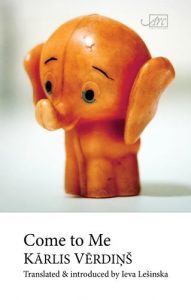

Come to Me

“Ergo bibamus, my prince, we stole an entire country like one empty heart.”

“Ergo bibamus, my prince, we stole an entire country like one empty heart.”

Latvian poet, Kārlis Vērdiņš (born in 1979) has already been anthologised in Arc’s Six Latvian Poets (2011, also translated by Ieva Lešinska) but with four full poetry collections, a career encompassing criticism, translation, song lyrics, libretti and more, he is both versatile and distinguished. Indeed, Vērdiņš has translated Eliot, Brodsky and Whitman among others – perhaps an interesting, unanswered question arising from this fine Arc Translations title is why he chose not to translate his own poems. However, in Lešinska, Vērdiņš has a very admirable translator who has also translated not only Eliot, but Hughes, Heaney and other giants.

Lešinska’s fulsome introduction describes the poet as part of “the generation of Latvian poets who came into their own in the mid to late 1990s when the political turmoil had subsided and a period of relative calm had set in.” She quickly identifies Vērdiņš’ central themes, clarifying his position as a pre-eminent voice in an emergent nation , moving in “new European and pan-Atlantic socio-cultural structures”. Soon, we understand the poet’s need (and indeed his nation’s literary need) to break taboos, cut through “silence and ignorance concerning gays, gender issues, and alternative lifestyles in this rapidly opening society.” “The inescapable same-sex eroticism” of his first book was “so universally sensuous and emotionally pure that it seemed not to offend the most homophobic readers” and “agressive social provocation is hardly Vērdiņš’ style”. His translator is unsure if Latvians are admirably tolerant, or if poetry readers deserve that credit. Either way, she is right. This collection doesn’t preach.

These intense, varied poems have a strong underlying, apparently autobiographical, narrative. Whilst they explore both relationships’ triumphs and traumas, their essence is quirky rather than angst-layered, characterised by strong, delightfully surrealist thinking. Vērdiņš’ prose poety is powerful, and his essay elsewhere on the particularly Latvian form suggests that there is a great deal here as yet inaccessible to most non-Latvian readers. Nonetheless, even for the non-specialist, these are engaging, mostly joyous poems. Prose in likeness certainly, but poems undoubtedly, highly disciplined in their shape and whitespace use; for this reviewer, it is in this form, rather than the perhaps more familiar stanzaic examples where the poet truly revels.

We discuss strange suicides, particularly funny funeral

customs. Now and then, someone pretends to be

dead, others tell beautiful stories and say how much

he’ll be missed.

In this dry cellar where pickles gleam in glass jars, where

strings of onions sway in the breeze and where

orange pumpkins grin toothlessly on shelves.

This poet is playful not only with life, but death.

Even the English-speaking reader will likely attempt some comparisons in these parallel translations. Without the language, it is impossible to tell if the translator’s sometimes archaic vocabulary (“Let clenched fists and head hidden under a blanket speak”) and structures are faithful or not. Sometimes, the folkloric aspects suggest so, but sometimes this is less sure. Certainly the English is rather more straightforward than the fluid Latvian original. The English is US, rather than UK, but sometimes that translation, rich in internal rhyme or strongly alliterative, as in the indented quotation above, does not reflect the original patterning. Elsewhere, it is perhaps unsurprising to see the word “shit” used strongly and repeatedly in one poem, including as “bullshit” which does not appear as a translated calque. Different languages undoubtedly handle scatalogical matters differently! What does surprise is when that same English word appears differently in the Latvian when it occurs elsewhere, especially when the word occupies the poem’s dynamic last breath. As Latvian has a smaller lexicon than English, this seems odd. All this asks questions of poetry in translation… and yet I offer great respect to Arc for this wonderful, thought-provoking series.

We are indebted to Arc for this rich introduction to a major European poetic voice who is likely to be new to most U.K. readers. Who could fail to enjoy his vivacity?

Beth McDonough

(with thanks to Julija Danilova for advice on the Latvian translation)

Leave a Reply