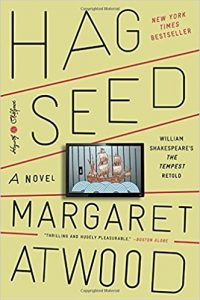

Hag-seed (LONGLISTED, 2017 BAILEYS WOMEN’S PRIZE)

Hag-Seed : The Tempest Retold is part of the Hogarth series of re-workings of Shakespeare by “acclaimed and bestselling novelists of today” (p. 295), and of course there will be readers who cannot think why such a thing is necessary. But that is a nettle to be grasped another day.

Hag-Seed : The Tempest Retold is part of the Hogarth series of re-workings of Shakespeare by “acclaimed and bestselling novelists of today” (p. 295), and of course there will be readers who cannot think why such a thing is necessary. But that is a nettle to be grasped another day.

In Atwood’s story, actor-director Felix has been ousted from his cushy job at the Wakeshiweg Festival by the ambitious Tony, shortly after the traumatic death of Felix’s three-year-old daughter Miranda. The book covers the twelve years that follow, in which Felix goes into self-imposed exile in a hovel in the woods, and eventually works through to a form of redemption.

It is clear that the reader’s sympathies should be with Felix, who is suffering. But what struck me is just how hard Atwood works to keep us from engaging with the main character. The frequent leaps of time, though carefully signposted, stopped me from entering into his world for longer than short bursts. The occasional imposition of present tense had the same effect, jerking me out of the flow of the story. The ways Atwood used Shakespeare’s story also kept intruding, so that I found myself pausing to think, “Oh, that’s clever” or “Oh, I see what she’s doing there.”

Still, Felix’s point of view is overwhelmingly central. He is surrounded by two-dimensional characters, which is how he sees others. The relentless dreariness of his life has a certain mesmerizing quality, which is how he half-perceives and half-creates it. But in spite of that, it was impossible for me to believe in Felix’s view of himself as a misunderstood genius. Atwood seemed to want me to feel he was just a poser, with his Shakespearian vampires, his penchant for glitter confetti, his transvestites on stilts.

Spending time with Felix was proving to be a bit of a penance…

And then he started teaching Shakespeare to the inmates at Fletcher Prison, and I was immediately ready to forgive all (one of the themes of the play). Felix is a strong, inventive, inspiring teacher. The chapters in which he half-leads, half-follows the inmates into their understanding of the play are why I grew to love this book. He produces bits of pedagogic magic which I will be making use of (properly accredited) in my own teaching. For example, he bans regular swearing and only allows curses from the play. He assigns the task of creating an after-story for each of the play’s main characters. He is flexible and firm.

Other reviews have praised Atwood’s humour in Hag-Seed, and although Felix himself is about as funny as a hearse, the Fletcher prisoners – the rude mechanicals, perhaps – are hilarious. Their rap versions of various scenes from the play are witty and funny – not always the same thing. With their costume designs, their interpretation of Ariel as a blue alien from outer space, the rap and dance troop of Caliban and the Hag-Seeds, they achieve what Felix’s professional pomposities never could. And yet, they admire Felix, and my opinion of him as nothing more than a talentless ego was changed by them. As Felix points out, changing your mind is also a theme in the play.

In the end, Atwood achieves a conclusion to Hag-Seed which satisfies and uplifts. It is built out of Shakespeare’s own ending for his play. But does it arise naturally out of the character of Felix the reader has spent all this time with? Not really. A Felix who is content to hand over control, his ego adequately fed, with all of the rage and despair and desire for revenge that have shaped the last twelve years of his life turned off as if by a switch, does not ring true. But Prospero’s words from The Tempest‘s Epilogue are enough to excuse all: “Let your indulgence set me free.”

Leave a Reply