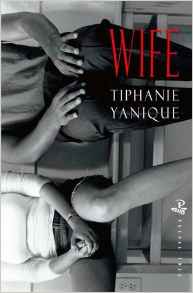

Wife (Winner of the Forward Prizes for Poetry 2016: “Best Debut Collection” )

True, we will never be

beyond our histories.

And so I am the island.

And so this is a warning.

Wife opens with “Dangerous Things” ; a few pages later, the full-page prose poem “Dictionary” sets out a clear stall as to how that titular word might be explored, initially from a European perspective, then

Wifey – (American Negro origins) diminutive of wife, but more desirable. Girl who cooks, cleans, fucks and gives back massages,

through “get wife”, a verb of Caribbean connections, to the unknown source of “to wife […] a feminine specific”.

However, any reader lulled into believing these two poems offer the key to this short but highly demanding collection will be surprised.

Wife is Virgin Islander Tiphanie Yanique’s first full poetry collection for adults. She is already a well-lauded fiction writer and has collaborated with her husband, photographer Moses Djeli, in an earlier children’s collection. In her closing acknowledgments here, Yanique offers a wry, touching tribute to his constancy “despite the betrayal of my being a poet”. Indeed these poems ask much of him.

That “unknown source” of “Dictionary”’s fourth definition is telling. Yanique is a recognised, perceptive voice on Pan-African culture, and Christian Campbell has described how Yanique “ventriloquises a range of historical and imaginary female figures and ventriloquises herself.” In so doing, she explores her own situation, both in a deeply personal way and in its wider, cultural context, the experience of women from an array of times and places. As poet Yanique also achieves something rather more subtle. By these shifting, disguising literary and thematic devices, she refuses to allow her reader to own the object of her focus. Whenever a reader might feel a closing in, a getting it, something slips under the door. Wife refuses to be defined or summed up easily… or perhaps at all. Thus Yanique’s reader had better stay alert. Sometimes in the first person plural and elsewhere in an interrogative second person voice, this poet will not allow an unengaged reading.

In that first section (of four), “Zuihitsu for the day I cheat on my husband, to my fiancé” is the only poem claiming to be of that 10th Century Japanese form. However that “following the brush” stream of consciousness-type of autobiographical poem, fragmented and almost ecstatic in its delivery, surely underpins a great deal here.

Often there is an incantatory quality to her repeated short lines, which are sometimes of surprisingly workaday vocabulary. These are poems I would especially appreciate hearing her perform; recognising my own Scottish accent and different delivery short-changes her words when I read them aloud. That particular musicality in her work is beautifully formalised in an epithalamion, using the traditional Virgin Islands’ form.

Yanique’s Wife may be found in contemporary New York, sighted in shape poems, in Greek mythology, the Bible, in birth and maternity, squaring up to a mother-in-law and in the search for Jean-Michael Basquiat; arguably Yanique is never more powerful than in “Chief Priestess Say”, a complex response to the Fela Kuti’s music, with its continuing repercussions in African feminist thought. Despite the poem’s titular outward clarity, “Chief Priest Say” is not the only song echoed here, as a close reading shows an underlying response to his highly-problematic “Lady” and more. Here that African Aje (usually “witch”) voice seems strong:

Most men are zombies. In spirit,

it is always the women who carry

the coffin.

In truth, this white Scotswoman reviewing has doubts about prize hierarchies, and cannot say how this collection will be received. Moreover, I am painfully aware that I am ill-equipped to read Wife in the fullness of its cultural undercurrents, and it is absolutely right that this reading should challenge me. Some of the most extraordinary – and my most loved – voices in contemporary poetry are sounding from the Caribbean. How doubly wonderful to see Tiphanie Yanique and the very excellent Peepal Tree here.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply