On Poetry and Writing: An Interview with Don Paterson

“So Don, why do you love poetry?”

“So Don, why do you love poetry?”

It takes only three words of Don Paterson’s reply to what I naively think will be a nice, easy first question for me to understand that this is not going to be an hour of nice, easy assumptions.

“Oh I don’t” he replies immediately “that would be a mistake. I think just because you do something needn’t imply love.”

Oh. My heart doesn’t exactly sink, but I am left with the feeling that I had better wise-up.

I shouldn’t really be surprised. Not much that is good about poetry is easily defined and Paterson’s best work has the habit of confounding expectations. His most recent collection, 40 Sonnets, moves effortlessly across subjects and styles, with intensely personal poems about his children sitting comfortably side by side with a political poem about Tony Blair, or a poem that manages to find the profound in Hugh Lawrie’s T.V. doctor House.

The trouble is, it is easy to approach an interview with a ‘great poet’ with a little too much wide-eyed reverence. Don Paterson has achieved a lot, winning the Forward prize, the Whitbread prize, the T.S. Eliot prize, the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Award, the Queen’s Gold Medal for poetry and an OBE. His most recent collection 40 Sonnets won the 2015 Costa poetry award. The blurbs on his collections wear the words “finest”, “foremost”, “stunning” and “genius” with alarming ease. He teaches poetic opposition at the University of St Andrews and on his door hangs the word Professor. Here I am, having had the chutzpah to ask for an interview, the bumbling student with the great poet serving me tea.

I have another confession. I do love his writing. At the end of the interview Paterson laughs when I tell him about discovering his aphorisms in a collection of new British writing, published in the early 2000s. He jokes “The aphorisms? I thought the poems were badly paid, but the aphorisms are truly pointless…” But of course they aren’t. Aphorisms wear their point on their sleeve; they are little snippets of pleasing wisdom. It is the search for a little bit of this wisdom that has me in his office. The thing is though, while the playing things down is unnerving at first, it is this humour and undermining of expectations that so often makes his work interesting and approachable. The poem ‘House’ deals despairingly with illness and death and yet is punctuated with “Stop the Chemo! He just needs to fart!” Yogic reflection and “silent retreat” can be compared to “the latter stages of a gin hangover”. There is something about this approach that feels, for want of a better word, wise.

Paterson seems far more comfortable referring to the poems in 40  Sonnets he feels are “duffers”, not descriptions I agree with. He takes perverse pleasure in his brother sending him the tweets of school pupils made to study his poetry for Higher English: “Don Paterson’s a baldy bastard… Don Paterson’s poems are shite.” Compared to some other Scottish poets, Paterson is refreshingly relaxed, both with being a ‘set-text’ for the SQA, and with what he sees as the mostly enthusiastic teaching of poetry in schools. Still, he can’t resist reflecting on the tweets: “This is what you get for being ambitious? Nice one Don!”

Sonnets he feels are “duffers”, not descriptions I agree with. He takes perverse pleasure in his brother sending him the tweets of school pupils made to study his poetry for Higher English: “Don Paterson’s a baldy bastard… Don Paterson’s poems are shite.” Compared to some other Scottish poets, Paterson is refreshingly relaxed, both with being a ‘set-text’ for the SQA, and with what he sees as the mostly enthusiastic teaching of poetry in schools. Still, he can’t resist reflecting on the tweets: “This is what you get for being ambitious? Nice one Don!”

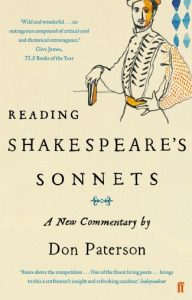

If the self-deprecation felt like an act, then it might be wearing. But while I have to restrain a slight urge to shake him and say ‘Man, go easy on yourself!’, it is as refreshing to hear him talk in this way as it is to hear him refer to Shakespeare’s “rubbish” sonnets. His book Reading Shakespeare’s Sonnets is a kind of reading diary where one or two poems are read and reflected on every day “wide awake, bored, half-asleep, drunk or hungover… on the train, in the bath and in my lunch break”. It is all about looking at ‘great’ poetry again to see what we can still get out of it day to day. Such poems may only be ‘rubbish’ in comparison to other poems, but you miss the point if you don’t engage with them on a personal level.

Anyway, going easy on himself would be an anathema to Paterson: “I don’t want to read anything that hasn’t half killed somebody, so the least I can do is expect the same of myself.” Taking poetry off its pedestal clearly does not mean that it should come easy. For any budding poets out there, the way Paterson describes the process of writing could be off-putting. He says he doesn’t write for pleasure any more. He says that trying to start something new is increasingly painful. At times, he says, the thought of it actually terrifies him. He is even suspicious of good ideas: “If you have a good idea for a poem, it isn’t one” he tells me laughing, before going on to explain that “if I know what I want to write about then I know it is bad because there is no surprise in it.” He believes in the reciprocity between his own experience in writing a poem and the reader’s experience in reading it. If he has not made himself feel –“if you don’t suffer, if you don’t feel, if you don’t surprise yourself” – in the process of composition, he believes there will be nothing in it for the reader.

