card arrived and she recognized the handwriting? Did it spark a smile of recognition? Make her frown? Was she pleased that F.W. Adams was having a “much enjoyable holiday” or disapproving of such an expensive foreign jaunt? And what stands behind that oddly formal “F.W.” of the signature? Was it Frank Wallace? Frances Wendy? Frederika Wilma? Was withholding a name just the convention of 1931 postcard writing, or might opting for initials reveal where F. W. Adams stood on a contour map of class, gender, nationality, or age? This little splinter of communication gets under the skin of the imagination and prompts a whole ream of possibilities. The clues it gives are sparse, but they spark countless scenarios of human interaction.

Another reason I find old postcards like this one appealing is because they offer such precise coordinates of when and where. In doing so, they almost seem like pieces of petrified time. What was once a now is caught in the teeth of this sprung card-trap, the moment preserved in the amber of its ink. This postcard is a tangible fragment of June 29 1931 at 1.00 pm. Holding it brings powerfully to mind the lives that were being lived at that vanished moment alongside those of Miss Herron and F.W. Adams. The card’s smallness, the fact that it represents so tiny a part of the great buzz of humanity, seems to summon an awareness of the belittling cornucopia of lives happening around the two it names. And I realize, as I scrutinize it for further clues, that in the maelstrom of lives and events of which it’s such a minute remnant, the threads were being woven that would eventually lead to me.

I’m particularly drawn to this postcard because I can connect it with my father’s life. June 29 1931 – my father is twenty-six, working as a civil servant. He’s living in Belfast, not far from Miss Herron’s Bedford Street address. It’s almost certain he’ll have walked past her door on more than one occasion since her house is in the same street as a theatre he frequented as a young man. Did their paths ever cross? Might they have exchanged a glance? How strange to think of a look passing between them, neither knowing anything about the other, and how each of their lives continued from that moment in all the intricate particularity that created the histories they embodied. In eight years from the now preserved in this postcard, Dad will leave his job to fight in World War II. He won’t get married for another eighteen years. In 1931 he’s not even met my mother. She’s only fourteen when F.W. Adams was visiting Elysian Park. What, I wonder, was she doing, the girl who would become my mother, at the precise moment that F.W. Adams licked the stamps and put the postcard into a mailbox in California? I know she’s living on a farm in the County Antrim countryside not many miles from Belfast. It’s likely that she too will have walked down Bedford Street – her mother had friends who lived near there. In fact she might easily have passed by Miss Herron’s door, perhaps even glimpsed the tall, dark-haired young man walking by who was to become her husband. When I look back at – or imagine – these encounters now, decades later, I’m filled with a sense of the precariousness of individual being. How easy it would be for any of us never to have existed.

I’m pleased to have the convenience of electronic communication. But somehow texts and emails don’t have the same appeal as something that was there, in that place, at that time; something that was held in the hands of those named on it. The postcard has the authenticity of presence. It acts as a tangible particle of vanished time, a token of lives now over. It summons them back to mind in a way an email couldn’t. I realize that the postcard’s obsolete, just junk – it’s long served whatever purpose F.W. Adams may have had in sending it. The writer of the card and its recipient would doubtless have been astonished to find people eavesdropping on their business all these years later. Listen! You can almost hear Miss Herron tut-tutting at the ill-bred nature of such spying. Yet I’m reluctant to heed her and throw the postcard out. It’s poised to cross the uncertain border that runs between the mundane and the historical. I suppose any artifact becomes interesting if it’s kept for long enough. I don’t want to disturb the slow metamorphosis of this little splinter as it works its way out of the ordinary and into the realm of the revelatory. Soon it might warrant a place in a museum. In any case, the Elysian Park postcard has recently acquired additional value because of how it relates to two other images. Put together, they form a kind of triptych whose interconnections fascinate me.

© Chris Arthur

Leave a Reply