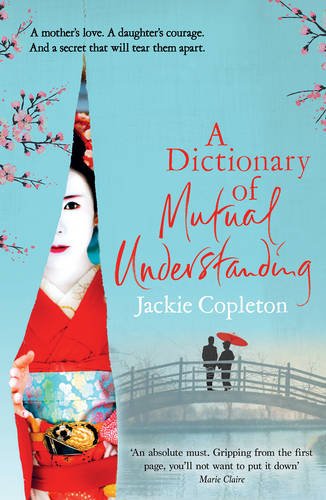

A Dictionary of Mutual Understanding

Jackie Copleton’s first novel is ambitious in its themes and in the spread of history it encompasses: A Dictionary of Mutual Understanding is set mainly in Nagasaki across the years before, during and after the dropping of the atomic bomb. The plot revolves around Amaterasu, a mother and grandmother, whose desperate search to find her family after the devastation wreaked by the bomb and the consequent loss of hope and bereavement turns into a revelation of not just her story but also the stories of her daughter Yuko, her grandson Hideo, and of the physician Sato, once a good friend of her husband. The novel examines the secrets and lies which divide them all, and which threaten to snap the slender threads which may yet hold them all together.

Jackie Copleton’s first novel is ambitious in its themes and in the spread of history it encompasses: A Dictionary of Mutual Understanding is set mainly in Nagasaki across the years before, during and after the dropping of the atomic bomb. The plot revolves around Amaterasu, a mother and grandmother, whose desperate search to find her family after the devastation wreaked by the bomb and the consequent loss of hope and bereavement turns into a revelation of not just her story but also the stories of her daughter Yuko, her grandson Hideo, and of the physician Sato, once a good friend of her husband. The novel examines the secrets and lies which divide them all, and which threaten to snap the slender threads which may yet hold them all together.

The passage of time and the interpretation of historical events both universal and personal are major themes in A Dictionary of Mutual Understanding, and the narrative jumps around in time from Amaterasu’s youth in the early 20th Century right up until 1984, where its present narrative voice is set, although I had to do a bit of detective work with dates and ages to work that out! It does seem rather a contrived coincidence that one of the enduring mysteries of the novel, which so much of the current action is bound by, could be easily resolved by a simple DNA test which was not actually possible until 1986.

Each chapter starts with a section from a book which Amaterasu and her husband Kenzo purchase after their emigration to the USA, the titular Dictionary of Mutual Understanding. The extract at the head of each chapter is clearly meant to foreshadow the content which follows, but this motif seems overdone, especially as the wording in these descriptions seems to be written in a deliberately clunky English translation of Japanese, and I often found myself skipping these parts as they muddied the text which followed rather than actually enhancing it. So now, onto all the good things I have to say, which greatly outnumber these latter minor niggles.

This novel did everything I want a book on my “reading for pleasure” shelf to do; it has strong and believable characters who are both passionate and flawed, it has a complex set of interlinking plotlines which dance seamlessly to and fro in time, and it has sections of narrative which are edifying in their content, revealing intriguing details about Japanese culture and the history of the country during wartime, powerfully and vividly described. As Amaterasu says of the Nagasaki Atom Bomb exploding;

There can be no word for what we heard that day. There must never be. To give this sound a name might mean it could happen again. What could capture the roar of every thunderstorm you might have heard, every avalanche and volcano and tsunami that you might have seen tear across the land, every city consumed by flames and waves and winds? Never find the language for such an agony of noise and the silence that followed.

One of the main themes of the novel is the power of love and sexual attraction and the way in which it can change the course of lives in an instant. The author does a fine-handed job in her treatment of sex scenes – always difficult to do well. She also handles the large amount of historical detail of the characters’ lives in a measured way; never does it become overtly expositional. The denouement at the end of the novel is what the reader feels has to happen right from the start, but it is skilfully arrived at, and in between we have felt the characters’ pain and sometimes identified with the tragedy of their lives at the most human of levels. This is a compelling and convincing work of art.

Lorna Hanlon

Leave a Reply