A Hatfield Mass

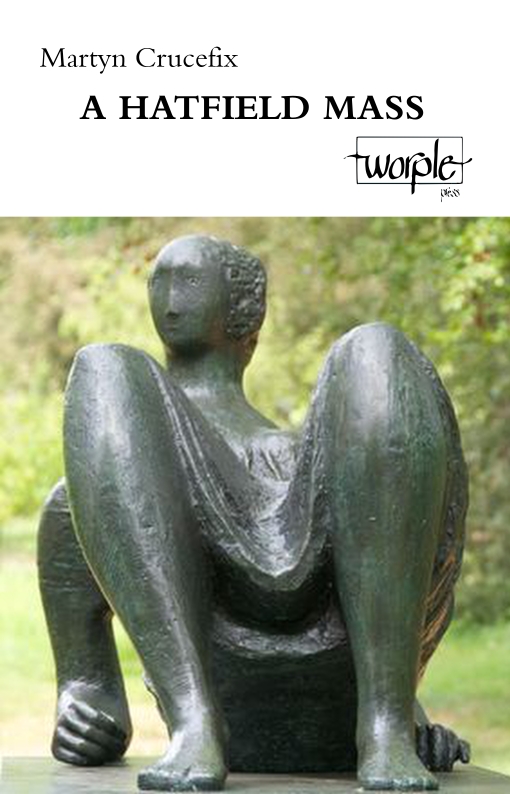

A Hatfield Mass is, in the main, a sequence of ekphrastic poems written after Martyn Crucefix’s visit to a Henry Moore sculpture exhibition in Hatfield House, Hertfordshire (Crucefix has assured many interviewers that this is, in fact, his real name). Crucefix’s sixth published poetry collection is thus structured: six poems inspired by six Moore sculptures, and a coda evoked by the anonymous German libretto of Bach’s cantata “Ich habe genug…” (BWV 82). All of the pieces referenced in this collection have been photographed and are available online to observe in tandem with these poems. Crucefix has gained significant recognition with his 2006 Popescu Prize-shortlisted translation of Rilke’s Duino Elegies but he has also won numerous accolades, including an Eric Gregory award and a Hawthornden Fellowship. In contrast to his study of past masters perhaps, Crucefix’s own poetry is concerned only with the perception and physicality of the immediate. These are not just sculptures but subjects: subjects which spark a plethora of perception.

A Hatfield Mass is, in the main, a sequence of ekphrastic poems written after Martyn Crucefix’s visit to a Henry Moore sculpture exhibition in Hatfield House, Hertfordshire (Crucefix has assured many interviewers that this is, in fact, his real name). Crucefix’s sixth published poetry collection is thus structured: six poems inspired by six Moore sculptures, and a coda evoked by the anonymous German libretto of Bach’s cantata “Ich habe genug…” (BWV 82). All of the pieces referenced in this collection have been photographed and are available online to observe in tandem with these poems. Crucefix has gained significant recognition with his 2006 Popescu Prize-shortlisted translation of Rilke’s Duino Elegies but he has also won numerous accolades, including an Eric Gregory award and a Hawthornden Fellowship. In contrast to his study of past masters perhaps, Crucefix’s own poetry is concerned only with the perception and physicality of the immediate. These are not just sculptures but subjects: subjects which spark a plethora of perception.

of taking note of the wren’s tick-ticking

the wren’s snicker animating the hedge

the chink of a blackbird in the holly treeas a trickle of dry gravel shifts beneath

the walking-pace of passing tyres [.]

“Taking note” of the details, hooking himself into the present moment, Crucefix observes these sculptures. Compared to the “passing tyres”, he is stationary; everything observed is rendered in the present tense. In something akin to Ezra Pound and his imagist poetry, Crucefix is intent on capturing a moment, though unlike Pound he seems unable resist the temptation of drawing conclusions in final lines such as, “if not more beautiful we grow more rich”.

Each poem has a subheading referencing a particular prayer sung at a Roman Catholic Mass. This overt nod to the Church gives Crucefix’s poetry a provocative aspect. Take his first poem “Large Totem Head”, with the subheading “Kyrie”, which comes from the first sung prayer of the Tridentine Mass. The poem draws inspiration from Moore’s bronze study of the same name. By the ninth line, Crucefix is calling back a memory where he breaks a fundamental taboo in the Roman Catholic faith.

to contemplate the ‘cyclops’ the ‘helmet head’

the sensation of my hand

where it strokes

my own not any other’s necktill the bolt disappearing down my spine —

it is only myself I am consoling [.]

This is arguably quite a graphic take on the statue, focusing as it does on a memory of masturbation – a large leap from a portrait which is far from explicit in its execution. These visceral words are as much a statement of the poet’s physical past as his creative present and current intent. Physicality is clear in his words;

beneath her elbow and her lovely arse

the carpet that soon must have burned

those little blushes across our skin[.]

He brings sex to the foreground of his poetry, intent on discarding past “forms” of the self and embracing the change and development wrought by experience.

Crucefix’s poetry is intimate and immediate, and also at times jarring in its open sexuality. Rather than fall prey to the obvious clichés of spiritual love, Crucefix bears the cross of sexuality in the face of oppressive stigmas, here manifested in Roman Catholic teaching, and lives, it seems, under another god: Aphrodite. In A Hatfield Mass, the poet holds his own sermon and prayer for where he believes salvation lies: the “engaging with and knowing of another’s body”. These are poems resolved to perceive and experience, events moving us from one circumstance to another, for by doing so “we grow more rich”.

Andrew Rogers

Leave a Reply