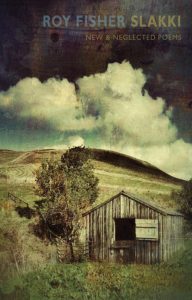

Slakki: New & Neglected Poems

Roy Fisher’s latest collection, Slakki: New & Neglected Poems, epitomizes the poet’s struggle to stabilize his “everyday self — a quite presentable, penurious, and apparently unambitious young man” in his poetry. The process of putting together the collection addresses the creation of a poetic identity, the representation of Fisher the writer.

Roy Fisher’s latest collection, Slakki: New & Neglected Poems, epitomizes the poet’s struggle to stabilize his “everyday self — a quite presentable, penurious, and apparently unambitious young man” in his poetry. The process of putting together the collection addresses the creation of a poetic identity, the representation of Fisher the writer.

Fisher’s collection is a compilation of poems composed over the decades from 1951-2014, printed in reverse chronological order. Is this an intentional juxtaposition? Does the author reckon that the previously unpublished pieces are the ones with the most integrity? Are they the ones potentially untainted by the influence of publishers, and free from the awareness of writing for an audience? Or, is Fisher instead asking that his readers uncover his identity from the outward in, poem by layered-poem? Built upon each other, but here, unraveled backwards. Either way, Slakki is a beautiful rendition of the soul striving for complete, artistic integrity.

Roy Fisher “works” with words. One of his poems metaphorically addresses this skill.

1. working water held captive for a while then sluiced away to join the world’s other waters again.

Words are fluid like water. They flow in and amongst a plethora of definitions, imposed upon by ever-changing cultures and languages. Here, Fisher reiterates the theme that his poems, in a sense captive to time, were neglected for a while until he recently assembled them together again to join the rest of his published work.

The collection commences with “Signs and Signals,” commemorating World War One. Fisher introduces himself to us through direct language; he writes: “the trench wall came away without warning and exposed the singularly tall German officer.” The exposure detailed here reflects the intention of the collection, and completely reveals the poet’s art in its complex, stripped-down entirety. The stanza finishes, “It would be the most splendid figure of a man he’d ever see.” At the core, Roy Fisher’s sincerity in Slakki is not only evident, but also executed with refined rhythm.

Fisher’s poems are like the patch in “A Garden Leaving Home,” “planted saplings at random to develop [a] presence of little wood — rowan, field maple, hazel, goat willow, crab, walnut, sloe.” His monologues, memories, memorials had “become his little wood.” In “Bench,” a poem for Peter Robinson, Fisher writes, “Apply Time.” The second section continues: “With my time in my eye.” Readers are left to question: is Fisher implying that poetry, like wine, matures if neglected over time? “A Number of Escapes and Ways Through” reads: “I created everything I see. It wasn’t hard.” Despite the fact that Slakki: New & Neglected Poems often focuses on the concrete, Fisher’s poems are philosophical, thought-provoked. He sees the abstract and creates a visual for us.

In the afterword, Fisher admits that “required to bear weight, [his poems] would shift stance.” Fisher’s most admirable accomplishment may in fact be the way he accepts imbalance; he wittily proves that instability is not insufficiency. Slakki has a certain charm. Through its poems, we, as readers and reviewers, recognize our own, similar efforts to solidify our ever-evolving identities. Uniformed in style, Roy Fisher’s collection engages a sundry of poetic phraseology. In “While There’s Still Time,” he promises: “Make no mistake: my voice will be heard once again, and as never before.” As we read Slakki, we recognise our own voice in his various interpretations. Fisher’s tone may be unstable, but his work is undeniably, and quite sufficiently, supported by his ability to interest his readers.

Shanley McConnell

1951 to 2014 is not two decades, it’s 63 years! ‘Apply time’!

Well spotted, and have amended. Thanks! – Ed