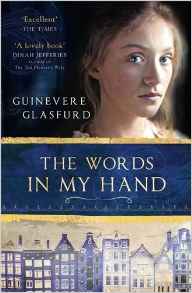

The Words in My Hand (Shortlisted, 2016 Costa First Novel Award)

Stories have the power to entrance and captivate, giving them the ability to teach, comfort and even inspire the reader or listener. In The Words in My Hand, Guinevere Glasfurd explores the impact of words and writing in the life of Helena Jans, René Descartes’s maid and also mother to his illegitimate child. Helena was literate despite her sex and social standing. The power of stories as a liberating force is a strong theme. Helena is restricted as a maid and as a woman but she is able to teach herself to write and in doing so gains freedom in words. At its heart, this is a book about writing: Descartes writes novels while Helena hides her paper and quills, using them in secret and thus making them all the more sacred.

Stories have the power to entrance and captivate, giving them the ability to teach, comfort and even inspire the reader or listener. In The Words in My Hand, Guinevere Glasfurd explores the impact of words and writing in the life of Helena Jans, René Descartes’s maid and also mother to his illegitimate child. Helena was literate despite her sex and social standing. The power of stories as a liberating force is a strong theme. Helena is restricted as a maid and as a woman but she is able to teach herself to write and in doing so gains freedom in words. At its heart, this is a book about writing: Descartes writes novels while Helena hides her paper and quills, using them in secret and thus making them all the more sacred.

The book is separated into seven sections, each section an insight into Helena’s life in a different year. However, it does not start from the beginning of Helena’s story; instead Glasfurd throws us immediately into the action of a highly emotionally charged scene, where a tearful Helena is being sent away, before taking us back a few years for context. Glasfurd certainly captures our attention. We have no other choice but to read on to discover what is happening to Helena in the opening chapter. While this revelation is a slow-burn, Glasfurd uses her affinity for creating tension to keep the reader invested in the characters from start to finish.

As an unmarried mother and servant, Helena all but disappears from history. One of the first things to notice about the book is it’s easy to read, using flowing modern English. By writing naturally rather than trying to recreate the language of 1634, Glasfurd creates a story that enables all readers to effortlessly slip into a world they never imagined visiting: “The reading of all good books is like a conversation with the finest minds of past centuries.”

This quote by Descartes is particularly poignant. 400 years after his death he is given a principal role in Glasfurd’s novel but from Helena’s perspective. Writing the novel from the point of view of Helena’s life, Glasfurd is able to cast Descartes in a different light from that of the loner philosopher. We are instead gifted with a complex man with complicated relationships and emotions. Glasfurd imagines and creates a dynamic between them and expands creatively on the historical information about them already in existence.

In real life, Descartes was unable to admit to being father to Francine, and so a pseudonym of his name was used on the baptismal certificate. Glasfurd uses this historical anecdote and backfills it with layers of emotion, providing insight into what convincingly could have been Helena’s feelings in having to hide the father’s identity. Moments like this based on real stories give great depth to the novel, and demonstrate Glasfurd’s flair for conveying human emotion, no matter how intricate.

Clearly, this novel offers a celebration of stories, depicting Descartes frequently inventing snippets of his next book, and Helena writing in secret and teaching her daughter the same skills of reading and writing. In this novel, stories are comforting and an escape from the harsh reality of the world story-telling is used to soothe a sick Francine and, frequently, to ease Helena’s mind. This story of literacy should ultimately inspire the reader to pick up a pen and begin to write their own tale.

Dervla McCormick

Leave a Reply