Geis

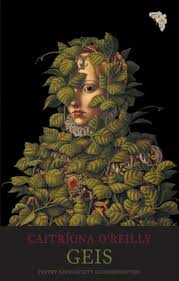

Book jackets are interesting indeed, ideally giving generously before even a word inside is seen. Madeline von Foerster’s arresting tempera panel Invasive Species II makes an apt introduction to the complex nature of Caitríona O’Reilly’s third collection, Geis. On the back cover, Patrick Crotty, in The Irish Times, praises The Nowhere Birds (Bloodaxe 2001), shortlisted for Best First Collection Forward Prize in 2001; amongst its accolades he describes that title as“The most startlingly accomplished debut collection by any Irish poet since Paul Muldoon’s New Weather in 1973.” So, no pressure then…

Book jackets are interesting indeed, ideally giving generously before even a word inside is seen. Madeline von Foerster’s arresting tempera panel Invasive Species II makes an apt introduction to the complex nature of Caitríona O’Reilly’s third collection, Geis. On the back cover, Patrick Crotty, in The Irish Times, praises The Nowhere Birds (Bloodaxe 2001), shortlisted for Best First Collection Forward Prize in 2001; amongst its accolades he describes that title as“The most startlingly accomplished debut collection by any Irish poet since Paul Muldoon’s New Weather in 1973.” So, no pressure then…

Challenging from its title on, Geis is an uncommon word, that back cover decoding “a word from Irish mythology meaning a supernatural taboo or injunction on behaviour.” Other sources label it both curse and gift. Significantly, almost invariably, a woman places the geasa on a man. Irish readers may be familiar with this from Cúchulainn.

Arguably, speaking and scrutinising the previously unspeakable in contemporary Irish life has been in the air of late; many fine creative voices are doing exactly that in Eire. Yet, for the most part, that is not the direction O’Reilly’s poetry takes. There is however a breath of that in “Viaticum” (the host given as the final unction in the Roman Catholic rite), the final part of a three-section poem “Island”, where there is a multiple-layering of meaning –

Forgetfulness

goes on with our clothes,

all the discreet lies.

O’Reilly’s Geis is wide-ranging in its appearance, poetic shapes and sources. For the poet’s needs, it may manifest itself in many ages, cultures, mythologies, philosophies and also in her own life, the latter to the point of the sharply confessional. Her examination of its purpose is thorough, finding a parallel otherness relevant to contemporary and continuing life. These guises and references are so encompassing that, in truth, it is hard to give a unified flavour here.

In “Polar”, for example, she versifies that very real bear, but challenges us to consider a creature not many of us meet in its natural setting. How real do we allow his presence, or more pertinently, his disappearance (the poet quotes from the U.S Geological Survey) to be?

A great absconded god of emptiness

[…]

Who will bury him like the Chukchi,

his huge head indicating true north,

amid libations and the pouring out of oil?

This perhaps slightly parallels the Gillian Clarke poem of the same name, but here there is an environmental cry at the world’s capacity to ignore science, ambling thus to catastrophe. This theme runs through many of these poems. The dangerous complicity of silence and the failure to act is laid bare.

Actual mythology is also present, and possibly its scope is best served by her encapsulating title “Comparative Mythography”, offering the haunting thought “Each day brings less, now, / to believe.” So many diverse cultures and beliefs… but O’Reilly does not stop there. In a clever use of the form’s slip-slide imagery and hypnotic refrains in “The Man with No Name as Vital Principle: A Ghazal”, we leave behind Mexican gods, Namibian considerations, the Nordic, Pliny, the Biblical, the family history and many, many more to face …Clint Eastwood. Certainly, the poem works, but perhaps that unlikely spaghetti-Westerner’s presence flags up a problem for readers.

“Ovum” opens the collection, wonderfully stringing words and etymologies as a marker for what is to come: sustained multiplicity, learning and feminist understanding. However, the nature of all of these poems with their opulent, sometimes obscure references, their essential duality (at the very least), and their inherent musicality in loved language means the Geis will prove a protracted read for most. That in itself is fine. Returning to that Muldoon gauntlet on the jacket, and not having read every Irish poet’s debut since 1973, I cannot agree or disagree. Yet I suspect what is offered here is so great that O’Reilly might have composed several collections rather than give such a dense singleton.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply