An Interview with Jim Hinks of “MacGuffin”

On the 11th November 2015, I was fortunate enough to interview Jim Hinks, who is Project Lead at Comma Press for their latest piece of software, MacGuffin – available as an App for iOS or Android, as well as a website. As the press release says:

On the 11th November 2015, I was fortunate enough to interview Jim Hinks, who is Project Lead at Comma Press for their latest piece of software, MacGuffin – available as an App for iOS or Android, as well as a website. As the press release says:

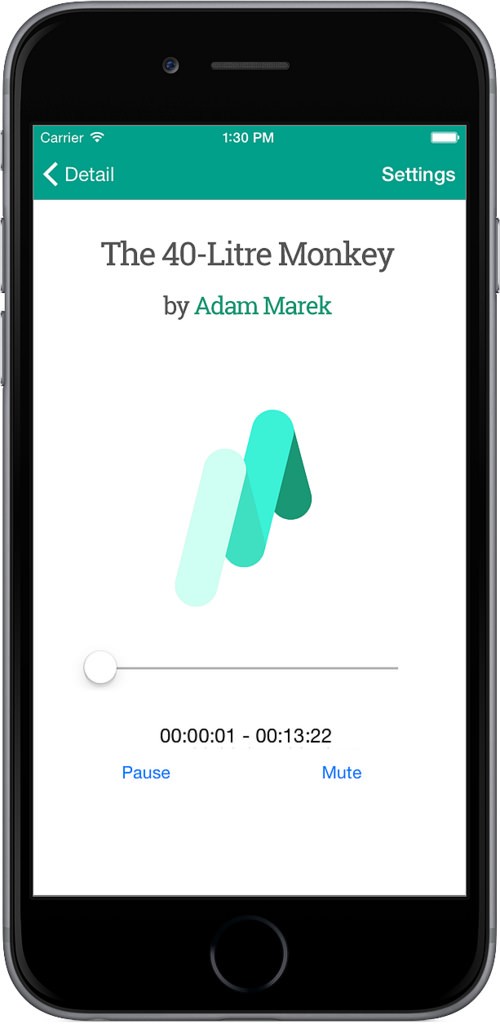

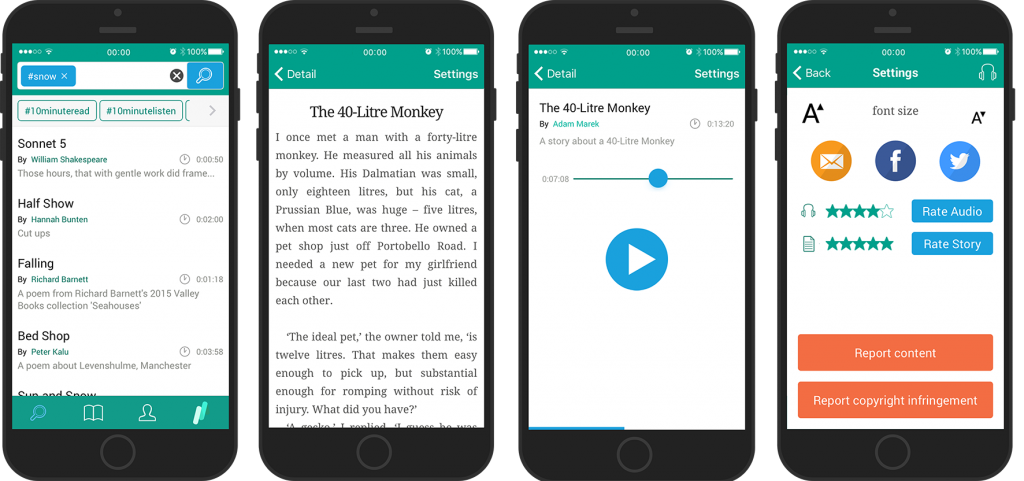

“The MacGuffin App has a simple, yet revolutionary, innovation: all content is in text and audio form, so users can read the text, stream the audio on the go, or toggle between the two. It hosts free fiction and poetry from some of the UK’s leading independent publishers and spoken-word nights. It’s also a self-publishing platform. Anyone can publish their own content to MacGuffin, via the website, so long as they also upload a reading. MacGuffin creator Jim Hinks says, “Amateur podcasters have shown in recent years that technological barriers to entry have fallen away. You used to need a recording studio. Now anyone with a smartphone, a quiet room and some talent can create brilliant audio content.”

Based on my own experience using the App on Android and iOS, and having read the press release in detail, I had lots of questions!

Lorna Hanlon: Hello Jim, thanks for giving me some of your time to talk about MacGuffin. Can you firstly tell me how the name came about? Most people will know about the link with the films of Alfred Hitchcock, which always contain a MacGuffin – a plot device which seems to mean everything and leads in other directions, but is this name a red herring?

