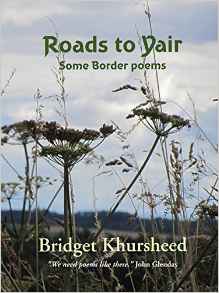

Roads to Yair: Some Border Poems

Recipient of the 2014 Scottish Book Trust New Writer Poetry Award, Bridget Khursheed was already known by many on the poetry circuit before the publication of Roads to Yair. Some may argue that her approach to poetry is hardly traditional in that very tradition-aware part of the country, but there is no doubt that her use of imagery has the capacity to fell her doubters. Khursheed has a wealth of knowledge of Scottish history, most notably (as in this collection) that of the Borders. She uses this to her advantage, weaving together poems which combine heritage with the present, nature with wisdom, and loss with hope. Her stated aim is to do with poetry what many before have done with song, “capture a contemporary truth that lies somewhere between the map, its roads and rivers and the landscape.”

Recipient of the 2014 Scottish Book Trust New Writer Poetry Award, Bridget Khursheed was already known by many on the poetry circuit before the publication of Roads to Yair. Some may argue that her approach to poetry is hardly traditional in that very tradition-aware part of the country, but there is no doubt that her use of imagery has the capacity to fell her doubters. Khursheed has a wealth of knowledge of Scottish history, most notably (as in this collection) that of the Borders. She uses this to her advantage, weaving together poems which combine heritage with the present, nature with wisdom, and loss with hope. Her stated aim is to do with poetry what many before have done with song, “capture a contemporary truth that lies somewhere between the map, its roads and rivers and the landscape.”

The collection takes the reader on a journey through the Borders in both time and location. “The Clovenfords vineries” starts the collection off in the village of the same name where, notably, the watchful statue of Sir Walter Scott stands. There are several significant references to Scott throughout the collection which may signify Kursheed’s love of the historical writer’s work, and the land that figures in both their writing. Roads to Yair’s opening conveys an in-depth representation of location as it was, rather than simply as it is at present. Khursheed’s combination of sensory contrasts, sharpened with her judicious use of alliteration, emphasize the hustle and bustle of the past, rather than the quiet, scenic place of calm it is now

outside the clatter of coal in clarty carts

to keep growth warm from April to dead winter

and the coalman’s clunking refractive

and the trainbound grapes packed soft in

Thomson’s own mossed crates

bound for London, and the braw shop

in Castle Street; outside

impossible to walk up that hill [.]

Scots words are scattered throughout the collection in such a way that they are (for the most part) immediately understandable to non-Scots readers. Serving as a reminder of the country to which these beautiful locations belong, they are also enhancing, imparting a real sense of pride in this heritage. Consider her use of “clarty” above; Khursheed places it where it would be difficult misinterpret. The use of the better known Scottish adjective “braw” is neatly tucked in between ‘London’ and ‘Castle Street’ – both English locations. This is a lovely touch. “St Boswell’s Fair”, however, is written in a pure form of Borders dialect which may well require the use of a Scots dictionary to untangle. Hefty old Scots words such as “cuddie” “chiel” and “quines” are relatively unknown to the average modern Scot. This challenge is no bad thing though, as it gives the collection linguistic diversity and texture.

Roads to Yair contains several running themes, probably one of the most important being that of change. The poet’s ability provides the reader with such strong immersive imagery of the past; furthermore, to be able to combine that so gracefully with contemporary imagery of the present in a single poem is extraordinary indeed. This is done particularly well in “Kelso library”

a row of written roses

picture book of posieswander amongst Southern Reporter

daffodils not lonelyat the computer quadrangle

a cloistered space with wordslike vines mapping

its Victorian wall.

Roads to Yair gives the genre of nature poetry a little something extra. It takes the reader on a journey through history as well as a passage through some of the most beautiful, tranquil locations of Scotland. Not only does it give the reader an awareness of these locations but also an insight into life, and how much it has changed over the centuries.

Angela Erskine

Leave a Reply