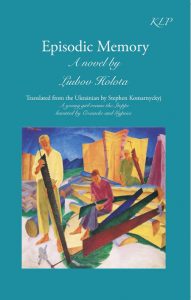

Episodic Memory

A journalist and published poet, Ukrainian writer Liubov Holota became a Shevchenko Laureate after receiving the Shevchenko Premier for her debut novel Episodic Memory. Framed by the forty day vigil for her dead mother, the novel sets up vignettes of one woman’s childhood in the Ukrainian Steppe in the 1950s. Holota’s novel is fully transportive in its sense of place, detailing every setting with a lyrical poeticism that Stephen Komarnyckyj does not lose in his translation of the work.

A journalist and published poet, Ukrainian writer Liubov Holota became a Shevchenko Laureate after receiving the Shevchenko Premier for her debut novel Episodic Memory. Framed by the forty day vigil for her dead mother, the novel sets up vignettes of one woman’s childhood in the Ukrainian Steppe in the 1950s. Holota’s novel is fully transportive in its sense of place, detailing every setting with a lyrical poeticism that Stephen Komarnyckyj does not lose in his translation of the work.

The importance of memory is inescapable in Holota’s novel, as she recaptures the past, fearful that “[w]e are becoming impoverished in our watchfulness of this world, in our recollections of sounds, colours, fragrances.” This emphasis on the sensory aspect of memory is highlighted in the vivid sense of place Holota creates in this fictional memoir:

[…] a thick frost gripped the orchards and homesteads of Lyubymivka with such a fabulous beauty that every twig, every stalk of every weed, and the grass on the surrounding pasture, exhaled its living moisture to the last drop. It played with the sombre colours of autumn’s sorrow and the dazzling whiteness of crystallised ice and its small, innocent celestial flowers.

This is a perfect example of Holota’s use of rich descriptions throughout the novel, as she lists every detail, thus recreating memory as a type of photograph one can examine at will. This is also indicated in the motif of the mirrored wardrobe, in which the girl watches her reflected self and later thinks back on all the events the mirror has witnessed and the memories it preserves: “Episodic memory did not require these long lived-in things which she had grown out of long ago and that her parents, for some reason, tenaciously preserved in this wardrobe.”

In an interview with Kalyan Press, Holota commented on her application of American psychologist Tulving’s theory of Episodic Memory as a metaphor for the disintegration of communal narratives under the impact of globalisation. Her writing immerses the reader in the sights and sounds of a disappearing world by describing the somewhat mundane daily life of a young girl in Soviet Ukraine.

Language is consequently also key to Holota’s novel, as that is the main vessel for retaining memory, and this element was threatened by the favouring of the Russian language over Ukrainian by the former occupiers. However, this does lead to the question of why the novel was translated into English. Translation is an indication of globalisation and reduces the original writing by finding only an English equivalent. It is also notable that, while a tremendous feat, some of the translated vocabulary is too clunky in its exactness, pulling the reader from the story, as for example when the horses are referred to as “the collective farm’s equine population…”

In addition, much of the novel seems to be written in an overly elaborate style, which becomes too detailed in the actions of the heroine, for example as she “slowly made the bed, covering it with the old sheet, fluffing up the pillow and placing it vertically on the bed…” However, this slow pacing perfectly suits the rustic and humble life of the girl on the Steppe and builds up to the rewarding and poetic insight “…where she had grown up and where her father had been lulled to death by sleep.”

Holota’s novel gently dips in and out of memory, allowing glimpses into an Edenic and vanished world, which she graciously shares with us. Perhaps somewhat overwritten and translated too literally, Episodic Memory is nevertheless a fascinating study of place: of the sights, sounds, smells, tastes and feeling of a place which now only exists in memory, justifiably lending itself to a slow deliberation of events.

Kate McAuliffe

Leave a Reply