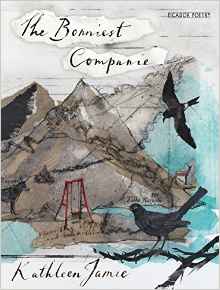

The Bonniest Companie

And the wild ways we think we walk

Just bring us here again.

In her latest poetry collection, The Bonniest Companie, Kathleen Jamie considers not only the Scotland of today, but the Scotland of the past, of her childhood and its timeless myth-shrouded wilderness. The poet presents the natural and political landscapes of her native land mingled with personal tales and memories.

Jamie “resolved to write a poem a week” over the course of 2014, the year of the Independence Referendum, and in doing so has created a time capsule – preserving that significant and turbulent time in Scottish history. Comprised of short, free verse poems, the book is separated into four sections in keeping with the seasons: “Merle”, “The Bonniest Companie”, “Migratory” and “Homespun”.

My opening quote is taken from the poem “The Tradition” which really captures the struggle for independence. Rebellion and national pride are hard to reconcile forces. With three pieces entitled “Migratory”, and a dissimulation of different birds on its cover illustration and within its pages, it is near impossible not to acknowledge the desire for departure in The Bonniest Companie. Whether this indicates just a personal wish to take flight or a national one, undoubtedly it points to the big question which consumed Scotland in 2014: should we stay or should we go?

Written days after the vote, the Independence Referendum is the subject matter of Jamie’s “23/9/14”, which focuses on the aftermath, and reflects the sense of defeat felt within the Yes campaign:

So here we are,

dingit doon and weary,

happed in tattered hopes[.]

The use of the Scottish vernacular, a particularly cherished trait throughout the entire collection, takes on new life here. The Scots is more pronounced in this poem than in others, giving it an air of defiance, as though even the language itself is determined still to establish the writing as independently Scottish. A similar idea can be found in the nostalgic piece “World Tree”. In this poem we are met with recollections of childhood which centre on a tree that functions as an anchor of memory. Here the poet considers what species it may have been, musing whether it was “elder or hawthorn, bour or may”. This is a curious line to include since “bour” and “may” are the Scots equivalents of elder and hawthorn respectively. The repetition is seemingly redundant. Yet there is great significance in having both versions included, given the political climate. Again we have a poem which just nudges the reader to consider the nature of what it is to be Scottish. The use of the political is subtle, cleverly woven into pieces as though to avoid overshadowing the charms of the natural world.

This collection is full of contemplations on Scotland’s physical landscape and animal inhabitants such as in “The Hinds”. Here we get a taste of Scottish mysticism and magic as deer frolic, beckoning you to join:

Come to me,

You’ll be happy, but never go home.

There is a sense of wonder and awe permeating the “dream-tinged land” of Jamie’s Scotland. The work is steeped in sentiment. I can’t help but feel nostalgic when reading certain poems such as “Another You”, which reflects so much of my own childhood. It catches in my throat.

The need to break free, to defy, to strike out on your own and find a place in the world is something which everyone experiences at some point. Yet, often when we take a leap into the unknown, we also look back to reflect on the past, “bring[ing] us here again”. There is movement and diversity unified through one year, land and perspective. By entwining myth, memory and reality, Jamie has compiled a stunning collection to capture not only the imagination but the heart in words that resonate long after 2014.

Larissa Woods

Leave a Reply