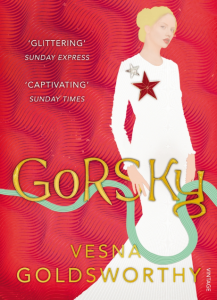

Gorsky

Sometimes there is irony in a book’s appearance and format. This ‘Little Red Book’ is not a collection of quotes by Chairman Mao, but a novel that echoes the great American jazz-age classic, The Great Gatsby. The (anti?) hero in this case is Roman Gorsky, a billionaire Russian oligarch who has settled in London, during the early 2000s.

Sometimes there is irony in a book’s appearance and format. This ‘Little Red Book’ is not a collection of quotes by Chairman Mao, but a novel that echoes the great American jazz-age classic, The Great Gatsby. The (anti?) hero in this case is Roman Gorsky, a billionaire Russian oligarch who has settled in London, during the early 2000s.

Vesna Goldsworthy was born in Belgrade in 1961. She has previously published a memoir, a cultural history of the Balkans and a prize-winning poetry collection, The Angel of Salonika. She is Professor of Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia and has lived in London since 1986.

Nikola Kimovic – Nick – is the narrator, through whose eyes the narrative unfolds. He is a Serb who escaped to the West from the war-torn Balkan states in the early 90s. Nick works in Fynch’s, a rather run-down bookshop in Chelsea. His world is overturned when he is commissioned by the billionaire Gorsky to curate a library for his palatial new London home. This commission opens a window for Nick into the decadent world of the super-rich.

Natalia Summerscale, unknown to Nick, is Gorsky’s lost love. She is a Russian émigré married to a wealthy Englishman, Tom, who is just as arrogant as his counterpart in Gatsby. Their daughter Daisy seems to embody the untouchability of her parents’ wealth and apparent security. When Natalia’s interest in contemporary Russian Art leads her to Fynch’s, Nick becomes fascinated by her poise and elegance, worshipping her from a distance.

These allusions to Gatsby, and some less obvious references to great Russian literature, might render Gorsky a bland pastiche of Fitzgerald’s best known work. But Goldsworthy reworks the Gatsby narrative instead to create a backdrop of the unrestrained accumulation of wealth in the aftermath of from the collapse of the Soviet Union, leading to the rise of the ‘Kleptocracy’ – a term that describes the economy of ex-Soviet states, where wholesale asset-stripping of the state machinery was often carried out by the same individuals who had been in positions of power in the Communist party. This great shift from public to private wealth was mirrored in the West by the development of rampant unregulated speculation on the London stock market prior to – and since- the banking crisis. Tom Summerscale, it is implied, is one of its beneficiaries.

Who is Gorsky? No-one knows how his fabulous wealth was created. Speculation abounds that he made his billions in the arms trade or the Russian mafia. He seems to have been present in the Balkans during the war, but all he reveals is that he fell in love with Natalia when she was nineteen and has waited for her since. The author and narrator resist passing judgement on him, allowing the reader to reach her/his own conclusions.

Nick’s character is extremely well drawn, though he tests the limits of credibility with his non-attachment to the super-wealthy world he is invited to inhabit. He allows the experience of luxury to flow through him as passively as a Zen monk might. His only vanity lies in curating the finest library for Gorsky, in a vicarious attempt to seduce Natalia via his choice of books.

Just as Nick is dazed by Gorsky, Natalia and the impossibly glittering world he finds himself in, so the reader is seduced by Goldsworthy’s lightness of touch as she paints a picture of a world that appears beautiful, but where shadows hide something murky, foreboding. Her use of hyperbole to describe fabulous interiors is both comic and highly effective. Of the entrance hall of Natalia’s mansion, Nick exudes “the softest, whitest pile imaginable stretched ahead of me. Behind the double front door it covered acres of the vast lobby, lit by a huge chandelier…..It was soundproofed so well that I could hear my own heartbeat.” Yet Nick can see that neither Gorsky nor Natalia have been made happy by their huge wealth. In Gorsky, Goldsworthy resists the creation of a morality tale, but she leaves the reader meditating on love and loss.

Jenny Gorrod

Leave a Reply