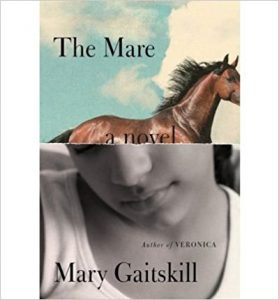

THE MARE (LONGLISTED, 2017 BAILEYS WOMEN’S PRIZE)

“Feeling by themselves ain’t what matters.”

“Feeling by themselves ain’t what matters.”

The Mare, Mary Gaitskill.

Think of a girl called Velvet, a dangerous horse, a riding competition, a growing obsession; the elements of one of the most-loved children’s films in the world. Mary Gaitskill’s “The Mare” draws freely and openly on the stories of National Velvet and Black Beauty, but sees the world not through the eyes of the horse, but through the eyes of the main characters. In the form of very short chapters, this polyphonic narrative is set in downtown and upstate New York in the Obama era. Gaitskill’s Velvet is Velveteen Vargas, a socially deprived girl from the black community of New York City. Chosen to take part in the Fresh Air for Kids scheme, she finds herself spending time at the country home of Ginger, a forty-something recovering alcoholic and her teacher husband, Paul.

The Mare is not only a fascinating animal story – horse-lovers will be delighted by Gaitskill’s skill and insight in describing horse behaviour and the growing love between an unprepossessing equine reject and a young girl from another world, herself a sort of reject – it is equally a subtly complex examination of the profound problems of communication and understanding between social classes and cultures. The themes of bullying between children and between adults, animal ill-treatment, violence, and inexplicable love run in a broad stream beneath the narrative. Silvia Vargas, Velvet’s angry, illiterate mother is deeply suspicious of Ginger, whom she imagines to be a vastly wealthy woman who will bring about her daughter’s death by allowing her to ride horses. Their only communication is by phone, via an incompetent interpreter – Silvia speaks no English – their conversations consisting mainly of Silvia’s screaming abuse at the unknown woman who is becoming too fond of Velvet. Gradually, after many upstate visits, Velvet becomes a courageous and competent rider, closely bonded with an unpredictable mare, whom she christens Fiery Girl. Velvet’s returns to her Brooklyn home are inevitably met with violence and screamed abuse from her mother.

The challenges of maintaining a character’s voice over the length of a novel and point of view are great, especially the changing voice of the developing black teenager. Sometimes even a writer with the skill and experience of Mary Gaitskill can just miss those subtle changes.

But Gaitskill’s characters have relationships as flawed as they are human. Ginger’s self-destructive and alcoholic past is bound up with a man she refers to only as Michael, with whom she explored the world of drugs and alcohol. Meeting up with him again at an AA meeting in New York, they go back to his apartment, where nothing very much happens. Why was Ginger attracted to Paul, apart from by the fact that they were both in recovery? As a teenager, Velvet falls in love with Dominic, a boy from her neighbourhood. He rejects her because he is about to become a father and believes he is doing the honourable thing by supporting the mother of his child. Why does the habitually hostile Edie, Paul’s daughter from a previous marriage, want to be friendly with Velvet? Why is Velvet so determined to ride Fiery Girl, when no one else is allowed into her stable?

Stressed and superstitious, Silvia professes to hate her daughter and lays into her with her fists whenever she returns home from upstate Ginger’s place. And yet there is something deep and indestructible going on here and in all these unfathomable relationships. Velvet describes her mother’s illness: “ I stayed with her all night. She saw my clothes and make-up. I saw her look and felt it […] She yelled like always. But not about that.”

Their relationship does not need to be perfect for it to be valid, for it to be where they belong, any more than Ginger’s relationship with Paul, or Velvet’s with “her mare”, Fiery Girl. Isn’t this what the whole work is about?

SUSAN HAIGH

Leave a Reply