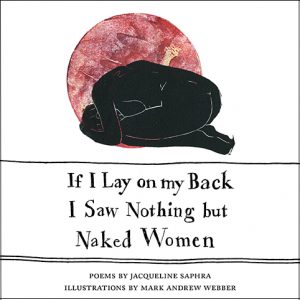

If I Lay on my Back I Saw Nothing but Naked Women

Jacqueline Saphra’s If I Lay on my Back I Saw Nothing but Naked Women is a collection of eighteen entertaining prose poems that weave together several stories recounted from the narrator’s childhood. Saphra’s absorbing and entertaining words paired with Mark Andrew Webber’s captivating illustrations make for an enchanting small book, plunging readers into a world of vision and imagination. Easy to digest, Saphra’s childhood tales are rendered as thoughtful and heartfelt poems are matched by Webber’s vivacious illustrations.

Jacqueline Saphra’s If I Lay on my Back I Saw Nothing but Naked Women is a collection of eighteen entertaining prose poems that weave together several stories recounted from the narrator’s childhood. Saphra’s absorbing and entertaining words paired with Mark Andrew Webber’s captivating illustrations make for an enchanting small book, plunging readers into a world of vision and imagination. Easy to digest, Saphra’s childhood tales are rendered as thoughtful and heartfelt poems are matched by Webber’s vivacious illustrations.

Saphra started writing poetry at the age of five. On her official website she writes: “on a chequered journey I moved on to songwriting, playwriting, screenwriting and stand-up comedy before I rediscovered poetry, my first love.” A poet and an editor, and also a teacher at The Poetry School and Word for Word, Saphra’s love of poetry is demonstrated in her marked obsession with words, a topic that is addressed in the collection repeatedly. The narrator’s child-self states: “I hide problematic words in case I need them later. Sometimes they whisper in the dark. At quiet moments, if I put my ear to the ink blotter, I hear the longer ones mount the shorter ones.” Clearly, words are a fundamental and animated feature in her writing life. In If I Lay On My Back I saw Nothing but Naked Women, the creative potential of words, and especially poetry, can offer solace for a disjointed and dysfunctional childhood.

Both the opening and closing poems begin with “When I was a child”, signalling that we are dealing with situations through very young eyes. Innocent, honest and naïve, these poems detail the encounters of the narrator’s idiosyncratic and outlandish parents and step-parents:“I sat quietly on an ink blotter while my mother plaited my hair and father listened to my heart.”Whilst the poems are approached through the filtered and innocent perception of a child, they deal with serious issues such as divorce, the need for a father’s influence and the incessant introductions and departures of step-parents. The negativity associated with a lack of fixed and consistent early guidance is examined closely in Saphra’s final poem where she describes what it is like to live with divorced parents. Torn between two worlds and two sets of authority, the narrator points out: “When I was a child my mother and father lived on different continents. I flew between them. […] Certain phrases were often bent or broken in transit, complete sentences drifted away and were lost in the exchange.”

The story of a young girl’s perceptions of her alienation within her family and ultimately, her life, is beautifully captured within the final lines of this small book: ‘the words waited immutably in the dark.’ Saphra may be dealing with the eccentric behaviours of a child’s parents and step-parents through a comical lens but each poem has an undertone that hearkens to matters both sombre and meaningful. Consider the smashing of her mother’s new-fired pots because they did not turn out perfectly; even pouring water became a “daily trial of nerve”. Meanwhile her father’s third and final wife “bagged up all my old words, took them to the charity shop in her rusty Honda and redesigned my father’s house around him.”

Captivating, vivid and amusing, Saphra’s poems hint time and time again at the comical and serious upheaval in a young girl’s childhood as she is forced to deal with very adult and unreasonable issues. Webber’s abstract illustrations of naked women underscore these poignant undertones. Humorous, playful and pathos-laden, this wonderful collection will simultaneously mesmerize, enthral and enchant its reader.

Sioned Raybould.

Leave a Reply