But even as we discuss the difficulties of writing, something interesting happens to the way Paterson speaks. He is telling me how supposedly ideal circumstances for writing – on a writer’s retreat staring at a perfect landscape– are rarely conducive to his work. Instead he seeks out, counterintuitively, noisy places such as McDonalds: “Because then I have to carve the silence out of that… sort of make a cave.” There is something rather beautiful about the idea of a little cave of creative silence and the way he describes it, it feels in itself like a little bit of poetic refuge amidst the turmoil. Then, as he tells me how “feelings of excitement actually change the quality of the language that you use” he can’t help but describe the satisfaction of a poem when it “takes flight”. Even more affecting is when he compares when writing is going well to music, and how it can feel “that the poem is writing you, like when the [musical] instrument is playing you.” It is an apt metaphor for good reading too – those rare occasions when it feels like the poem is reading you. I am reminded of my first look at ‘The Eye’ in 40 Sonnets. It discusses

the self you slaughtered in the bliss

of her astonishing astonished kiss.

It is the kind of poem to stumble across, as I did, on the bus, and say to yourself, yes I know that feeling. Yet when you try to explain it to someone else you are left floundering, sending you straight back to the poem itself. I put this to Paterson. “I mean that is what you’re going for really. The whole point about writing a poem is to say that which hasn’t been said before.”

When looking over Paterson’s recent career, from editing 101 Sonnets in  1999, to his own version of Rilke’s Orpheus in 2007 to Reading Shakespeare’s Sonnets in 2012, and 40 Sonnets last year, it seems Paterson has found a form to do this. As Paterson says in the introduction to 101 Sonnets, the arguments about the rules and the “is it a sonnet debate?” rage on, but what actually is it about the form that appeals? “A sonnet fits a certain turn of human thought really well. Especially when you have got two things and you think there might be some synthesis that will resolve them into one.” Paterson describes the form almost like problem solving. They allow, he says, a way of putting two new things together and seeing what happens. Or a way of putting something in a new context and seeing what happens. Or a way of working stuff out. He continues: “It is a key motif among humans – repetition and variation. We need both. The sonnets do that wonderful symmetrical thing because they’re just wee, square poems at the end of the day. But they also have that thing that we like every time we see symmetry, which is we always put in an asymmetric break somewhere – a fracture- just to keep it interesting.” I start to get a glimpse not only of what he finds interesting about sonnets, but what Paterson is looking for in poetry in general. Something might be superficially pleasing, but that is not enough. By ‘breaking’ an idea, putting it to the test, struggling with it, he can find out if it stands up to interrogation and is therefore ‘worth’ knowing.

1999, to his own version of Rilke’s Orpheus in 2007 to Reading Shakespeare’s Sonnets in 2012, and 40 Sonnets last year, it seems Paterson has found a form to do this. As Paterson says in the introduction to 101 Sonnets, the arguments about the rules and the “is it a sonnet debate?” rage on, but what actually is it about the form that appeals? “A sonnet fits a certain turn of human thought really well. Especially when you have got two things and you think there might be some synthesis that will resolve them into one.” Paterson describes the form almost like problem solving. They allow, he says, a way of putting two new things together and seeing what happens. Or a way of putting something in a new context and seeing what happens. Or a way of working stuff out. He continues: “It is a key motif among humans – repetition and variation. We need both. The sonnets do that wonderful symmetrical thing because they’re just wee, square poems at the end of the day. But they also have that thing that we like every time we see symmetry, which is we always put in an asymmetric break somewhere – a fracture- just to keep it interesting.” I start to get a glimpse not only of what he finds interesting about sonnets, but what Paterson is looking for in poetry in general. Something might be superficially pleasing, but that is not enough. By ‘breaking’ an idea, putting it to the test, struggling with it, he can find out if it stands up to interrogation and is therefore ‘worth’ knowing.

Paterson’s knowledge of his craft is self-evident, and his next book, coming out in 2017, is a large academic work on prosody. Characteristically he describes it as “unreadable” but he goes on to say that he plans to draw two more approachable, reader-friendly texts out of the bigger work. I ask him how he approaches teaching poetry. His response is to describe to me the unexpected, and very grounded advice he gives to students: “if you are trying to write in metre then speak it in the pub for the night. You have to be able to speak iambic pentameter before you can write it. You don’t want to be sitting writing d-da-d-da-d-da-d-da-d-da. But if you sit in the boozer for the night then you’ll get it together.”

