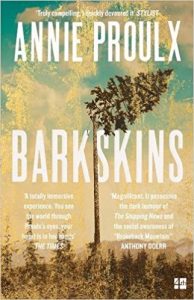

Barkskins (LONGLISTED, 2017 BAILEYS WOMEN’S PRIZE)

Barkskins: a simple title for a book which is vast in scope and ambition. Pulitzer Prize-winner Annie Proulx of course has a distinguished background in considering North America’s growing pains protracted over centuries, cultures and evolving politics. She is well able to recognise which grafts take and which do not. So who better to tackle Barkskins ‒ this epic tale of two families, growing differently through the fate of the continent’s forests, from 1693 to 2013?

Barkskins: a simple title for a book which is vast in scope and ambition. Pulitzer Prize-winner Annie Proulx of course has a distinguished background in considering North America’s growing pains protracted over centuries, cultures and evolving politics. She is well able to recognise which grafts take and which do not. So who better to tackle Barkskins ‒ this epic tale of two families, growing differently through the fate of the continent’s forests, from 1693 to 2013?

Proulx traces the descendants of two Frenchmen, initially paired under a logging seigneur: the imperious Duquet (later anglicised to Duke), and the thoughtful Sel. The latter’s family tree grows from his happy marriage to a Mi’kmaw woman. So already, nominally a haughty foreign duke, perhaps and yes, the salt of the earth seed clues as to how their respective lineages will contribute and flourish. The book is riddled with such punning names, and for my tastes, correspondingly simplified characters – consider Flense the cutting lawyer, the straight-talking German Breitsprechers and more. Similarly the Native American voices have more than a whiff of Hollywood Westerns in the stilted rendering of their speech.

The narrative addresses the wrongs visited on those vast lands by colonial settlers, their culturally and environmentally disastrous behaviours, not only in America but in Europe, South America, then Africa, the glaciers of Greenland and to China and Oceania. Indeed, the entire world’s future is examined. These issues should be written, and the writer’s opening dedication asserting her “lifelong interest in historical change and shifting disparate views of past and present” is laudable and manifest, but as a huge admirer of her work I found significant knots in Barkskins.

Arguably, any moral cause a writer holds precious is dangerous cargo. If there is a pressing need to educate, to hammer home a point at any cost, there may indeed be a considerable cost to the writing. That old adage “show, don’t tell” is buried quickly. On page 30:

Monsieur Trépagny exploded. Eels were savages’ food, he said, and he expected something better as befitted a seigneur. They were witnessing Monsieur Trépagny’s transformation into a gentleman manifested by his new garments and his dislike for eels, which in the past he had always relished.

Later…

Although Duquet et Fils had no hesitation in cutting big trees wherever they grew, it was intolerable to be the victims of that practice.

Quite. So, at very regular intervals Proulx takes pains to show, and then feels obliged to tell. She has either lost faith in her narrative or her reader. This grieves me greatly, and although that tendency lessens somewhere about the 500th page, once so regularly undermined, this reader at least found it hard to shake off the perceived insult. There is a somewhat punitive way with backstory, with business accounts and conveniently explanatory “conversations”. In the final 150 or so pages, I had the strong sense that Proulx too was tiring of her tale and was rather desperate to wrap things quickly, adding in the last of those marvellously gory and suitably-arboreal deaths. (Proulx likes an apt fate, here presumably at the hands of the maligned tree spirits). Alas, too often the veneered characters were insufficient to induce any real care in this reader.

Proulx can write gloriously and hauntingly, and has ample published proof. Anyone choosing to read a hardback Proulx running to 700 plus pages is unlikely to be completely naive about colonialism’s evils or the environmental catastrophe of deforestation. That reader is likely alive to the possibilities of a creatively fragmented narrative, using say interspersed balance sheets, letters and indigenous peoples’ messages to challenging effect.

The jacket asserts “Barkskins is her greatest novel”, but I sense she has selected a machete to carve a casket. Those wishing to read how the prodigiously talented Proulx writes a huge American fusion of history, fiction and contemporary consequences should turn to The Shipping News or Accordion Crimes.

Leave a Reply