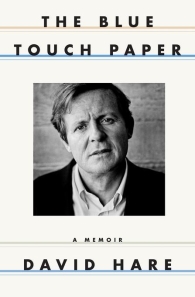

The Blue Touch Paper

“I had at the end of 1968 become literary manager of the Royal Court Theatre. This had happened largely by accident.” This kind of lucky accident often happened to playwright and director David Hare, who in a poll in 2000 by the National Theatre, had five plays selected in the top 100 and was 10th in the list of most selected playwrights.

“I had at the end of 1968 become literary manager of the Royal Court Theatre. This had happened largely by accident.” This kind of lucky accident often happened to playwright and director David Hare, who in a poll in 2000 by the National Theatre, had five plays selected in the top 100 and was 10th in the list of most selected playwrights.

His memoir tells the story of the first thirty years of his life and career. Raised by an absent father and often distant mother in Bexley-on-Sea, a judgemental and class conscious town, his academic abilities won him a scholarship to the religious boarding school Lancing College, a place where the boys had to swim naked with the swimming pool viewing gallery being the favoured place for visiting clergy to stand and pass the time. Hare’s time at this school deepened his feelings of being an observer. The correct way to behave did not come naturally as he thought it did for the other children, and he often found solace in film and theatre. Next was Cambridge, and Hare is often acerbic in his criticisms of its failings, remarking that, “The experience inoculated me for life against art which needs a framework of art theory to be understood.”

Reading David Hare’s memoir I was reminded of the saying that the harder you work, the luckier you are. His first short play, written in haste and out of necessity to fill a gap in the schedule of his touring theatre company Portable, was seen by Margaret Matheson (eventually to become his wife and mother to his three children as well as a prestigious drama producer in her own right) who was starting out as an agentThis led to a commission and the play Slag which was almost immediately offered a spot at the Royal Court. Unusually it had an all-female cast, “How could a dramatist not want to give half their stage time to half the human race? The regular testosterone-fuelled stage revolutions of the last fifty years have left me indifferent.” From this followed his apprenticeship as a playwright, where he was free to pursue his interests. It also enabled him to have all his early plays produced in relatively prestigious venues. The following scenario was typical: “One day my rock play Teeth ‘n’ Smiles was finished, next day it was scheduled. [at the Royal Court, ]”

The author recalls that “In the following twenty years [from 1968], more than seven hundred theatre companies were formed all over the UK, as if small-scale plays – confrontational, angry, direct – might somehow reach a gap in an audience’s concerns that nothing else was filling.” Not belonging to this world he depicts does make the book hard going occasionally; the reader is bombarded with a blizzard of actors, directors, managers, producers and agents, many whom are mentioned only once. There was the occasional feeling of reading journal entries with key names, dates and places but little surrounding explanation or insight. However, commentary and insight prevail, and he sometimes has a wonderful turn of phrase, as when describing Peter Jenkins the Guardian columnist “For me, his fluffy voice, whistling oblivious through archaic dentistry, was impossible to bear.”

Despite revelations of his marital breakdown and insights such as “I still hated myself after all and teaching played to a flaw in my character – an ability to dominate a situation by showing off”, and details such as his attendance of mille feuille pastry classes after the birth of his twins, I found Hare to be somewhat elusive in this book. I would have liked to have heard more of his personal views on the society and times he lived in, though this may more properly belong in another type of work. Although the book has its flaws, I am looking forward to reading the next volume and definitely want to read his plays.

Delia Gallagher

Leave a Reply