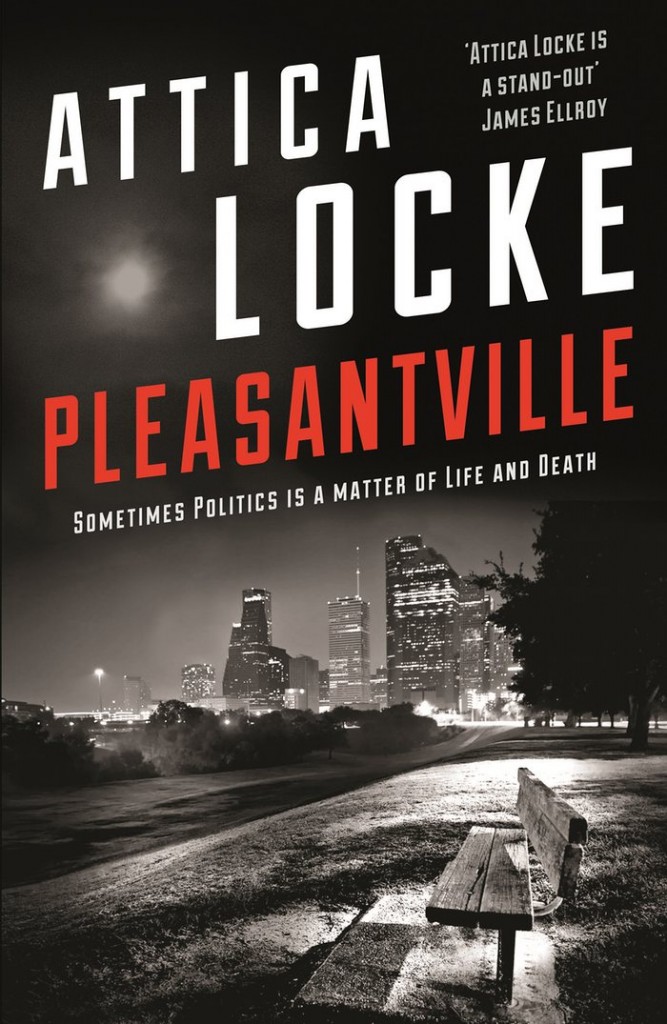

Pleasantville (Longlisted for the 2016 Baileys Prize)

A graduate of Northwestern University, Attica Locke was a Fellow at the Sundance Institute’s Feature Filmmakers Lab. She has been a scriptwriter for Paramount, Warner Bros, Twentieth Century Fox, HBO and Dreamworks, and is currently a writer and producer on the Fox drama Empire. Locke’s focus is African-American cultural and political history and her 2010 debut novel, Black Water Rising, was shortlisted for the Orange Prize and nominated for an Edgar Award, an NAACP Image Award and a Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Her second, The Cutting Season, was the 2013 winner of the Ernest Gaines Award for Literary Excellence.

A graduate of Northwestern University, Attica Locke was a Fellow at the Sundance Institute’s Feature Filmmakers Lab. She has been a scriptwriter for Paramount, Warner Bros, Twentieth Century Fox, HBO and Dreamworks, and is currently a writer and producer on the Fox drama Empire. Locke’s focus is African-American cultural and political history and her 2010 debut novel, Black Water Rising, was shortlisted for the Orange Prize and nominated for an Edgar Award, an NAACP Image Award and a Los Angeles Times Book Prize. Her second, The Cutting Season, was the 2013 winner of the Ernest Gaines Award for Literary Excellence.

Pleasantville, her third novel, is set in 1996 America. Bill Clinton has been re-elected to the White House and elections for mayor are looming in Houston. Campaigning is focused on the predominantly African-American neighbourhood of Pleasantville, where black voting power has swung many close polls. Axel Hathorne, son of Pleasantville’s founder Sam Hathorne, seems set to become Houston’s first black mayor. Then, a girl goes missing. When her body is found, Axel’s nephew and campaign manager is charged with her murder. Local lawyer Jay Porter, a widower struggling to raise a young son and teenage daughter, is called upon to represent Axel’s nephew.Though Locke has fictionalised some of its history and geography, Pleasantville is a real neighbourhood. Her omniscient voice makes the setting compelling, delivering cinematic views of the locale.

Politics, murder and family tragedy are the main threads running through this complex narrative. Locke successfully pulls these threads together giving an historical perspective on this black community’s creation, its evolution, and its future, as well as the political future of America. Told in three parts, the first introduces the missing girl, Alicia Nowell, and a multitude of other characters, any one of whom might be guilty of her demise. In the second part, Porter encounters many obstacles as he builds his client’s defence which leads, in the third part, to the novel’s climax, a set-piece courtroom drama that echoes the writing of John Grisham. However, in my view, Locke’s depiction is neither as vivid nor as dramatically powerful.

Crime writing depends on intricate plotting to keep the reader guessing. Locke provides all the conventional signposts; finding the body, calling the police, telling the parents, making the arrest. However, I felt these elements took second place to the overarching political theme of the novel and, unfortunately, I identified the culprit long before the climactic end.

A good murder mystery also needs multiple characters and although Locke provides these in abundance, I found few discernible differences between them. Locke is an experienced scriptwriter working in film and television so I expected her dialogue, encompassing character action, to be natural and full of imagery. Indeed, in this she did not disappoint. However, individual speech patterns that might also have helped define the characters were not present which left me feeling less than engaged.

Locke’s main emphasis seems to be the corruption of those in political power – whether black or white. As she said in an interview in the Los Angeles Times in 2015:

I think I get away with a lot of political stuff because

of the presence of a dead body. If you have familiar signposts

along the way […] readers get comfortable, and then you can

slide in all this other material.

I wanted to be excited by this book, to feel Locke’s passion for her subject. However, I was left feeling flat at the end of the book. I wasn’t sure if this was crime fiction, or political thriller. In the end it was both but, unfortunately, excelled at neither.

Lesley Holmes

I’m in accord with this excellent review. I started with Black Water Rising and found the double layer plot of racial politics and a murder mystery was like reading two novels at once. The balance between the two themes is heavily weighted towards the political arena and the dock workers’ troubles so that the murder becomes a minor strand, brushed under the carpet, almost hidden behind the narrative barrier of politics and policy, of black and white. The sentence structure drove me mad – I started counted the number of sentences that started ‘Jay….’ even when there was no other character in sight. Did the author not know about pronouns? Who edited this novel?

Pleasantville is somewhat better balanced but again two genres – politics and murder – are confusedly intertwined, leaving me wanting to tease them apart and to give my full attention to each. And in this novel we have a third layer of family tragedy in the form of a death from cancer. It’s too much. I found it hard to care much or to feel emotionally involved with any of the characters. It’s a multi-layered story offered at arm’s length.

So why the hype and prizes?