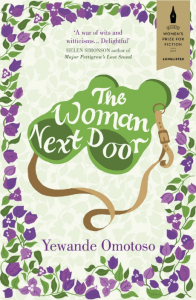

THE WOMAN NEXT DOOR (LONGLISTED, 2017 BAILEYS WOMEN’S PRIZE)

The Woman Next Door is Yewande Omotoso’s second novel, appearing five years after her debut Born Boy, which earned her the Etilasalat and Norman Mailer Fellowships and the Miles Morland Scholarship. Omotoso grew up in Nigeria and has lived in South Africa since 1992. The novel reveals the continuing prejudices in modern Cape Town suburbia through the lives of two neighbours, Marion Agostino and Hortensia James. The book dips in and out of present time to build a picture of the pasts of each of the women; both have had highly successful careers, but neither has found their marriages, nor their current situations, to be what their younger selves would have wished for.

The Woman Next Door is Yewande Omotoso’s second novel, appearing five years after her debut Born Boy, which earned her the Etilasalat and Norman Mailer Fellowships and the Miles Morland Scholarship. Omotoso grew up in Nigeria and has lived in South Africa since 1992. The novel reveals the continuing prejudices in modern Cape Town suburbia through the lives of two neighbours, Marion Agostino and Hortensia James. The book dips in and out of present time to build a picture of the pasts of each of the women; both have had highly successful careers, but neither has found their marriages, nor their current situations, to be what their younger selves would have wished for.

They are introduced to us in a slightly cold and unforgiving light from the beginning: Hortensia is presented in the opening chapter as someone who will go out for a walk, leaving her dying husband alone in the house, against the advice of the nurses, “- to get away from a dying man, to give him room to die faster,…”. Both women are nearing the end of their lives and as their histories and life stories are laid out for us, we discover that it is not just their colour (Hortensia is black and Marion is white) that has embittered each of them to their situations.

The women’s lives become entwined in the book as they begin to build together a shared story – a hostile relationship at times, as a result of being pushed together, but one which offers some hope. Hortensia and Marion are strong, highly opinionated and flawed characters, and this makes them difficult to warm to. However, through the gradual exposition of their histories, our sympathy grows for each of them. It is refreshing to read and listen to Hortensia and Marion’s own voices, and watch a relationship develop between female characters where they are not stereotypes, are not in their early years and not fulfilling some kind of mission.

The pace of the book is good, with a variety of locations (England, South Africa and Nigeria), and movement between the present and the past. Time is given to explore some of the stories that make up the past with detail given and a feeling of indulgence which is pleasant, with stories behind courtships and subsequent marriage pathways. However, the same cannot always be said for the stories of the women’s present, leaving that part of the book sometimes feeling a little empty.

There were a couple of things that jarred with The Woman Next Door. Firstly, towards the end, the story makes several shifts in direction that seem unnecessary and are dealt with superficially. These storylines are not fully explored and almost pushed out of the way, for example the relationship between Marion (white) and her sick, retired maid (black) who always wanted to teach but whose ambition Marion actively discouraged.

Secondly, the main plot circles around the women and all the contributing factors to their perspectives of each other and their developing relationship which lead to subplots that are so numerous that many are barely touched on. The Woman Next Door tries to cover multiple themes, but delivers depth to only a few – jealousy, infidelity, encroaching decrepitude and disappointment. Many others; racism, friendship, supremacy, marriage, rivalry, religion, chauvinism, regrets, restitution, apartheid and family are given a passing glance but not really handled satisfactorily.

Overall, the book is an enjoyable read. However, it presents a slightly depressing portrayal of old age with little cheer, and no satisfactory closure to many of the subplots and vignettes. Perhaps this was the author’s intention – to leave a realisation that life is not full of tidy stories that start and complete in time for the end of one’s life. Whilst this might indeed be so, for all its plus points, the book did leave me with some sense of dissatisfaction and incompleteness.

Nicola Innes

Leave a Reply