The World Before Snow (Shortlisted for the 2015 T S Eliot Poetry Prize)

Tim Liardet

(Carcanet, 2015); pbk. £9.99

Tim Liardet’s The World Before Snow, his second collection to be nominated for the T. S. Eliot Prize, is described by Carcanet as “a book of passionate extremes.” Inspired by the poet’s chance meeting (and subsequent love affair with) an American poet after the two were trapped in a Boston museum during a snow-storm, the collection showcases the transformation and self-exploration Liardet underwent following this encounter. This is a collection of contradictions: of loose and tight images, long and short stanzas.

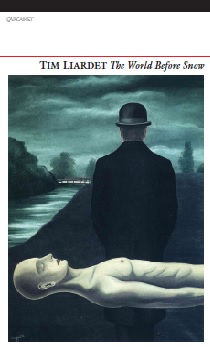

Even the cover prepares the reader for these binaries. René Magritte’s The Musings of a Solitary Walker (1926) is painted in incandescent whites and matte blacks, illustrating the collection’s achromatic and opposing dualities. Completed fully eighty-seven years before Liardet’s book, the image perfectly encapsulates the notion of the self being composed of multiple personas: the cover’s “solitary walker” depicts one man naked, horizontal and white, while the other clothed, dark and upright, faces away. Throughout, Liardet suggests these opposing versions of the “self”, which he explores in his numerous “Self-Portrait” poems, are themselves constructed through conflicting notions of love, which in turn he describes as “the havoc at which you cannot balk.”

Where some poems here, such as “Verte” are excluded from the “Self-Portrait” series, their forms are fairly standard, laid out in long stanzas, rendering the images easy to follow across the lines. The “Self-Portrait” titles, however, are presented in two-line stanzas, often enjambing sentences over two or three stanzas. Frequently this has the effect of losing images in the pages’ whitespace. What remains is akin to an overexposed photograph, suffering blurred edges and leaving only an indistinct impression. Such stylistic experimentation with form is nonetheless extraordinary when we consider the kernel of all these poems: two poets trapped in a blizzard, startlingly similar to the two lines of poetry, lost in their pairings in a sea of white.

The idea of pairing and binaries is further emphasised by the “Self-Portrait” titles, which often include opposing or incongruous couplings. Consider the honest person visiting a confessional in “Self-Portrait as Truth-Houdini at the Confessional Grille.” Additionally, “Self-Portrait with Flowershop Idyll and Nihilistic Love”, suggests both extreme happiness and meaninglessness in regards to that state. This contradiction continues throughout the poem as the narrator’s experience of love is first described as unpleasant, personified to cause pain and discomfort:

Our love licks salt, cracks fleas. Plucks hairs.

[…]

It will, being hungry, have us as victims.

However, these descriptions are interwoven with others, pronouncing love as something subtle and affectionate:

Attentive to each other, inclined to touch, in our long coats,

we have hands in each other’s pockets, hands in each other’s hands,talk in each other’s mouths.

Here, the poem not only showcases Liardet’s duality in images and language, but it also demonstrates his idea of the constructed “self” and his understanding of how we form our identities. A self-portrait, like an autobiography, is an investigation of the subject by the subject, and therefore can only feature the artist, however Liardet’s “self” is anything but unified.

Another recurrence is the non-“Self-Portrait” title, “Ommerike”, which is situated as the introductory poem to each of the four sections. Named after what North Atlantic sailors first referred to America as, the opening poem speaks of first impressions, as well as something new and mysterious. The initial word “We” and subsequent use of pronouns: “you and I meet and fall, meet and fall…”, illustrates the introduction between Liardet and the American poet, the first person confirming the autobiographical and self-exploratory nature of the collection and the “havoc” of love: “meeting and fall[ing]”.

The World Before Snow is a flurry of images, often blurred in form against the white outs of the page and is full of contradictions and extreme passions. Is there a reader alive who cannot relate to that cacophony of feeling induced by his well-named “havoc” of love?

Kate McAuliffe

Leave a Reply