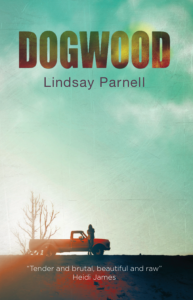

Dogwood

Lindsay Parnell’s debut novel Dogwood is not for the faint hearted. The novel begins with the main protagonist, Harper, writing a letter to her younger brother Job telling him about the execution of Tara Hackett, a murderer whom she met in prison. The explicit descriptions of violence and sheer horror presented serve as a warning. Having chosen to continue, the reader is swept into a world of drugs, sex and alcohol accentuated with violence.

Lindsay Parnell’s debut novel Dogwood is not for the faint hearted. The novel begins with the main protagonist, Harper, writing a letter to her younger brother Job telling him about the execution of Tara Hackett, a murderer whom she met in prison. The explicit descriptions of violence and sheer horror presented serve as a warning. Having chosen to continue, the reader is swept into a world of drugs, sex and alcohol accentuated with violence.

The sisterhood between Harper and her childhood friends Caro and Collier is introduced through flashback sequences separated from the italicised letters to Job by titles that reveal their ages respectively, allowing the reader to understand how they became who they are. It is this disjointed structure of the novel that almost forces one to keep reading, never being able to put the book down. The fragmented story, pieced together from snippets of brutality and abuse, offers no light relief.

The relationship between the girls initially appears to be simply an innocent childhood friendship but this deteriorates throughout the novel even as they continue to cling to one another. Presented with no reliable authority figure, the three are left to fare for themselves and they encourage one another in their destructive habits, which is what ultimately led to Harper’s incarceration.

“I ache for the girls we could have been, Caro and me an Collier, ache for the girls we were too afraid to be.”

The reader cannot help but love these flawed characters fighting through the stagnation and decay of their world. Caro and Collier, two vastly different and equally damaged girls, seem at times both pitiable and beyond redemption. It is in fact this element that makes Dogwood unique. Parnell’s ability to write perfectly human characters that you simultaneously love and abhor keeps the reader hooked throughout the book, and no matter how much you wish to save them from themselves, there is nothing more to do than to watch in horror as the three girls destroy one another.

The complexity of the writing style also contributes to the overall effectiveness of the novel. The consistent dialect and jolting style of writing only adds to the jaggedness of the world the characters live in, enabling the reader to experience almost too realistically what the novel is about. This, when combined with the run-on sentences that form nigh incoherent paragraphs portraying Harper’s confusion, creates a unique and fresh voice, although it does take some getting used to initially.

Christianity and religion also play a major role in the novel and are repeatedly referenced by the characters who, despite their apparent belief in salvation, seem unable to truly embrace it before it is too late. “Read the Bible to your little girl and give her a new name. Save her or let her be damned” Harper writes to Job at the end of the novel. The initially paradoxical words, however, make perfect sense when examined in the context of the rest of the novel. There is a strong theme suggesting that Harper, Caro and Collier could have been saved by religion, or simply by having a parental figure to show them the right way. Thus Harper’s plea to Job becomes an important one; she is asking him to save his daughter from becoming her.

“Because Caro and me and Collier are the girls nobody remembers.” These are the last words of the novel, but the truth is that if you make it to the end of the novel there is no way to forget any of the three girls. They stay with you, the weight of their stories a constant reminder of what Parnell expertly portrays: just how easy it is to fly too close to hell.

Anne Härkönen

Leave a Reply