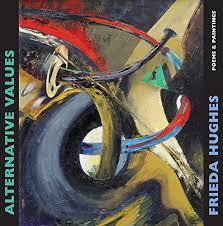

Alternative Values: Poems and Paintings

Everybody deserves recognition for their creative achievements, unshadowed by backstories and illustrious family comparisons. Rightly, this courageous painter-poet has long been outspoken, criticising those choosing to play with her biography to suit their own ends. The press release is wisely oblique on this aspect. I turned away from the room’s elephant.

Everybody deserves recognition for their creative achievements, unshadowed by backstories and illustrious family comparisons. Rightly, this courageous painter-poet has long been outspoken, criticising those choosing to play with her biography to suit their own ends. The press release is wisely oblique on this aspect. I turned away from the room’s elephant.

Frieda Hughes is probably better known as a visual artist than as a poet. Nonetheless, she has written several children’s books, has been a Forward Prize judge; this is her fifth full collection published by Bloodaxe. Alternative Values marks her first time Hughes has twinned those “two disciplines that are the driving forces” in her life. An accompanying exhibition ran at the Belgravia Gallery in October.

Generous in its larger than usual for Bloodaxe format and full-colour presentation, Alternative Values’ thumbnail index of images reads as much like a gallery catalogue as a poetry collection. Neither discipline predominates, and her text is neither ekphrastic, nor are her images illustrative; both forms evolve in tandem, continuing to interact in print.

Some of the pairings face one another; all share titles. In the case of (mostly) shorter poems, the text is superimposed on a predetermined space. The index gives the uncropped images sans text. Hughes’ visual work is vibrant and painterly, her colour holding traces of her many years in Australia. She describes her paintings as “abstract”, but in the dynamism in this work is perhaps more semi-abstract, especially in relation to the text. Whilst not fully representational, shapes colours and symbols emerge, easily accessible. On the whole, her paintings possess an energy and a vivacious quality that her poems often lack.

Consider some of these couplets (each a full poem), starting with the opening “Love” :

Love is not always about people

Nor do people always find love.

Midway in the collection, “Planning Ahead”:

What we become tomorrow

Is because of the choice we make today.

Later, “Free Speech”:

You are not free to speak your mind

If your opinion does not comply.

Pleasing enough on the page, and they might make appealing cards, but an unsettling thought needles – even slapped on these powerful images, are these more than aphorisms? They are not typographically adventurous, being set conventionally on a (usually beige rectangular and slightly sticking-plaster) prepared space, so at this point there is no sparking connection happening.

Some of her longer poems are painterly indeed, visually evocative and textured in their narrative:

My father photographing us,

Bundled in my mother’s arms,

All his eggs in one basket.

That elephant is unavoidable. So many of these poems are openly autobiographical.

We borrow people, by blood or birth, marriage or friendship

but they are not ours to keep:

We do not possess them – we have no rights,

Not even in partnership or parenthood[…]

And sometimes death.

Irrefutably so, as alas Hughes is better qualified than most to know. No-one has a right to invade that space, but this review must ask – do these work as poems? Do these lines show, or do they overtell? Do they state the obvious, obviously?

Further, when we are offered lines like “My father is made poet laureate”, “As she left us bread and milk before/She shut us in and Sellotaped our door?” and when The Bell Jar is named, that elephant fattens uncomfortably. While this is Hughes’ territory to investigate (or not) as arguably only she has the right, no-one else being quite so qualified to speak to that pain, yet we must ask, are these poems all they should be?

Her paintings speak more strongly and hopefully. Of her poems, there are those dealing more subtly yet powerfully with her brother’s death that lift the collection, and I would love to see more like her playful adult and child-aware “Recipe for an Exploding Cat”; however there is much here to feed the very industry Hughes’ despises. I am left with great disquiet.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply