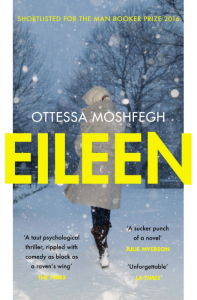

Eileen (Shortlisted for the 2016 Man Booker Prize)

Ottessa Moshfegh

(Jonathan Cape, 2016); hbk: £14.99

Ottessa Moshfegh has won the Plimpton and Fence Modern Prizes for her shorter fiction, and her debut novel Eileen is now lined up for the Booker. One might ask what allows this author to dive in at the deep end of critical acclaim. If Eileen is anything to go by, it is either the ability to shock, to write characters, or to be able to convey the atmosphere of X-ville, the no-name town somewhere on the East Coast of the USA. This is all very fitting for an anti-heroine who delights in all things scatological. Or rather, “used to”, as the story is presented retrospectively, fifty years after the events in the book occur.

Ottessa Moshfegh has won the Plimpton and Fence Modern Prizes for her shorter fiction, and her debut novel Eileen is now lined up for the Booker. One might ask what allows this author to dive in at the deep end of critical acclaim. If Eileen is anything to go by, it is either the ability to shock, to write characters, or to be able to convey the atmosphere of X-ville, the no-name town somewhere on the East Coast of the USA. This is all very fitting for an anti-heroine who delights in all things scatological. Or rather, “used to”, as the story is presented retrospectively, fifty years after the events in the book occur.

Now, of course, there is no more delight to be had in all of the crazy things “old Eileen” did. Or is there? The advantage of having this highly unreliable narrator is that we are unable to tell whether seventy-four year old Eileen is mocking herself, the reader, or both. Throughout the novel, this ambiguity remains a problem, because it is unclear how seriously we should take it. None of the tropes are particularly innovative; the way Eileen revels in her filth has been done before, notably by Rabelais. The only twist on Rabelaisian scatology is that we are repeatedly told how much Eileen menstruates, which adds a female perspective to the genre but otherwise does not shock much. Even the “beginning of the dark bond which now paves the way for the rest of my story” falls incredibly flat, for two reasons. For one, the climax of the story is foreshadowed constantly. For two, everything, including the foreshadowing, is explained to death (pun intended). Neither of these points is helped by the inclusion of the deus-ex machina appearance of Rebecca, without whom there would be no plot worth mentioning.

Arguably, this is the point. Interestingly, Moshfegh’s repetition of facts, such as: “I was easily roused by the grosser habits of the human body – toilet business not least of all.” By the time we get to this sentence, the repetition of grotesque behaviour and habits has become white noise. And yet, there is practically no repetition of diction. In other words, we are given a study of all things repugnant from as many angles as possible. Still, the question remains how relevant all this is. In Eileen’s words: “I preferred to wallow in the problem”. Whether we consider her mentally ill (she does have symptoms of anorexia nervosa), or whether we think she should just get a grip becomes as irrelevant as Eileen thinks her story is: “nothing special happened that night. It’s just a place to begin.”

Readers who are looking for a (well-crafted) plot will be sadly disappointed, but plot is not the reason why this book was written. Indeed, it might have benefited from not having a plot at all. Some aspects, which are mainly related to the climax, seem somewhat pointless in Eileen’s character study. Eileen’s workplace provides the background for a secondary narrative, which is wedged into the character study for no adequately explored reason. Perhaps it is there to shock, perhaps it is there to be sociologically relevant, or perhaps it is there as a reminder that 60’s America was obsessed with psychiatry. Whatever the reason, the result is that the supposed high of the story feels forced.

This is not to say that Eileen is poorly written. In fact, the contrary is true because it is quite technical yet easy to read. Is the novel perhaps trying to be too clever for its own good? Or is it simplistic, with social and psychological elements thrown in to seem relevant? Or is it indeed the masterpiece it is made out to be? Whatever it is, it is certainly entertaining enough, assuming that you are not squeamish.

Jérôme Cooper

Leave a Reply