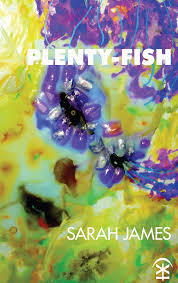

Plenty-fish

Sarah James’ Plenty-fish cannot be gulped in one go, slipping as it does magnificently around in the imagination, never quite solidly poetry, but fleshy and fresh. The seventy-one-piece collection contains poems of varying lengths – all semi-anecdotal and detailed accounts of everyday life. As a graduate in Modern Languages, James’ sense of poetic form is playful in its use of French phrases, literary quotations and punctuation marks; it is acutely aware of its own sounds and intonations. Her verse elaborates on anything from holding hands to watching TV.

Sarah James’ Plenty-fish cannot be gulped in one go, slipping as it does magnificently around in the imagination, never quite solidly poetry, but fleshy and fresh. The seventy-one-piece collection contains poems of varying lengths – all semi-anecdotal and detailed accounts of everyday life. As a graduate in Modern Languages, James’ sense of poetic form is playful in its use of French phrases, literary quotations and punctuation marks; it is acutely aware of its own sounds and intonations. Her verse elaborates on anything from holding hands to watching TV.

Throughout the collection there is a palpable sense of the intimate. James invites her readers to glimpse moments of closeness – not in a confessional, dramatic way, but subtly. Take, for instance, “This Holy Shrine”:

the clink of my bracelet’s love heart on glass

breaks our glazed dumbness. I miss the boys,

he says. And there it is, our flesh union.

He rests one hand on mine. Its thin gold glints.

Concise lines hint at a shared intimacy without any need for flowery language. The personal is made sensual; we are made to hear the “clink” of her bracelet and see his ring’s “glint” . This is one of the warmer poems here, but there are some equally close but despairing snapshots of James’ life. James draws from times of heartbreak, loss of faith, loneliness and the bittersweet in captured images that explore wider themes of life, love and death, uncovering her experiences as a work of nature in the ecosystem of what it means to live today.

Many of the poems in the collection voice a woman’s perspective with clarity and honesty. James writes with a vulnerability similar to the one we hear in Carol Ann Duffy, unafraid to showcase truths of motherhood and therapy experienced, exploring what it’s like to perform the tasks her therapist sets or the amusement her youngest son gives. Raw loneliness is rendered beautifully;. in “Cactus Ballgown”, she prepares not only to go out but readies herself to return home partner-less, comparing her dress to a cactus:

Above all, beware of the needles when you un-

dress alone, your skin riddled now with pins.

It is both endearing and interesting to read James’ pic‘n’mix of scientific references littered throughout the collection; asterisks mark accompanying factoids that imbue poems with further meaning referring, for example, to light frequencies and biology:

Stem cells multiply, colonise, grow (“Transplanted”)

James responds to specific articles from The Guardian on the state of the environment. Arguably, the collection is split between the profoundly personal and the resolutely external, demonstrating a keen interest in the natural world and encouraging her reader to engage fully with it. Sometimes, however, this can distract from the verse. This very imbalance is, perhaps, subliminally rectified in other poems entirely devoted to a single theme. In “Wired flesh” she makes observations technology’s on hold in contemporary culture:

Computer in his lap, graphics trigger laughter,

Frowns, sharp exclamations in code.

Aged eight, already part-strange to me.

Yet, rather than lapse into cynicism, James is able to couple the ever-changing world of technology with the unchanging nature of parenthood: the quiet surprises and confusions of the younger generation.

A certain Pink Floyd song comes to mind after reading the collection, “We’re just two lost souls swimming in a fish bowl, year after year”. We all live in inextricable bubble, a place of nature and loss to wander through; language is James’s way out… and perhaps it might be ours too.

Zoe Cassells

[…] …Many of the poems in the collection voice a woman’s perspective with clarity and honesty. James writes with a vulnerability similar to the one we hear in Carol Ann Duffy…” Zoe Cassells, DURA (Dundee University Review of the Arts). Full review here. […]