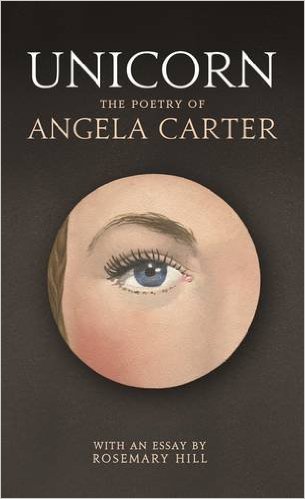

Unicorn: The Poetry of Angela Carter with an Essay by Rosemary Hill

Showcased as a “Stocking Filler” on a Waterstones table during the 2015 Christmas period, a distinctly, heavily-lashed female eye watches the reader discreetly through a peephole in an otherwise unassuming black cover. The latter hints at the erotic secrets within. This sexuality is often undertaken with pleasing irony to encompass the banal. Consider the virgin that is offered to bait the mythological unicorn:

She is raw and her breasts are like carrier

bags;

the only virgin to be had.

Undoubtedly unappealing, that carrier bag image also implies emptiness, mimicking the vacant vessel of the virgin, whose only purpose is to be filled. This then works well against the phallic imagery of the unicorn’s horn, the physicality of which Carter plays with in the interactive and instructional format of the poem’s 1963 publication in the magazine Vision, when she asks the reader to:

SEE THE HORN

(bend the tab, slit in slot

Marked ‘x’)

The image of a “fruit-cake” is a recurrent motif for female genitals and reproductive organs. The virgin’s “fruit cake” offers something which “ravens gorge on”, while the “the rich fruit-cake” of the pregnant cat in “My Cat in her First Spring” refers to unborn kittens inside. Both sexual and repulsive, the image unsettles the reader with the violence of the verb “gorges” in the first, then becomes homely in its function for the kittens within in the second, “where the wrinkled intuitions of her summer roses stir in their sleep”. This then corresponds to Carter’s future fixation with the atomisation of the female body, illustrating her poetry’s connection to the development of her later work.

However, only half of the volume is made up of Carter’s poems as the collection is then rounded off with three mini essays by Rosemary Hill. The first, titled “A Splinter in the Mind: The Poems of Angela Carter” refers to Carter’s remark that Walter de la Mare’s images “stick like a splinter in the mind”. Here, Hill’s analysis of the various poems catalogued serve as a welcome accompaniment. However, the final essay “Hair Fairies: The Prose of Angela Carter” seems somewhat out of place, it being the only essay which does not reference any of her poems, and the middle essay “Angry Men and Disgusting Girls: writing in the 1960s”, whilst providing some context for Carter as a writer, seems to fulfil no function other than boosting the page numbers. Hardly necessary, surely for such an intense collection.

It seems very unfortunate that Carter’s poetry has been neglected these last few decades, but this collection, with that striking cover, breathes new hope for her writing. It is always a gift to discover new little known work from writers you admire, and perhaps it’s a particular treat, if also bitter-sweet, when that gift is posthumous. As always her writing is sensual, the imagery vivid, violent and utterly delicious. Arguably her novels and short stories, written in fragments with their intense themes and captivating language seem more suited to poetry. I am at a complete loss as to why her poems have been overlooked for so long.

Kate McAuliffe

Leave a Reply