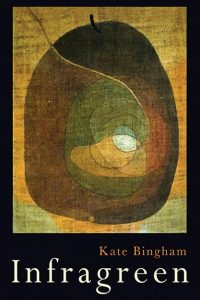

Infragreen

The taut neologism of the title, under Paul Klee’s glorious painting “The Fruit, 1932”, in tandem with the titular poem and the opening of “Ultragreen”, convinced me I was about to read a collection devoted to the study of synathesia. I was very wrong, despite that first section’s immersion in colour which fades slowly into the second’s quite different concerns.

The taut neologism of the title, under Paul Klee’s glorious painting “The Fruit, 1932”, in tandem with the titular poem and the opening of “Ultragreen”, convinced me I was about to read a collection devoted to the study of synathesia. I was very wrong, despite that first section’s immersion in colour which fades slowly into the second’s quite different concerns.

It turns its eye in my brain, looks out

and sees what I have seen.

Something like photosynthesis begins.

Having read history at Oxford, and then opted out of the offered “safety” of a career at the Bar, Kate Bingham has written scripts and volunteered in El Salvador; she is also an accomplished illustrator of airy, linear work. Infragreen is her third full poetry collection. Her concerns are not simply with colour, but with the observation of life in all its forms – hers is indeed a vigilant eye.

Carol Ann Duffy commented “I’m not interested, as a poet, in words like “plash” — Seamus Heaney words, interesting words. I like to use simple words, but in a complicated way”. Certainly that was no callow dismissal of the elder poet’s lexicon, but self-awareness. Despite Bingham’s “Infragreen” and “Ultragreen”, something similar might be said here, as the poet observes the quotidian using, for the most part, a commonplace vocabulary. Infragreen is an investigation, “[n]eccessarily […] the familiar, the seen again, the returned to.”

In three parts, the poet seeks patterns in her careful observation of the domestic, the natural, the seasonal and more. All of this rendered through poetic form’s exacting filter. The jacket explains “those very things that normally lull the brain into unthinking acquiescence are necessarily observed for signs of change.” Some of her most successful poems are subtle but sharp; here she watches insidious changes in a long-term relationship:

how many nights had I ignored

your tics and twitches, sighs and sweats[.]

Neither is Bingham slow to find humour in poems like “Between Our Feet”, with its almost adult nursery rhyme-styled take on aging. Elsewhere there are references to Burns, Hardy, Frost, and nudges towards Heaney and Hughes (most particularly in those thistles, seeding through the collection). William Henry Davies’ most famous need to “stop and stare” resonates throughout, but it is Bingham’s love of form which predominates.

The second section in Infragreen is particularly rich in sonnets, including two ambitious triptychs (“The Wood” and “Tapetum Lucidum”), but there are many more forms than that present. Ballads, a cento stitched from lines from Christmas carols, some almost-villanelles (depending on line endings rather than full lines for their patterning) and other rhyme-heavy nonce forms. The poet is strict indeed with these, and asks a great deal of her words. How many would like to write a sonnet using the word “string” for half of the line endings? Would we be prepared to throw some fairly full-on rhyme into that mix, allowing only the rather splendid volta of “Cadbury’s Eclair” to stand free of those constraints? In isolation, this would be chutzpah indeed, as would the brilliantly deft mirroring in “Arrangements” and Bingham’s deliberately mind-numbing poem to a packet of contraceptive pills … but for this reader, the cumulative effect was problematic.

I greatly admire how well-used form can harness emotions which might otherwise scattergun. However, there is something seductive about being slipped into a truly effective sestina, finding yourself half way through before you notice the form. All too soon, I felt the forms were offering their calling cards ahead of the poem itself, especially in their use of overly familiar and repeated words. Sometimes I sensed that the lines strained in their cleverness to comply, and I found myself looking for patterns before the poem. I am aware that the poet crafted these lovingly and well, and that for some that obsessive premature unravelling will be a joy rather than a hindrance. That is, of course, for the individual reader to discover and decide.

Beth McDonough

Leave a Reply