maritime

It’s sad when a word is poisoned by history. The word I’m thinking of is “collaboration.” Is it possible to wash off the wartime smear of sleaze and shame that this perfectly good word has acquired? What it describes really is something to be proud of, requiring both a clear personal voice and a generosity of spirit. Of course there is an inherent tension in any collaboration; it must be built from the differences between the partners and achieved through a balancing of otherness in a common cause.

It’s sad when a word is poisoned by history. The word I’m thinking of is “collaboration.” Is it possible to wash off the wartime smear of sleaze and shame that this perfectly good word has acquired? What it describes really is something to be proud of, requiring both a clear personal voice and a generosity of spirit. Of course there is an inherent tension in any collaboration; it must be built from the differences between the partners and achieved through a balancing of otherness in a common cause.

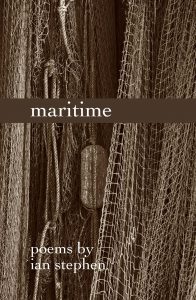

I want to have use of the word for Ian Stephen’s work, and in particular his recent poetry collection maritime. In the past he has collaborated with musicians, composers and translators, and taken part in group projects in Brittany, Canada, the Mediterranean and Tasmania. For maritime, he has collaborated with photographer Christine Morrison, who provided the cover image and chapter headings throughout.

An air of collaboration also inheres in the poems themselves – a collaboration between poet and place. The collection is set in and around Lewis and the Western Isles, where Stephen has lived and worked most of his life. In a way, those who live off the sea and by the sea can’t not collaborate. Conquest is not an option, though death is. And that necessity produces an acceptance, a “calm” amidst the relentless sibilance of the sea, which Stephen identifies in, for example, the poem “Shiant shepherds”:

These five ordinary souls

worked out their weeks on the Shiants

on turf-padded rocks, mid-Minches

while their climber ewes had their lambs.They wear their eccentricities

in their tammies and bonnets but

these men with the calm in their bellies

lived somewhere obscured to ourselves.

Stephen’s poems have a stillness to them, even when they are dealing with the wild wave-tossed sea. They move between a long-sightedness and a precise focus. I loved the closely observed details:

Colour diminishes

to the white of one egret

the grey of eight herons.

(“Exemouth”)Your salt-clogged hair

is rippled like

long abrasions

in sea sand.

(“At Luskentyre”)

Some of the poems come directly from Stephen’s time working for the Coastguard on Lewis. Understated, almost laconic, snippets of experience and memory:

This time the seas go back.

Shed tails of kelp are left

on the tarmac of the isthmus.

(“Night watch”)The sea released them

a fortnight later

when pressure relented.

(“Fatal Accident Inquiry”)We sent a chopper with potent spans

of live lights. It only found

a brash litany

of flotation devices.

(“I’ll boil the kettle”)

I was particularly drawn to the Gensey sequence, having only recently learned that each fisherman’s sweater was traditionally knitted to include a few unique mistakes, so that if its wearer is drowned and cast ashore, the body may be identified no matter what damage it had sustained.

I’m wearing your patterns.

Your threads are holding

my tired bones.

You’ll have me home yet

Marybell of Bayhead.

(“Bella’s man”)

In “Boat-burning”, Stephen writes “I strain to see more than what’s visible …” His poetic practice makes use of free verse, short lines, spare vocabulary – all perfectly suited to the task. He is not a poet who dances and shouts, “Reader! Look at me!” He is a poet who says, with beautifully realised precision and loving control of the words, “Reader, look with me.”

Part of every reading experience is the medium, and in this case, that medium – a final collaboration – is a pleasure. Light and smooth in the hand, with a cover image that draws the eye, a generosity of inside folds, and typesetting and design by poet and font aficionado Gerry Cambridge, maritime issues an invitation which I would warmly recommend you accept.

Joan Lennon

Leave a Reply