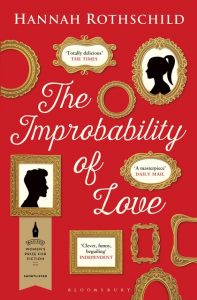

The Improbability of Love

There are two major problems with The Improbability of Love. The first is that it’s just too long and the second is that it’s dull. The large cast of characters and their sub-plots are exhausting. There is an ensemble cast of at least eighteen different characters, each with a section dedicated to their point of view, but only four of them are essential to the progression of the plot. Half-way through the book I stopped caring who anybody was or why they were buying £100,000 rugs, wearing 3-foot-tall wigs or worrying about their children attending Eton. This was also around about the time that I realised that most of the secondary characters could be cut and the story would plod along just fine, if a little more quickly and with a tighter narrative. The two central characters – Annie, a downtrodden, aspiring chef who buys a lost masterpiece in a junk shop and Rebecca, the CEO of an international art dealership, who is searching for the painting – both have complex personalities, and are driven by their pasts, their families and a desire for success and control in their lives. Yet neither of them has any real depth. The narrator diminishes so much of the emotive punch by summarising for the reader instead of letting characters reveal themselves in the dialogue;

There are two major problems with The Improbability of Love. The first is that it’s just too long and the second is that it’s dull. The large cast of characters and their sub-plots are exhausting. There is an ensemble cast of at least eighteen different characters, each with a section dedicated to their point of view, but only four of them are essential to the progression of the plot. Half-way through the book I stopped caring who anybody was or why they were buying £100,000 rugs, wearing 3-foot-tall wigs or worrying about their children attending Eton. This was also around about the time that I realised that most of the secondary characters could be cut and the story would plod along just fine, if a little more quickly and with a tighter narrative. The two central characters – Annie, a downtrodden, aspiring chef who buys a lost masterpiece in a junk shop and Rebecca, the CEO of an international art dealership, who is searching for the painting – both have complex personalities, and are driven by their pasts, their families and a desire for success and control in their lives. Yet neither of them has any real depth. The narrator diminishes so much of the emotive punch by summarising for the reader instead of letting characters reveal themselves in the dialogue;

Evie though she had gone mad (Thought? Anne nearly laughed), but although the flat was very tidy, things weren’t quite the same (Were you seeing double?).

The characters and scenes lack life, leaving the reader slogging through pages and pages of lacklustre story which is a real shame because, considering the novel touches on issues such as the principles of value, the Holocaust, and alcoholism, it has so much potential to be good.

Perhaps the most interesting and unusual aspect of the novel is the fourth-wall-breaking painting. This is a device I have mixed feelings about. Having the object which is at the centre of the novel directly address the reader is either brilliant or ridiculous. Either way, it fails to live up to it’s potential. The painting speaks in the parody of a 16th century French courtesan, by way of a particularly catty EastEnders character, and the jumble of her Aristocratic-French/Coarse-Londoner diction, which is initially amusing, quickly starts to grate;

This did not lesson my humiliation when produced like a lapin out of chapeau and manhandled by a drunken floozy, nearly arrested, shoved back in plastique and bundled back out into the cold.

In-keeping with her shallow, self-absorbed persona, her insights into the mind of her creator, the secret lives of her owners and key moments of European history are superficial. I feel like she was either criminally underused or utterly pointless. Perhaps Rothschild should have used the painting in the stead of the omniscient narrator. A conspiratorial narrator could have created a greater degree of intimacy with the reader and built some sorely needed tension in the novel. Since the story is told in retrospect it’s not unreasonable that the painting would have access to the thoughts and feelings of the characters. Besides, I would’ve been quite prepared to suspend belief regarding the all-seeing powers of a self-aware masterpiece who could enrich scenes with her three hundred years of experience and knowledge, especially if it was funny.

The Improbability of Love is a confused muddle of mystery novel, improbable romance, and slapstick comedy. Rothschild has an obvious familiarity with the art world and I suspect that perhaps she tried to write a grand satire, it would certainly explain her flamboyant but hollow characters and the implausible situations they find themselves in. If so, perhaps I am just too far removed from that milieu to appreciate it, otherwise it lacks the suspense of a successful mystery novel, the emotion of any engaging romance, or the humour to be a considered a comedy.

Paula Lyttle

I am inclined to agree with the critic. Too long and side characters aren’t that interesting