An Adrian Tomine Double Bill

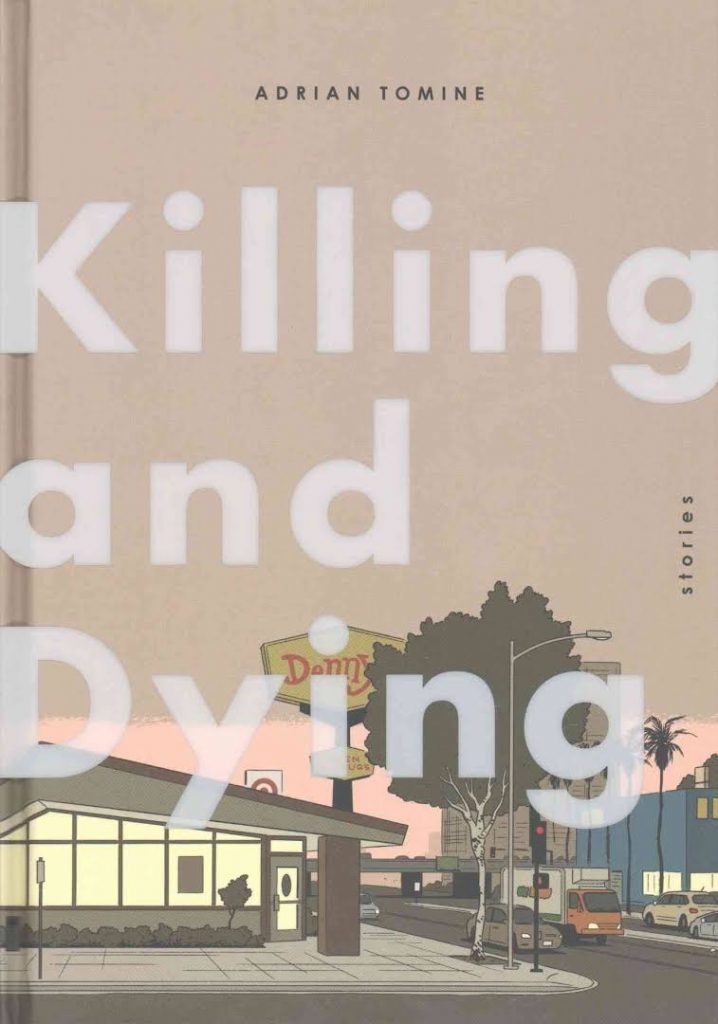

Killing and Dying (Faber & Faber, 2015); hbk, £14.99

New York Drawings,

(Faber & Faber, 2012); pbk, £14.99

In the endnotes of New York Drawings, Adrian Tomine asserts that he is a cartoonist, “not just an illustrator.” However, it is precisely that tension between those two artistic identities that define Tomine’s work. Indeed, his two most recent publications, New York Drawings and Killing and Dying, emphasise his versatility, demonstrating that, in spite of what he may claim, Tomine is just as capable an illustrator as he is a cartoonist.

In the endnotes of New York Drawings, Adrian Tomine asserts that he is a cartoonist, “not just an illustrator.” However, it is precisely that tension between those two artistic identities that define Tomine’s work. Indeed, his two most recent publications, New York Drawings and Killing and Dying, emphasise his versatility, demonstrating that, in spite of what he may claim, Tomine is just as capable an illustrator as he is a cartoonist.

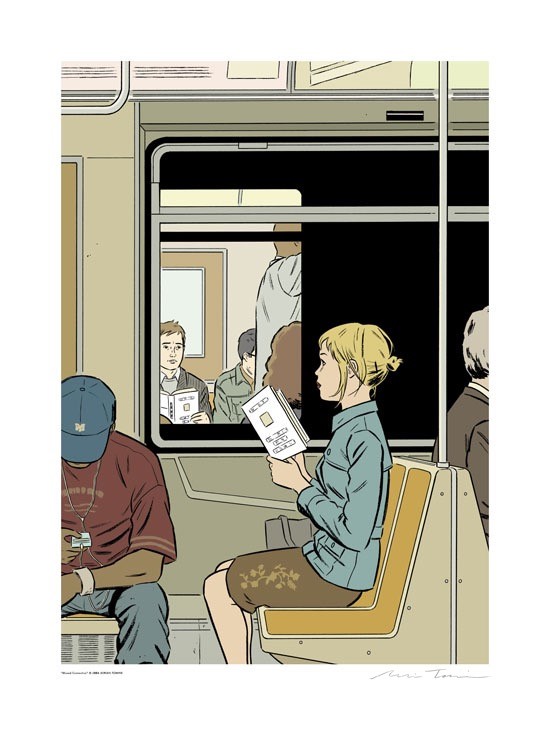

New York Drawings itself is a combination of illustrations and comics, collecting a mix of published work (much of which first appeared in The New Yorker) and personal sketches created after Tomine moved to New York in 2004. The bulk of the collection is made up of covers and illustrations used in articles and film reviews, but even in these decidedly non-narrative instances, Tomine demonstrates a skill for storytelling. The most striking example is “Missed Connection”  which was first published on the cover of the 8 November, 2004 issue of The New Yorker.

which was first published on the cover of the 8 November, 2004 issue of The New Yorker.

