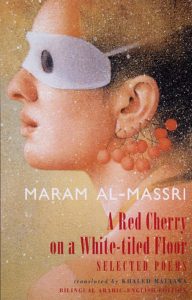

A Red Cherry on a White-tiled Floor: Selected Poems

Women like me do not know how to speak. A word remains in their throats like a thorn they choose to swallow. Choose to swallow.

In this first translation of her work into English, Syrian-born poet Maram Al-Massri confesses her secrets to us. Al-Massri is a woman stuck. Stuck between Arab tradition and modern femininity. Stuck in a failing marriage, simultaneously feeling desperate for the normality of family life and feeling desperately, dispassionately bored by it.

In this first translation of her work into English, Syrian-born poet Maram Al-Massri confesses her secrets to us. Al-Massri is a woman stuck. Stuck between Arab tradition and modern femininity. Stuck in a failing marriage, simultaneously feeling desperate for the normality of family life and feeling desperately, dispassionately bored by it.

These poems are filled with feelings of abandonment, a real abandonment thanks to her cheating husband, yet she confides in us that she too is a cheat – that she was never really happy in the first place.

Help me my kind husband, to close this port-hole that has opened on the highest wall of my chest. Stop me, my wise husband, from climbing the high-heels of my femininity for there at the crossroads a young man awaits me.

In this bilingual edition, the translated poems are laid out side by side with the Arabic originals. Al-Massri is caught between a traditional, arguably submissive womanhood and a modern, more sexually-open, feminist culture. She wants lust for her own sake, yet she still values the “status” of being sexually desired.

This confusion, the push-pull between her different ideals of womanhood, is the collection’s basis. The poet admits to her internalised gender stereotyping as she evolves from her traditional view of “femininity” into something more “male”. Aggressive, determined and sexually freer. A hunter.

He is moaning in pain, a deer breathing his last. How many bullets are left? How much mercy?

Motifs of this kind are sprinkled throughout, a red cherry on the white- tiled floor itself representing a woman of colour adrift in a predominantly white culture. The tiny fruit not only represents her sexual frustration, but perhaps more significantly and poignantly, reveals the shame she feels at its mercy.

Bearing that in mind, let me reiterate that Al- Massri chose to swallow her words.

Give me your lies. I will wash them and tuck them in the innocence of my heart to make them facts.

Despite her anger she still plays the part of the “good woman”. She satirises her own conflicting desires by whispering her true feelings to her readers. She plays us her fantasies in which she assumes a traditionally masculine role. She wants control.

She said: Yes I devoured him… I was hungry like a man… And like a man I splayed him across my desires blossoming with masculinity.

As the collection comes to a close, Al-Massri should be happier than ever. She has found love again; she is a mother: yet even now these things do not live up to her expectations. She still feels like a trapped animal. And she is so shamefully bored.

Old clothes fill her wardrobe, and children come in the evening with a loud din and low test scores. A husband who abandoned her, and a lover who no longer has the time.

Al-Massri knows her self-obsessed longings are tiring. She uses the reader as a conduit for her own self-loathing. She should be happy but she still has something inside – A Red Cherry on a White-tiled Floor– that feels as if nothing, not wife-hood, not mistress-hood, not mother- hood, is enough.

In one of the final poems, even sleep has now abandoned her. She calls the enveloping darkness “a new lover” – therein lies her problem.

Anything can be a lover to someone who is desperate for love. Everything feels like abandonment to someone who always plays the victim. It’s hard at times not to become exasperated with the poet as we watch her repeat the same mistakes. The genius is, Al-Massri understands this and still defiantly, maddeningly, displays to us her guiltiest, most honest parts. In so doing I can only hope she finally achieves her freedom.

Do not swallow your words, Al-Massri.

Becca Wilson

Very well written review…impressive…