Brother

Perhaps we all long for a more carefree period in our lives. Nostalgia for childhood is almost universal; however, this outwardly innocent melancholy is ultimately dangerous as by its very nature nostalgia romanticises and we forget the past’s real darkness. In Brother, award-winning American poets Matthew and Michael Dickman’s latest collaborative collection, the sibling poets reminisce about their childhood but a sinister and unsettling cloud looms. How happy in truth are these memories? If this collection appears a rather disconcerting read, there is good reason. These poems are the Dickman brothers’ tribute to their older brother Darin who committed suicide a decade ago.

Perhaps we all long for a more carefree period in our lives. Nostalgia for childhood is almost universal; however, this outwardly innocent melancholy is ultimately dangerous as by its very nature nostalgia romanticises and we forget the past’s real darkness. In Brother, award-winning American poets Matthew and Michael Dickman’s latest collaborative collection, the sibling poets reminisce about their childhood but a sinister and unsettling cloud looms. How happy in truth are these memories? If this collection appears a rather disconcerting read, there is good reason. These poems are the Dickman brothers’ tribute to their older brother Darin who committed suicide a decade ago.

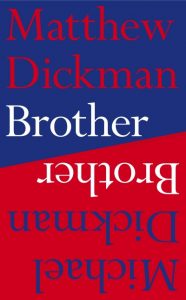

Offering a refreshing advance from their first collection, 50 American Plays, Brother is in two halves. One half reads as a conventional printed text but to carry after mid-point, you would need to turn the whole book upside down to read the second part. Brother can be opened with Matthew’s poetry starting the collection, with his brother’s poems forming the counterpart, or flipped with Michael’s work coming first. Accordingly, there are two content pages; the front cover might also function as the back cover and vice versa.

Michael’s half of the collection is fragmented and highly imaginative, creating a dreamy atmosphere with a childlike quality. Here, the signature style Michael has been developing since his first collection in 2009 makes the undertones of death in his poetry even darker. In one of this collection’s first poems, “Kings”, Michael lulls us into a story about himself as a child at play pretending to be a king. That would be a sentimentally pleasant poem without lines such as, “What a motherfucker that is[.]” Michael disorientates the reader by continually adding hostile words to childlike fantasies. The fragmented structure of his poetry emphasises these violent images – physically broken off and centred on the page.

The poetry in Brother which arguably evokes the most emotion is framed in simply-worded stanzas, which are that are not just unsettling in their capacity to shock, but in how they are quietly able to convey small aspects of grief:

I will look

more and more like him

until I’m older

than he is[.] (“Killing Flies”)

Here, Michael starts to show the reader the harsh truth. It’s dramatic, heart-breaking and subtly realised. This stanza fully illustrates their older brother frozen in time while the surviving brothers grow older without him, echoing something of Laurence Binyon’s familiar words in “For the Fallen”. This collection is not about preserving some saccharine childhood but it focuses on the misery of a childhood fossilised and denied its natural outcome.

Unlike Michael’s section, Matthew in the first part captures this meaning immediately, writing more straightforwardly, contrasting the fragmented quality of his brother’s verses. Like his brother, Matthew intermingles the imagination of childhood with an intense, violent imagery designed to unsettle. In one of his opening poems, “Trouble”, he tells the reader about his brother’s death, sharply, in the middle of a stanza:

…My brother opened

thirteen fentanyl patches and stuck them on his body

until it wasn’t his body anymore. I like

the way geese sound above the river. I like

the little soaps you find in hotel bathrooms because they’re beautiful.

Here the grief and violence associated with his brother’s suicide is interspersed with a childish wonderment, highlighted by the two line breaks on “I like.”

Although both brothers offer different poetic styles, they are unified by the tragedy and its emotional legacy. Each poem in the collection is a heartfelt entry to shared feelings of grief framed in especially unsettling child-like fashion. In utilising a very adult morbidity overlaid on images of childhood, the Dickman brothers have achieved their poetic goal in a format that interlocks creatively, showing both their differences and their unity in the face of sadness.

Dervla McCormick

Leave a Reply