Jim Hinks: The name came very late in the process – one of my favourite names was originally “No Comment” as my feelings on the comments posted on self-publishing platforms have been that they are generally either over-effusive or have a tendency to create arguments & negativity. The team who were involved were all big fans of Hitchcock, and we threw around loads of ideas, but we also had to be able to trademark it. This might sound quite aggressive and corporate, but it is in fact a defensive move to protect the software from other corporations. We found that MacGuffin wasn’t a registered trademark.

LC: So MacGuffin it was! How was the idea itself born and how did it develop?

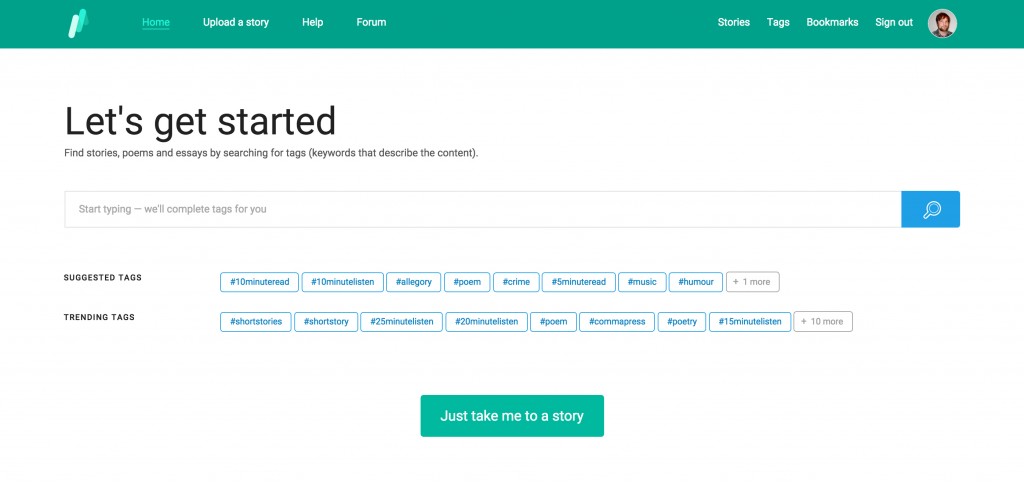

JH: We originally built a short story app Called LitNav – commuters liked it, as it had a category section that allowed users to select stories according to listening time. MacGuffin’s really a development of that idea, but it puts end-users in charge of the categorisation: anyone can add tags to anyone else’s work. As more content is added and tagged, it builds into an archive of community-curated content. So for example you can search for “poem” and “snow” to find poems about snow. For me the breakthrough moment was looking at other apps and websites, and at how they used keywords. In 2013 we heard about the Digital Research and Development Fund for The Arts; we were lucky to find a funding strand which coincidentally fitted exactly what we wanted to do. So we started in 2014 with a design jam – a discussion with readers, writers and creative writing teachers, all contributing ideas about what they wanted in the Apps. Then we did a lot of testing with people and the website was launched at the end of June 2015, with the Apps soft launched at the end of August. Apps with full-functionality were released a few weeks later.

LH: Jim, in the press release you say “anyone with a smartphone, a quiet room and some talent can create brilliant audio content”. How long do you think that has genuinely been the case, and do you feel that you are filling a gap in the market which has not been filled until now? Or is a market gap something which is perhaps not relevant, as the App and website are free to use, and not-for-profit?

JH: There are other places for uploading audio – Soundcloud and AudioBoom for example – but nowhere does self-publishing in text and audio form the way we do, although I have seen a few curated platforms with a small selection of commissioned stories in text and audio form. From an end-user point of view, it’s unusual to have the option to toggle between audio and text, as you do on MacGuffin. This can of course present a barrier to writers. Of the now c. 900 stories that have been uploaded, nearly 30% are in draft form and not published yet, and these tend to have the text, but not the audio. Motivated writers will try it, recording at home on a phone, and in fact a lot of my favourite recordings have background noise, like children playing or dogs barking, and that’s fine and often adds to the charm, so long as it isn’t too distracting. The team have been trying to provide support as to how to record audio on the help pages and there will be a video available for guidance.

LH: That sounds like it will really help those who struggle with uploading audio. I notice you offer live recordings by spoken word performers – do these tend to be incidental recordings which are uploaded at a later stage, or are they specially recorded with MacGuffin in mind

JH: It’s a bit of both, as it was originally a short story platform, then poets became interested and got in touch. When we launched the website we wanted to go out and about with recording equipment to record at live events, and now people have started recording the content themselves. MacGuffin is well-suited to that because you can put in a search for a particular spoken word night and experience the audio as if you were there.

