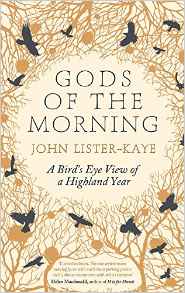

Gods of The Morning: A Bird’s Eye View of a Highland Year

John Lister-Kaye’s ninth book, Gods of the Morning: A Bird’s Eye View of the Highland Year, reflects on landscape and wildlife, particularly birds – Virgil’s “gods of the morning” – over four seasons at Aigas, the Highland field centre by the Beauly River, which he owns.

John Lister-Kaye’s ninth book, Gods of the Morning: A Bird’s Eye View of the Highland Year, reflects on landscape and wildlife, particularly birds – Virgil’s “gods of the morning” – over four seasons at Aigas, the Highland field centre by the Beauly River, which he owns.

The book opens with the death of a blackcap which flies unawares into Lister-Kaye’s study window: “That little warbler had fired something in my brain and caused me to write this down, and that departure, as the season wafted silently away from summer, was where I needed to start. Perhaps, after all, its death was not in vain.”

Lister-Kaye’s writing is not the most lyrical of nature-writing – often when he cites other writers, his own words pale by comparison. Nor does he write for the bird aficionado – most of his ornithological observations will be familiar to avid birders. And his environmental reflections are ambivalent – he is doing as best he can, in his own mind, to safeguard his bit of the Highlands, yet doubts creep in about the extent to which humankind can prevent climate change. It’s hardly a book for diehard environmentalists. But as one man’s consideration of aspects of a Highland Year, it is thoughtful, honest and interestingly nuanced.

Lister-Kaye is at his best when describing the landscape and wildlife with which he is so familiar. As he says, Google only skims the surface of information. He brings the insights of a lifelong, patient observer in close relationship with his surroundings. At one point, on a precipice in a white-out, he comes face to beak with a raven – “I was in a place where she had never seen a human before; she was closer to a man than she had ever been, without knowing or understanding how I had got there. I was lying down; I was silent and motionless and, like her, I was snow-dappled from woolly hat to gaitered boots […..] Very slowly her head lowered once more until her great black bill was resting on the rim of the nest. Her eye closed, the pale lower lid lifting uncertainly until the pearl was gone.”

The stories of his childhood and the rescued birds and animals held in captivity, such as Squawkie who touchingly recognised him many years later, and the second-hand information about geology, I found less compelling. Similarly, I was irritated by his slightly boys’ own take on Orcadian prehistory in which he imagines the incumbent of the Maeshowe chambered cairn was “no doubt a thoroughly good bloke. He’d probably sired fine sons, won battles, lopped off a few truculent heads […]”.

Similarly, his attitude to his wife, Lucy, becomes a little wearing: “Lucy has lit the sitting room fire…. I shall repair to my old armchair with a book.” When wood mice move indoors, “unlike Lucy when she’s in hyper-efficient housekeeper mode, I am overcome by a downward somersault of the spirit when called upon to trap them.”

Lister-Kaye’s tendency to anthropomorphise says rather more about him than the birds and animals he describes: to him, rooks are “like inner-city youths”, and red squirrels are furtive, like “shoplifters”.

At times, he is nostalgic (for fox hunting and for game shooting that is “recreational” and “social” rather than “economic” ); elsewhere he is relieved that change has come about (no more strychnine poisoning of ravens by gamekeepers, for example).

I often found aspects of this book irritating yet I have to admit there is something engaging about how Lister-Kaye sets out his stall, warts and all.

Lindsay Macgregor

Leave a Reply