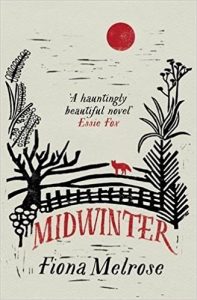

MIDWINTER (LONGLISTED, 2017 BAILEYS WOMEN’S PRIZE)

I might not have read this novel were it not longlisted for the 2017 Baileys Women’s Prize. The hardcover with its stylised Edward Bawden-like black and red linocut of a rural scene – red sun, red fox, and red blurb byline counterbalanced by the bold black lines of plant life – seemed, well, just a little too 1940s cosy retro. Yet Fiona Melrose’s debut novel is hardly bucolic, suffused as it is with a very modern concern about how we relate to the natural world and to one another.

Midwinter‘s plot is simple. The loss of wife and mother lingers on in the lives of father (Landyn) and son (Vale) despite the intervening years. Theirs is a troubled relationship marked by a spiral of grief, guilt, blame, resentment and suppressed hostility followed by bitter outbursts. These provoke an emotional rawness that mirrors the wintry conditions of these flat Suffolk farming plains. One ill-fated day, Vale and his best friend, Tom, take a boat out in stormy weather while drunk; their actions lead to similar life-changing consequences contained in Landyn’s story. How is one to deal with pain and guilt? In the case of Vale (and to a lesser extent Tom), Midwinter presents us with a very moving portrait of an inarticulate, emotionally bewildered young man who desperately needs to find a way to live.

These might be well-trodden and plotted paths, but Melrose brings a freshness to its telling, shuttling as it does between time present and times past, Suffolk and Zambia, and between the alternating first person voice of both father and son. The past is not made to divulge all its secrets at once: each narrative follows a slow rhythm of remembering, triggered by events in the present. In that way, the consequences of the past are dealt with without the reader knowing the whole picture, nor understanding its full tragic dimensions, till the novel’s cathartic end. Furthermore, each first-person voice carries the full force of mental anguish which, again, only the reader is privy to. In this, Midwinter‘s portraits of men, some strong and silent, some more angry and young, are twinned with the mute beasts of the fields.

If death and violence are part of that farming world (animals are, of course, farmed for food), survival in these conditions is to hold death in abeyance momentarily, and to be treated with decency and care for just a little while longer. As the pigs are selected and herded towards their slaughter, the farmer reminds his son about the need for a good death: “I like them to be treated right. I don’t want them cold and fearful and cut up. They’ve lived well and they should die well too.” Good farming husbandry also transfers to family: you bring your son up right, you love him, and then give him space to come round and live.

A sustained attentiveness to the land and the animals that thrive on it reveals a special kind of language beyond words, enabling the companionable co-existence of human and non-human. Muteness is not tantamount to emptiness. As Landyn remarks of a tree cut back to encourage growth, the history that surrounds that tree fills its silence with a dense companionability that allow both plant and human its place and time: “I felt encouraged by that old tree that day. It had history to it and healing. There was one like it on our old farm in Kabwe, local tree, I never knew its name but I knew its heart. You get those sorts, let you into their shade on a hot day. Let you sit deep and close.”

If the vixen that threads its way through the novel cannot bear the freight of its projected symbolism, Midwinter‘s feeling for the land and its inhabitants is nevertheless evocative, lyrical and sensitive, searching for transcendence with feet firmly planted on the earth. This feels more solid than an urbanite’s simple pastoral hymn.

Gail Low

Leave a Reply