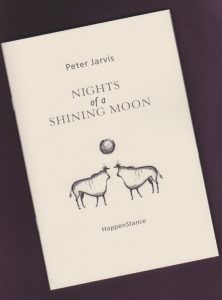

Nights of a Shining Moon

Proudly they stroll in absorbed dignity

towards bothlabatsatsi where the sky lightens

as if the handsome baratani are drawing up the new day.

Peter Jarvis’ first poetry collection, Nights of a Shining Moon opens at dawn in “Aubade”, with a hopeful image of two lovers walking into the sunrise, the persona watching them and listening to the crowing of the mekoko or cockerels. The inclusion of Setswana words mixed with English brings to mind Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, in which the English is similarly interspersed with Igbo. Rather than the use of foreign words being alienating, Jarvis in an interview with Poetry Spotlight remarks that his goal is to create a language “hybrid” in his poetry; he wishes to draw the reader close, rather than distance them. “Aubade” is as warm and inviting a beginning as the sunrise itself, with the meanings of most of the Setswana words made clear in context (a glossary end of the pamphlet supplements). It opens a collection which celebrates and yearns for Africa, its wildlife, its peoples and their cultures.

But, even in “Aubade”, it is the moon and the night that this collection truly addresses. In the next poem, “A San Triptych” – another piece which blends together beautifully Western poetic tradition with African, and in this case specifically San, culture – the moon is presented as a mysterious and multifaceted force. As we witness in three parts different aspects of San village life, we see the moon is able to give life, to the detriment of the San hunters:

On such nights the moon –

If you look up – is not kind…

If the slender springbok

Even twitches with life,

Then the water of the moon

Will make it start up.

The moon, the wind and other natural forces become powerful beings, connected to death and the cycle of time – two major themes throughout. Consider how an elderly tribeswoman prays to the moon for the gift of rejuvenation:

Then gift me instead your own [face]

So when I have died

I shall, brightly living, return.

The strong presence of night and the moon highlights the sense of mystery and uncertainty in these poems, and hints at an underlying darkness. While poems like “Ngezi” celebrate the continent’s wildlife and natural beauty with the almost whimsical scene of two figures “dawdling downriver”, with a baby crocodile as their unusual companion, others are more unsettling: “The Green Verandah” starts with a speaker nostalgic for old stories, but ends with a tale of sickness and animal death, and unanswered questions. “The Wrong Tree” lays this darkness bare, diving into the not-too-distant history of atrocities committed against the indigenous people in South Africa. In this instance we learn of a boy caught in the crossfire of the war for Namibian independence, written with grisly and heart-wrenching detail.

Returning to the opening poem, one already sees the threads of uncertainty Jarvis interweaves with those of celebration throughout the whole, haunting collection. The aubade form is traditionally a poem or song associated not only with lovers, and daybreak, but specifically with the separation of lovers at daybreak. This lends a note of poignancy to the poem, and makes one wonder if the strolling baratani walk so slowly now only to prolong their parting. Were they not perhaps happier under the moon, and the “dinaledi phatsima”, united against the cold, mysterious night which maybe also granted them the time to come together in the hours of darkness?

Anna Durkin

Leave a Reply