The Idea of North

In Brussels in 1511, figures are sculpted from the snow that has fallen for weeks. They include commissions sculpted by artists and the subjects Charon, Pluto and assorted Devils. Winter has brought the beauty recorded in Breughel’s playful paintings to the southern Netherlands. It also destroys. It kills. This dichotomy is central to Peter Davidson’s reissued book, The Idea of the North.

In Brussels in 1511, figures are sculpted from the snow that has fallen for weeks. They include commissions sculpted by artists and the subjects Charon, Pluto and assorted Devils. Winter has brought the beauty recorded in Breughel’s playful paintings to the southern Netherlands. It also destroys. It kills. This dichotomy is central to Peter Davidson’s reissued book, The Idea of the North.

He begins with a description of a compass made by the Scottish artists Dalziel and Scullion. Inscribed with the words, “The Idea of the North”, “wherever the compass “is located, it points to a further north, to an elsewhere.” This sense of movement, not only from place to place but also from one idea to another, suffuses the text.

The Idea of the North is dense with references to ancient literature, to mythology. Davidson’s academic background is on display. His knowledge and his erudition are astounding. There are contemporary references too, Finnish glass made to resemble ice, the use of snow as a medium to practise new ideas in architecture. Even contemporary crime fiction becomes a source; the final, apocalyptic scene in “Miss Smilla’s feeling for Snow” by the Danish writer Peter Hoeg, is based on Inuit myth. Opposites are explored, the North as a fount of treasure, amber, narwhal horn and sable and as a monster filled, violent and tempestuous landscape that flickers with flame.

Some references are dispatched quickly. W.H. Auden’s poetry and the artist Eric Raviolis” empty, glittering landscapes are considered in more detail. Davidson contrasts them with the artists of 1920’s who looked south for a more indolent, sun filled inspiration.

Every sentence in this book is poised and lucid. Davidson uses repeating refrains to help the reader link the different sections. They include quotes from the contemporary poetry of Pauline Stainer and constant references to the “Hyperborean”, that paradisiacal world of Greek mythology that is to be found beyond the North.

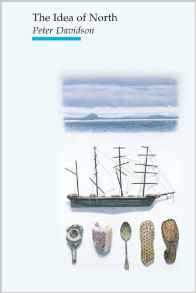

There is material here, enough starting points, for several books. I am left with a series of fantastic visual images, the shattered lake in the centre of the Snow Queen’s palace, Reinhardt Behrens’ created world of “Naboland”, laid out on the book’s cover as an illustration of surreal archaeological finds, the burial mounds of the Icelandic dead, close to their farms, “their inhabitants spoken of as present, drowsing rather than dead”. I am left with reading to pursue, places to visit and prompts for writing.

I think about the “norths” I’ve experienced, the child’s journey from South Wales to the mountainous North that seemed like an impossibly long adventure, always about to be thwarted by an elderly, underpowered car, that trip to the fringe of the Arctic circle where vintage American cars circled a blood red Timber church in the midnight twilight of the Arctic summer, our journey from the South west of England to Scotland, our new home surrounded by the remains of the stone settlements of other, earlier travellers, discovering their own north.

The last chapter of the book describes a northern winter, the dangerous uplands where conditions are liable to change at any moment, filled with the noise from the migrating geese overhead. Consolation is sought in smoky food, in whisky. This feeling is accessible to any Northerner. Another winter survived is another year passed. He concludes by saying “Almost everything that consoles us is false.” Winter will return. We’ll be older. It will get harder.

In the epilogue, Davidson retreats to his study and views the weather of the northernmost parts of Scotland on webcams, describing what he sees with the words of a poet, maintaining that precise, elegant, elegiac tone, “a block of dusk above a block of moor. A smear of dark above a line of snow”.

Sarah Isaac

Leave a Reply