Tomine sites the piece as his “best-known drawing,” and it’s easy to see why: the whiff of a narrative implied by this single image is electrifying. Tommie credits his editor, Françoise Mouly, for insisting that the image “contain at least a kernel of a story,” but his skill at capturing a story in a single moment permeates all of his work in New York Drawings.

The personal sketches included in the collection suggest that Tomine’s narrative prowess stems from his power of observation. Virtually every sketch, drawn from real life models of fellow subway passengers and pedestrians, includes hastily jotted notes describing his subjects, from “exhaling loudly” to “his mouth moved as if he was chewing”.

New York Drawings does contain a few comics, mostly semi-autobiographical accounts of Tomine’s life in New York, but Killing and Dying, a comic-as-short-story collection, demonstrates his range as a cartoonist much more thoroughly. Loosely addressing tragic themes (although not quite as tragic as the title suggests), the stories are so diverse in terms of style and tone that it may be best to highlight them individually.

New York Drawings does contain a few comics, mostly semi-autobiographical accounts of Tomine’s life in New York, but Killing and Dying, a comic-as-short-story collection, demonstrates his range as a cartoonist much more thoroughly. Loosely addressing tragic themes (although not quite as tragic as the title suggests), the stories are so diverse in terms of style and tone that it may be best to highlight them individually.

The first, “A Brief History of the Art Form Known as ‘Hortisculpture’”, follows a gardener-cum-artist on his flagging quest to convince the world of the value of his sculptural flower pots. In this case, Tomine embraces the conventions of a newspaper comic strip, telling the story in four-panel episodes, interspersed with the occasional longer “Sunday” strip in full colour. The effect accentuates the passing of time, as the protagonist and his family age six years in under 20 pages. The trappings of a gag-a-day strip also add a subversive element to the existential crises at the centre of the story, building to a final punchline several shades darker than any newspaper comic would ever print.

The second, “Amber Sweet,” details the story of a young woman who discovers that she bears a striking resemblance to a popular porn star. It serves as an intriguing indictment of the way female sexuality is approached in America — particularly in the L.A. area, where the story is set — but the real power lies in its framing. The third story, “Go Owls,” follows a pair of co-dependent addicts in their struggle to form a life together. Tomine establishes their downward spiral with remarkable clarity, rendering their world in a desaturated pallor. Their inevitable crash is broadcast early on, but with so much detailing of the couple’s disfunction, it’s difficult to say if the conclusion is ultimately destructive or liberating.

The fourth story, “Translated, from the Japanese,” represents another stylistic departure, as an epistolary text combines with first-person perspective shots to create the effect of a long-forgotten memory. Here, those powers of observation Tomine honed in his sketchbook pieces are on full display, capturing entire locations in snapshots of simple, telling details. The fifth story, the one from which this collection gets its title, sounds a bit more tragic than it ultimately is. It does feature a death, but the killing and dying refers to standup comedy. More specifically, it refers to a young, socially awkward girl’s attempts at standup; one successful performance before her mother’s death, and another terrible one afterwards. The drama stems from her father’s sympathetic — and perhaps misplaced — sense of embarrassment. Tomine’s deft hand at subtext manages to wring a remarkably subtle story out of these heady themes. Indeed, Tomine leaves the key moments, including the mother’s death, off the page, punctuating the story with ambiguous white space.

The final story, “Intruders” follows a lonely veteran as he finds some catharsis in breaking into the apartment he once shared with his ex-wife. He’s not there to steal anything, he just finds comfort in being in that space again, which leads him to a routine of breaking in every day while the current tenant is at work. The sense of danger that permeates his first break-in slowly dissipates until he apprehends another intruder breaking into the same apartment. It brings the story to the same uncertain ending that pervades the entire collection, allowing the question of “what’s next?” to hang in the air long after the book is closed.

Either one of these books illustrates a range that would be enviable in any artist, but taken together they cement Tomine’s reputation as one of the most gifted cartoonists of his generation. These books may appeal to different audiences — New York Drawings is a coffee table art book, while Killing and Dying is a short story collection focused on the banalities of modern life — but I suspect everyone should find something to love in both.

Drew Baumgartner

Leave a Reply