LH: How is MacGuffin achieving the aims of the Digital Research and Development Fund for The Arts, from which it was awarded funding?

JH: The research question was “can the tagging functions of platforms like Twitter be applied to literature, to help us learn about changing reader behaviour and taste?” So part of what we’re doing focuses on the analytics – how people are consuming content. Of course, some social media platforms use analytics in an underhand way – they use your data to sell to advertisers; they collect the analytics to sell to anyone. With MacGuffin, nothing is hidden; the analytics are available publicly, and anyone can look and see how many people have read each piece of work, and you can also see where readers are leaving the text. Naturally, the analytics don’t tell the whole story. The location data is deliberately ‘fuzified’ for privacy reasons, and doesn’t show demographic information, like the age or sex of the readers, but that’s the way we want to keep it. In terms of selling books, MacGuffin is free to use for readers and writers, non-profit and non revenue generating, so it isn’t the place for publishing a whole novel, but it’s great for finding new authors. You can follow links back to the publisher’s website, where you can buy the book, etc.

LH: That sounds like a very open and informative approach. The Digital Research and Development fund for the Arts allowed you to have the platform and the apps as they are, without advertisements. How long do you see that continuing for?

JH: Now that we are wrapping up the build, of course we have to look at sustainability. We have the funds to take us at least through the next year. Thereafter, we might need to look at ways of monetizing it which are in line with our ethos, namely more investment without introducing advertising. We might look at crowd-funded donations as the user base goes up and server costs increase, although there’s very little moderation – the way the website’s built – with automatically updated categories of ‘trending stories’ and ‘highest rated’ and so on. MacGuffin kind of looks after itself.

LH: And on the subject of moderation of content, if anyone can publish their own content, what editorial control is there over that?

JH: The content restrictions are quite simple – don’t infringe copyright, don’t libel or defame, don’t discriminate, and don’t give instruction to do violence or harm. When you publish on MacGuffin you retain your own copyright, and contributions go straight up onto the Website and Apps with no edit. There is an established community of writers on McGuffin from all over the world and beyond  Comma Press’s network who are so good that they are setting the standard. In a recent survey users were asked if they went on MacGuffin for specific authors; 62% of people said they were just browsing, and 71% said that they thought the content was good or very good.

Comma Press’s network who are so good that they are setting the standard. In a recent survey users were asked if they went on MacGuffin for specific authors; 62% of people said they were just browsing, and 71% said that they thought the content was good or very good.

LH: I can vouch for that, having read an excellent variety of pieces on MacGuffin! Of course there are many classic works on the website – where have they come from?

JH: Many of those are public domain recordings which were already out there – they came from Librivox, which has a huge archive and public domain licence. Some readers have worked directly with authors and sought permission from the author to record their works. There are some excellent sound design poems, which are home projects – users have recorded classic poems and mixed 3D sound design into them.

LH: That sounds fascinating – I must have a listen! Given that there is always discussion surrounding the future of books, that the downloaded book market seems to have shrunk again somewhat and that there is a resurgence of people buying hard copy, what is your opinion on how the market for literature is at the moment, and what do you think the future holds for publishing and literature and the way we will be reading or absorbing books of all genres in the coming decades?

JH: Ebook sales have indeed gone down; that’s partly a fashion thing, of course. It’s more hipster these days to have a book and hold it, to be analog! It also has to do with digital devices; when they started to add all the other stuff onto E-Readers that distracts people from reading, that also lead to a downturn in Ebook sales. Literature has always had a problem with the Internet. Reading is essentially an analog activity, but these days marketing and publicity are digital activities. It’s the way we share things and what social media does so well. Social media and deep reading of literature do not go well together, but audio content (such as the content on MacGuffin), helps you get away from the distractions – when you are in the bath listening to a story, there’s not the constant temptation to look on Facebook at the same time, you can just listen. In fact audio may remain a stable format. We don’t know what kind of text screens we will have in the future, so it’s hard to know if people will have devices which are good for reading text. But there is a futureproof quality to audio. We’re always likely to want to listen to stuff while doing other stuff. Publishers have invested a lot in audio content recently, and regardless of new formats, audio might turn out to be a safe investment. It’s very hard to predict what the future will hold but audio will likely hold its place.

LH: That’s a very interesting analysis of some of the ways we might be reading or rather listening in the coming years! Thank you for your time Jim, and I wish you and Comma Press every success with MacGuffin. I’ve certainly enjoyed what I’ve read so far, and would recommend it to anyone looking for a quality fix of literature, new or old, whether you’ve got an hour in the bath or five minutes on the train!

Leave a Reply