Paterson insists that writing poetry can never be a ‘job’ as such – and speaking in metre in the pub sounds anything but workmanlike – but to be good clearly requires hard work, rigour and the cultivation of certain instincts. Yet, while he did make a conscious decision to write his own collection of sonnets on the back of his other works in the field, it was not simply a matter of one thing leading to another. He talks about how Shakespeare would have studied Sidney’s sonnets and how Rilke made a translation of Michaelangelo’s sonnets before writing his own, but “sometimes you’re not always aware that you are making these preparatories… just like sitting and playing arpeggios. You’re trying to practise it into a motor skill, so you don’t have to be thinking about it.” This description of an internalising of the process agrees with something else he says about how his writing practice has changed over the years. I mention to him that I read that he writes around twenty poems a year. The truth, he says, is more like between six and eight. He laughs: “I don’t know when I thought I was writing twenty a year. Maybe at the start because a lot of them were duffers… Before I could write half of them and abandon them. Now I sort of think directly into the bin!” This idea conjures another image, that of the poet sitting at his desk, staring into space while imaginary bits of paper are screwed up and thrown into imaginary bins. It is an appealing, if slightly melancholy, analogy for what time and study and repeated trial and error bring: instinct. “I usually don’t know what it is I want to write about beyond a couple of images or a few words or a vague hunch. That’s when I know I’ve got something. This provokes another flight of fancy in me: the poet as bloodhound, restless, anxious even; then he catches the scent.

While I am in the business of stretching metaphors, permit me another. Listening back to a recording of our conversation I was struck by something. Each time we talk about writing, the idea of struggle looms large. Then, each time we talk about that struggle, little moments of poetry –an image or a phrase – seem to happen, only for us to plunge back into the struggle once again. I have an uneasy sense that I have been participating in something not unlike how Paterson describes the sonnet: repetition, fracture, repetition, fracture. Easy ideas are there to be tested and just when you think you might have an ‘answer’, it slips through your fingers. I joke more than once about making writing sound like torture. It gets Paterson animated: “I think that’s good! I think you should feel inadequate to the task. As a poet your whole arena is the failure of language and trying to do things to make language adequate.”

So, what we are left with is feeling. And while the idea of struggle punctuated by moments of magic describes for us part of what it means to write poetry, even when you take into account in-depth knowledge and the cultivation of instinct, it does not feel like we are seeing everything. Paterson tries again, describing the good moments of writing as like being taken over by “other forces”, but that almost suggests he doesn’t have anything to do with it. And then it happens.

It comes out of a question that I sometimes ask secondary school students at the start of a workshop. To be honest, I feel a bit cheeky putting it to Paterson. What does he wish he could do better in his writing? He starts off talking about never being complacent. This leads to him discussing what he envies in other writers. He wishes he had Heaney’s ear, for instance. He wishes he had Rilke’s insight into the nature of being. Then he enthuses about the writing process of Elizabeth Bishop, and how she would take a poem that was finished bar a word or two and would stick it on a cork board for ten years until she got it absolutely right. And something clicks. Just when it seems we might start talking about struggle all over again, Paterson provides a more revealing version of what writing poetry might be:

“There is no hurry for this stuff. The only thing is to get it right. Very often the difference between the great line, the really great line, and the pretty good line is almost nothing. Half a word… a little spin here … a little bit of context there…getting the whole thing to sound right in a way that is both musical and semantically original… If you just sit there and listen for long enough… I almost think that the whole thing is like safe breaking. You just try a wee turn on one word, and then another word, and then one word is going that way and then you hear a click… The whole line goes open on you… and the effect is transformative.”

It is transformative. It will sound like poetic license on my part, but in that moment a stillness descends on the professor’s office. It feels like all the wrestling with what it means to write well has been building up to this moment. One of his key tips for good writing is patience. This, it seems to me, is what we have been waiting for. After the silence, Paterson adds, a tiny bit sheepishly: “You do have to love it though. If I didn’t love it, I wouldn’t have the patience. So I must love it. I just don’t want to… meh!” For a moment he seems like he is going to embark on a discussion of why he struggles to say that he loves poetry. Then he stops. Language, for the moment, fails him. That topic is something to be wrestled with another time. In a sonnet, perhaps?

Stephen Carruthers

I would like to thank Don himself for his good humour as well as for kindly giving up his time. Many thanks to Peggy Hughes of Literary Dundee for all her help in setting up this interview.

Ed – A DURA review of Don Paterson’s 40 Sonnets can be read HERE.

Hello! I loved every bit of this article that the image of the two of you in his office engaged in an immersive and surreal way popped up right away.

As a fan who is working on Paterson, I am grateful for the insightful content. Having a conversation with him is one of my scholastic dreams 😀

Thank you!